Filmed July 1968

My return to STAR TREK early in their third season found more changes. Producer John Meredyth Lucas was gone, replaced by Fred Freiberger. Director of photography Jerry Finnerman was still there but on his final assignments; the studio had released him from his contract, and he he was leaving the series to photograph a feature film. Paramount was still next door, even closer now because the wall that had separated the two studios, Paramount and Desilu (originally RKO Radio Pictures), had been torn down. I sensed a tense atmosphere in the company almost at once.

There were no locations required to film this episode. In fact the entire show would be filmed in the Enterprise set on Stage 9 except for one four page scene in a herbarium set on adjacent swing Stage 8. Casting was half easy. For the role of Larry Marvick, the tortured soul in love with Miranda, I wanted David Frankham. I had directed David twice before — first on the main stage of the Pasadena Playhouse in a production of Somerset Maugham’s THE CIRCLE and later in the episode THE TRAP on TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH. My request was greeted with approval. The other half, the role of Miranda, was more difficult. We checked out Jessica Walter, but she was not available. Other availabilities were checked with no success. Now STAR TREK had a standing rule that guest stars could not repeat unless they were coming back to play the same role. At this point I daringly suggested we bring back Diana Muldaur (who had guest starred the previous season in RETURN TO TOMORROW, about which the less said the better) and that we put her in a black wig. That suggestion was finally accepted.

Our first day of filming, Tuesday, July 16th, arrived, and I was greeted with a mutiny on the Enterprise. Bill Shatner and Leonard Nimoy had very strong objections to a portion of the scene we were scheduled to do that day and were refusing to film. Since the objection was to dialogue involving a piece of jewelry that Gene Roddenberry had designed, he was summoned to the set. (I have since learned that Leonard Nimoy first phoned producer Fred Freiberger to tell him of the problem. When Freiberger refused to take any action, Leonard called Roddenberry.) The morning was spent in a round table war with the six characters involved in the scene plus Gene and me. But the battle was strictly Bill and Leonard vs Gene. Bill and Leonard felt Gene was using the scene as a promotional commercial for a pin he had designed; the pin was part of Leonard’s costume. Gene vehemently denied these accusations, but the guys were adamant in their refusal to be a part of something they considered to be commercially oriented. The final result of the long morning’s angry combat was that Gene agreed to rewrite the scene. That meant it could not be filmed that day. The balance of work on that first day’s schedule was four short sequences (that totaled a page and a half) in the Enterprise corridor. I did not want my first day’s work to be limited to a page and a half of what I called “bread and butter” scenes, so I suggested we do a dramatic three page scene between Diana Muldaur and David Frankham. Which is what we did. I will discuss these scenes later as I reach them in the progress of our story.

The script was very positive in stating the ground rules for who should be allowed in the presence of the arriving Ambassador, and we were very careful that this exposition be presented clearly. So now let me take you to the Transporter Room and let the story begin.

I would have preferred filming the scene of Spock and Dr. Miranda Jones escorting the Ambassador to his quarters in a single dolly back two shot. But the corridor set was not long enough, so we filmed a dolly medium shot of Spock speaking to Dr. Jones (who was off camera) as he moved the length of the corridor. Since that was not sufficient to complete his dialogue, we then moved Spock and the camera back to the starting position and moving through the same stretch of corridor, we continued the scene. I’m not sure, but I think we may even have had to do a third run. We then did the same thing with Dr. Jones, filming her moving medium shot speaking to Spock, who was off camera. In the editing room by intercutting Spock and Dr. Jones we gave the illusion of the two of them moving through a longer corridor than the one that existed.

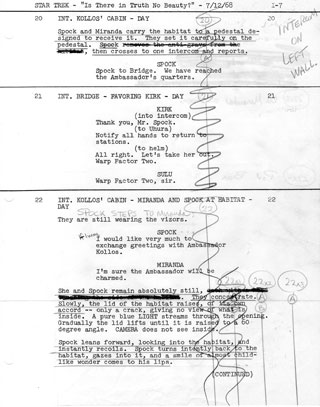

Things would happen on this episode in postproduction that I had not faced before. The script in Scene 22 again was very definite, this time describing Spock’s meeting the Ambassador.

And now the scene.

Due to ensuing circumstances that occurred after I turned in my director’s cut, I did not view the final master print until the night the show aired. When I saw this scene, I was appalled. Who had ordered the horror film flickering green light and the comic strip animation that was inserted to represent the ugliness of the Ambassador? I had my suspicions, since that kind of vulgarizing technique had never intruded into STAR TREK before. My objection was that its insertion negated the true intent of the scene, which was to show Spock’s reverent reaction to meeting the Ambassador, an esteemed person, not a monster. After Spock left, there was an even greater distortion. The script called for Miranda to look at the CLOSED receptacle as she said, “What is it he sees when he looks at you? I must know.” The unscripted addition of a shot of the receptacle opening with a repeat of the animation was outrageous and tasteless.

The portion of the dining scene that caused so much consternation that first day was rewritten by Gene Roddenberry. The business with the IDIC pin that Spock wears had been drastically trimmed so that all could dine (and act) at ease.

Again the script was very clear. Having established that Miranda had telepathic abilities, she was suddenly aware of the presence of thoughts of murder.

And now the scene.

Further reason for me to be distressed: the superimposition of the Ambassador’s receptacle was WRONG! Miranda was reading by her telepathic ability the thought of murder. Who in the group was thinking that thought? The Ambassador had no seat at that table!

I have always said, METAMORPHOSIS was my favorite of the STAR TREK episodes I directed. I felt there was a mysterious and poetic dimension to the science fiction. I saw some of that same element in this script. Jerry Finnerman certainly rose to that challenge in his photography. And the scene between Miranda and Larry that we substituted on the schedule that first day was a good example of why in my preparation, I liked to have more than just the intended day’s schedule prepared; and why I liked working with actors who were prepared when unexpectedly they were asked to do scenes that were not scheduled. Filming I found usually followed the lines of Murphy’s Law: If something can go wrong, it will.

Again the superimposition of the Ambassador’s receptacle is WRONG! Miranda’s next line was, “So it’s you. Who do you want to kill, Larry? Is it me?” The Ambassador at this point does not figure in the equation.

The next day at dailies, following this scene Bobby Justman was heard to remark, “I wonder how she’ll look in a red wig.”

I decided I wanted to use the fish-eye 9mm lens again, the lens Jerry Finnerman introduced me to on METAMORPHOSIS, but this time I wanted to use it differently. Before it was used to give a greater expanse to a very small area; this time I wanted it to be the distorted point of view of a mad man.

In a five hour taped interview in 2002, Jerry Finnerman said, “Directors of Photography create the mood of the show. They create the dimension. They tell a story with their lights.” That had been true in all of our STAR TREK collaborations, especially THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, METAMORPHOSIS and OBSESSION. And it was most emphatically true of his work on this episode.

IS THERE IN TRUTH NO BEAUTY? was the third time Diana Muldaur and I worked together; there would be two future collaborations. I think Dr. Miranda Jones was the most rewarding of our associations. I liked directing women, but the television industry of the sixties and seventies did not offer women the kind of roles that the movies had in the thirties and forties. Or the kind of roles that live television had provided in the fifties. Early sixties shows like DR. KILDARE, ROUTE 66, NAKED CITY, BEN CASEY had continued that trend, but by the seventies action had relegated women to secondary supporting assignments. That’s why STAR TREK was so unusual. Four of the seven STAR TREK’s I directed had strong leading roles for women. And it also had in Jerry Finnerman a director of photography who knew how to photograph women..

Gene Roddenberry, in his conception of the character of Spock, and Leonard Nimoy, in his total realization of that character, had boxed in an enormously versatile actor. Earlier in THIS SIDE OF PARADISE Spock was freed emotionally by the spores, and Leonard was able to use his talent far beyond the constraints of Spock’s character. The mind link was another route to that same freedom.

As I wrote, I was disturbed by the animation supposedly representing the Ambassador’s ugliness. I was grateful however that whoever made that erroneous decision was very inconsistent. How come when Spock opened the Ambassador’s vessel in this sequence, there was no animation? As you will now see it couldn’t have been because the Ambassador was no longer ugly.

Television too seldom allowed scenes that exploded emotionally. The excitement too often provided was generated by car chases and fights. But occasionally a script would provide that excitement by the conflict between the characters. You saw it earlier in the death of Larry Marvick. Now Kirk and Miranda go at it.

I have to confess, I’m getting bored with the repetition of this topic. Why the animation?

Finally the last scene of the film. Was it possible there would be no further reasons to cause me anguish? What could possibly be done in postproduction to a simple scene in the Transporter Room?

Did you catch the gross error? The script and my director’s cut had Kirk say, “Peace”, and then he exited. Who decided to have him hang around, without a visor, which wouldn’t have protected him anyway because he was human? I have run out of scorn!

I think friendships in show business are different than in any other profession. Very close ones can evolve in a very short period of time. But the profession also separates people who have become friends and for long periods of time. I have found that when reunions occur, the friendships pick up right where they left off. David Frankham and I first met and worked together 50 years ago. I had not seen him for 22 years when he recently came to visit. And as I said, the bonds of friendship did not recognize that long period of separation. While he visited, we watched IS THERE IN TRUTH NO BEAUTY? on a big screen. Photographs were taken of David viewing his performance.

The second photograph to me is very surreal. David is looking at his performance on the screen. But Larry Marvik seems to be thinking, “Why is that old codger staring at me?” Much like the Jeff Daniels character in Woody Allen’s THE PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO, this character on the screen seems to be aware of the one watching him.

I have a joke I have told for years.

As I sat alone in my room, sad and lonely and without a friend, a voice came to me from out of the gloom and said, “Cheer up. Things could be worse.” So I cheered up — and sure enough — things got worse.

That little joke can serve as a preview for my next voyage on the Enterprise!

The journey continues

This has always been one of my favorite episodes, for Diana Muldaur and David Frankham, and I hadn’t realized how much the poor Ambassador-in-a-box was dragged into the episode where he didn’t belong. There are some really nice moments in here, thanks to you and also George Duning’s lovely score. Good point you make about female roles in 1960s TV — maybe that’s why so many women love “Trek” and what took it often out of the typical. Trek always had lots of women, and not just as love interests. And now they don’t even HAVE any guest stars on shows, male or female.

I really enjoyed reading this write-up! Thanks again for sharing these memories!

I guess Gene Roddenberry also liked Diana Muldaur’s performance. Two decades later she became a regular for one season of Star Trek: The Next Generation, with blonde hair this time.

The David Frankham photos are just simply wonderful…Life admiring art, or is that art admiring the painter? Like you say, “very surreal”. Brilliant!

So much fun Ralph! Confidentially, as a kid, watched the show because the girls were good looking in the jump suits! And, of course the tazers! By the way, Nimoy and Shatner both turned 80!

Here is the IDIC pin sold by Roddenberry, and the ad from 1969:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/birdofthegalaxy/3800826413/

Here is another great example of tampering. The box animation was awful and gave me a headache. I agree there was no need for it, and was really confusing. Kirk should have been gone after “Peace.” I am sure you followed the script, but”others” ruined a great story, by adding bits that made no sense. So much for creative control. Thanks again for the insight into this episode, Ralph!

Definitely a bit of an ‘acid trip’, as far as this episode is concerned. Whether it was the scenes involving Ambassador Kollos or the distorted POV shots.

I’m surprised that Bill Shatner and Leonard Nimoy objected to the usuage of the I.D.I.C. emblem. Oh, well…

I think the good far outweighs the bad in this episode. As for the mixup in the Transporter Room, maybe Kirk had his eyes shut… 😉 It is nice to see the fire come from the script and acting rather than the car chase mentality. But I did love those sixties fight scenes with Kirk ripping his shirt, etc. Another of the episodes I’ve come to appreciate more over the years. Next, my favorite episode…I can’t wait!

Another thought about the “Kirk remains in the transporter room after the beaming” problem. We see Spock specifically raise his visor prior to activating the transporter. The doctor and ambassador beam out. Spock removes his visor and looks at the empty transporter platform. Then we cut to Kirk, looking INTENTLY at the platform before he turns and walks out. This apparently very intentional sequence of cuts squarely places Kirk in a position to have seen Kolos during the process of beaming. Seeing this for the first, tenth, and fiftieth times, I’m astonished…was this just poor editing? Or, were we supposed to think that there was more story being told here. Maybe Kirk had become impervious to the sight of the ambassador after his emotional “meeting of the minds” with Miranda? (But that doesn’t make sense…Spock had a much more profound mind connection with Dr. Jones, and he still had to wear the visor in the transporter room.) You see, I trusted Star Trek so implicitly, my mind wanted to search for meaning to explain something that looks like an error. Surely, this series with such sure-footed, complex story telling wouldn’t make a MISTAKE showing Kirk, visor-less, after Kolos beams out! Obviously, they’re trying to tell us something! But in the final analysis….nah. I have to accept this was editorial malfeasance (I can’t even call it negligence), now that Mr. Senensky has confirmed that the intention was to have Kirk leave the transporter room before Kolos and Jones departed. Thanks for clearing up the mystery, Ralph!

Thanks for telling this story…I did in fact notice the “gross error,” and it’s very interesting to know the story behind it.

Are you ever going to do a writeup of “Return to Tomorrow?” From what you say about it here it appears you didn’t enjoy filming it, but I’ve always liked that episode and would love to know more about it.

I find that I am going back and doing posts on shows that I skipped over. I just may decide to revisit STAR TREK and write about RETURN TO TOMORROW.

Hooray!

Hi Ralph — I haven’t written in awhile–I hope you are well!

I am just now watching “Is There In Truth…?” and once again something occurs to me that I don’t think has ever been asked or discussed regarding Miranda’s choice to devote her life to Kollos. She says to Marvick, “I simply can’t love you the way you want me to,” and seems to have broadly rejected the possibility of a long term relationship with a human male. Did you sense any insinuation in the script that Miranda was lesbian? I have the feeling even asking the question might enrage some, who would rightly say that just because Miranda chose to be with Kollos does not mean or require there to be a sexual connotation to either her devotion to the ambassador or her choice to not commit to a relationship with a human male. I only ask because almost every male in this episode seemed to be dogging Miranda…Kirk, McCoy, Marvick, even Scotty to a small degree. She almost seemed to be saying to all of these men “just leave me alone.” I’m only responding to a thought that occurs to me whenever I see the episode, and to all who would think I am making assumptions, or judgments, about Miranda’s motivations, believe me, I am not.

No, I did not consider that, probably because I recognize how seductive power can be. Personal power or powerful people. A modern example might be the Clintons.

There are also some who claim there was an unspoken gay relationship between Merik and the Proconsul in “Bread and Circuses”. But I don’t think it was ever intended by the writers of the episode or anyone on staff.

Very true. I do wonder, too, exactly what power Kollos had over Miranda. Specifically, why did she scream when she went alone into his room to get “set straight” that she couldn’t pilot the Enterprise? It was quite a blood-curdling reaction…what did he say that elicited such a shriek, I wonder?

Good! The aim of powerful drama — always leave them wondering, rather than wandering!

By the way, Ralph, I too vote for you to write up your Return to Tomorrow experience. I found this late in season two episode moody, eerie, as if I had really been taken someplace deep and unknown in space to meet these highly evolved beings buried deep in rock. The millenia-long-love-affair between Sargon and Thalassa was heartfelt and moving. And, of course, Kirk’s “risk is our business” speech rises to the very top of iconic moments in Trek lore. I’m deeply curious to hear what the director felt were the weaknesses of the script, performances, or production. Share, Ralph, share!

It’s the next post!

This was one of those episodes that went totally over my head when I was young. All I could remember was that awful metal box…don’t look in the box! As a grown-up, I now realize it is deep and complex. Even the show’s title is like a philosophical riddle…”Is There in Truth No Beauty?” How should I answer that? Is there an answer to that? I’ll bet I’m not the only one who has watched it numerous times, in order to figure out what the heck was going on.

An odd coincidence: Jessica Walter was not available to play Miranda. At this time, she may have been working on Charlton Heston’s football movie, “Number One”, playing Heston’s wife. Guess who played ‘The Other Woman’ in it? Diana Muldaur!

Recently, I was watching a randomly selected episode of ‘The Virginian’ on the Internet with my dad. When Diana Muldaur appeared, we had this exchange:

Dad: Who is that?

Me: Diana Muldaur

Dad: Where have we seen her before?

Me: She did Star Trek twice.

Dad: Which ones? (later, we went to your website!)

That’s Diana Muldaur…she has an exotic attractiveness combined with sort of a blue-blood coolness that makes you sit up and ask, “Who is that?” Perhaps I’ll come up with a name later, but I can’t think of another TV guest star actress who was like her during her peak period (mid-‘60s to mid-‘70s).

Diana did one of those TV archives interviews on the Internet last year. Here’s a quote regarding this episode:

“The whole script was thrown out as we’re sitting there about to start shooting, and hour-by-hour we would get pieces and none of them were in order.”

This is not a knock – she LOVED this episode (and doesn’t remember much of ‘Return to Tomorrow’). I know you had a re-write regarding that dumb IDIC, but how extensive could it have been? Perhaps you’re both saying the same thing in different words.

Most movie aliens look like the monster in the 1951 The Thing, a guy in a rubber suit. Even today in most TV sci-fi shows the aliens are just actors with make-up who walk with two feet, have mouths and hands, and speak English. What I always liked about the cloud creatures in Metamorphosis and Obsession was that they weren’t the typical people-dressed-up-as-aliens alien. I thought, the Medusan, who lived in a box, and didn’t look like anything corporeal but rather abstract as an edited collection of color, got across the idea of something so completely foreign to our human way of understanding, that it was a real invention, a very novel way of doing an alien in TV/movies. Now I find that this depiction wasn’t part of the original script, not part of the director’s intention, and that, additionally, the director considers it tasteless. I respect a writer’s and a director’s intentions about a show first, so I wonder how I’d feel about this episode if I’d seen it with the “inventive” alien absent as you originally intended it and shot it. Even though I consider the color-flash alien a very neat idea, perhaps the episode would play more tastefully without ever seeing what the Medusan looks like. In any case, I’m sorry that this episode wasn’t under your complete control and wasn’t issued in a final form you would have preferred.

It’s funny about that ending. Even as a kid, the inconsistency with Kirk viewing Dr. Jones’ final transporter moment hit me in the exact opposite way than many people. I immediately recognized the danger Kirk should’ve been in, but instead of Kirk making the mistake by not having the visor, I’ve just as often felt that Spock shouldn’t have had on a visor also. Since Dr. Jones was now “one with the Ambassador” much the way Spock had been earlier, she was now his beautiful mind inside her beautiful body and should’ve been safe to walk around, interact, and transport at will – and I assumed that there was now nothing in the box. So, maybe the scene could’ve been played with no visors and actually no box. ……or maybe they should’ve just cut it the way you’d intended. …still one of my absolute favorite episodes of any Trek series.

Thank you Mr. Senensky for these blogs about the episodes you directed. They are quite interesting to read!

I guess I don’t understand why there is an inconsistency in the final transporter scene. Kirk and Spock are walking around the transporter for the entire scene with the Medusan’s box sitting RIGHT THERE in plain view, and it’s not affecting them at all. Why should they suddenly need to don a visor (or in Kirk’s case, leave the room) once the transport occurs? It’s not like the box opened during transport. If Kirk is fine being in the same room with the closed box in plain view for several minutes, why should he suddenly need to leave the room if the box is going to remain closed during transport?

My understanding was that during the transport (and I certainly am no scientist) the body or in that case the Ambassador’s box was destabilized so that there was the possibility of his leaving the enclosure.

Thanks for the quick reply!

I guess that makes sense. And actually, that would be consistent with the opening scene where Kirk had to leave the room and Spock had to put on the visor before he beamed them up. Ok, nevermind, I am convinced!

I don’t quite understand, or agree with, Ralph’s statement

“Now STAR TREK had a standing rule that guest stars could not repeat unless they were coming back to play the same role.”

“Star Trek” only did that only ONCE, with Roger C. Carmel appearing as Harry Mudd over two distinct and independent episodes (the “The Cage” does not count since characters obviously had to carry over from Part 1 to Part 2), whereas numerous actors besides Diana Muldaur — Mark Lenard, William Campbell, Barbara Babcock, Skip Homeier, Laurence Montaigne, Ian Wolfe, Morgan Woodward and Jon Lormer [three episodes] — appeared in more than once episode in which they played an entirely different character.

I too have been surprised at this late date to discover what you are discussing. But I WAS THERE! I know the conversations that went on involving the casting of Diana a second time!

Wasn’t Bruce Hyde on twice as Lt. Kevin Riley?

More importantly, may I add my Thanks! to Mr. Senensky for providing so many great articles on his blog here about Star Trek, Route 66, and other great shows he was involved in. It is enjoyable and that little bit of enlightening (sometimes more than just a little bit) to read them.

Live Long(er) and (continue to) Prosper!!

Rich, I wish I could answer you question, but I really don’t now about Bruce Hyde.

I remember Bruce Hyde/Lt. Riley from two first season episodes, so that was just before you worked on Star Trek.

Among many other great things I’ve read on your site, on a small level, I enjoy the fact that you’re from Iowa. I was born in Sioux City, but have most of my life in California. Nice to see another Iowa connection to the world of Star Trek (a certain Captain being born there as well…). 🙂

I too have spent most of my life in California. — actually over 2/3’s of it!

Bruce Hyde played the same character twice. Also, Michael Barrier played Lt. DeSalle in three episodes (including “This Side of Paradise”).

I’m thrilled to be able to read about what went into the filming process of episodes. I didn’t know there was a problem with Bill and Leonard and the IDIC pin (I thought the ideals of IDIC so central to the meaning of Star Trek as a whole. I wish it had been brought into ST lore earlier. Kirk and Spock lived that ideal their differences together made them stronger.)

I loved Diana Muldaur, she did an excellent job in this ep and Return to Tomorrow.

Thanks, Mr. Senensky, for your primary account of this episode, one of my absolute Top Fives in TOS (“Metamorphosis” is another). During my four decades of enjoying ST never was I distracted by the chaotic flashes & animation of Kollos’ public appearances. I think since the story had already, to me anyway, introduced the Medusans as having a talent that Star Fleet wants — their navigational success, which Kirk praises as “a fine art” — I felt led to believe the Ambassador was already benevolent and respected his humanoid companions. In fact Kollos (via Spock) apologizes for their troubles. After reading your blog, however, I can see that those ghoulish effects are inconsistent with Kirk’s log: “…the thoughts of the Medusans are the most sublime in the universe”. Perhaps yet another example of truth & goodness being associated with beauty by default.

You may know that Trek.fm just aired a cool podcast on about the episode. I found it a good treatment & the episode was esteemed, but I wish the speakers had considered your own views beforehand.

https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/standard-orbit-star-trek-original/id725509170?mt=2#episodeGuid=7ee9fc3ce889cf524e30f8d9b4672f89

BTW I loved as well the Waltons episodes you directed. And Fred ‘Loskene’ is now on my own Do-Not-Hire list! Take care.

Pingback: Freiberger’s Last Word | The Classic TV History Blog

“Now STAR TREK had a standing rule that guest stars could not repeat unless they were coming back to play the same role.”

If they had that rule, they violated it a lot. The only guest star that came back for a repeat role was Harry Mudd. And a few minor crew members, like Kevin Riley, Mr. Leslie, and others.

There were more people who came back in different roles. For example, William Campbell (Trelane and Koloth), Phylis Douglas (Yeoman Mears and one of the space hippies), Diana Muldaur (covered in this article), Mark Lenard (Romulan Commander and Sarek), Majel Barrett (Number One and Nurse Chapel), Barbara Babcock (Trelane’s mom, Philana and Tholian Commander). Probably a lot more. If a director really wanted someone, it might be hard to deny them.

But Graeme, I WAS THERE! I requested Diana Muldaur in spite of the fact that I WAS TOLD actors could not return in a different role. A CONCESSION was made because the other actresses we sought were not available. And as I reported in this post, at the first screening of dailies, after her first scene Robert Justman said, “I wonder what she will look like in a RED wig!”

William Campbell was a close personal friend of Gene Coon (and of James Doohan as well), Majel Barrett was Roddenberry’s mistress and soon-to-be-wife. Mark Lenard resembled Leonard Nimoy so much, I think they jumped at the chance of him playing his father, even though he appeared in a different role earlier. Phyllis Douglas played minor roles in both episodes, two years apart, I don’t think they even realized it was the same actress.

So, yeah, I think there were exceptions for this rule, but most of them had a good motivation.

Like you, Ralph, I like to think we all mentally mature with age. In 1969, I was 14 & wasn’t really knocked out by “Is There In Truth No Beauty”, but now I’m 65 & I “get” it.

Perhaps Kirk didn’t need the visor because he ‘s… ALREADY INSANE???!!! 😉

One has to wonder if the “re-cast rule” was mainly applied to guest actresses, as female stars tend to stand out among a mostly male cast?

I admire Shatner & Nimoy for challenging Roddenberry’s obvious ploy to exploit the series to peddle cheap jewelry. Very brave; how many actors today would call out their own executive producer? That’s integrity!

Miranda is not gay; some women are so dedicated to their work, love is just not an option.

My favorite scene is Kirk’s heated argument with Miranda over Spock, then suddenly exits & admits to McCoy that he may have gone too far. Wonderful acting, beautifully directed.

Again, you did that; that’s you, Ralph; & we’re all the richer for it!

Mr. Senensky – Like you I was bothered a lot by little snippets of that box popping up where it didn’t seem to belong, but the “exit” scene, after Miranda has made the meld with Kolos and transports off the ship with him (I guess “him” is right), while Kirk remains without a visor but Spock put his on – didn’t bother me. It settled right into my brain that since Miranda has made the meld, the severity of the threat Kolos in his closed box presented wasn’t as great, and it was all right for Kirk to remain as long as the box was closed. Spock putting the visor on as he transports Miranda and Kolos away – I saw that as a kind of tribute by Spock, a tip of the hat to Miranda’s accomplishment and Spock placing himself a little below her on the victory stand. I don’t know if that’s what I was supposed to see, but that’s the way it hit me.

I did love your use of the fish eye lens to enhance the effect of insanity. The scenes wouldn’t have been half as alarming without it.

Dear Ralph,

just watched this episode for the first time, really enjoyed the reverse angle shot from the turbolift onto the main bridge. We always see the main cast from in front instead of from behind and it’s a powerful effect, wondering how this shot came about?

Simple. I just asked that the back wall of the turbolift be removed and the camera could then film from behind the turbolift’s occupants.

Very nice! Good to be able to pull out a wall and get the shot. And on the artistic side, wondering how showing the actors from behind changes the dynamics of the scene?

A good actor works his back as much as his a__!

good to know that some things will still be true in 300 years’ time!

Dear Mr. Ralph Senensky,

Phenomenal stuff to read and revel in after watching so many of these sensitive episodes. “Metamorphosis” and “Obsession” were tremendous and especially “Bread and Circuses”, as well for being so daring and spiritually “on point” to actually state the words “the Son of God” by Uhuru!! Almost makes one believe in foreshadowing, destiny and the eventual Revelation as foretold in the Bible. Praise be to the Lord.were always two of my favorite episodes.

On the personal side, I wanted to impart to you extreme thanks for your time, talent and contribution to this TV franchise that so many million of people have enjoyed as pleasant entertainment. Especially I thank you for your extra dedication and devotion to your fans by replying as often as you have on this Blog considering you are much, much older than many of us and I pray you are still in good health and spirits to read and have these “fan” letters repay you in some small way for the gift you have given all of us in this Star Trek pleasure “trip”.

Bless you and your family.

Sincerely,

Tim Fremuth