FILMED December 1970

First a slight correction in the interview: Lenny Horn was an associate director, not an associate producer, on PLAYHOUSE 90. He sat at the control panels next to the director during the airing, working a step ahead of the director preparing the cameramen via headphones for the upcoming shots.

The following Tuesday after completing TO PLAY OR NOT TO PLAY I was filming at the Partridge family house for the first time. It was on the Columbia Ranch on what was known as the Blondie Street, which had been built somewhere in the early to mid 1950’s, modeled after a Sears, Roebuck & Co. house plan.

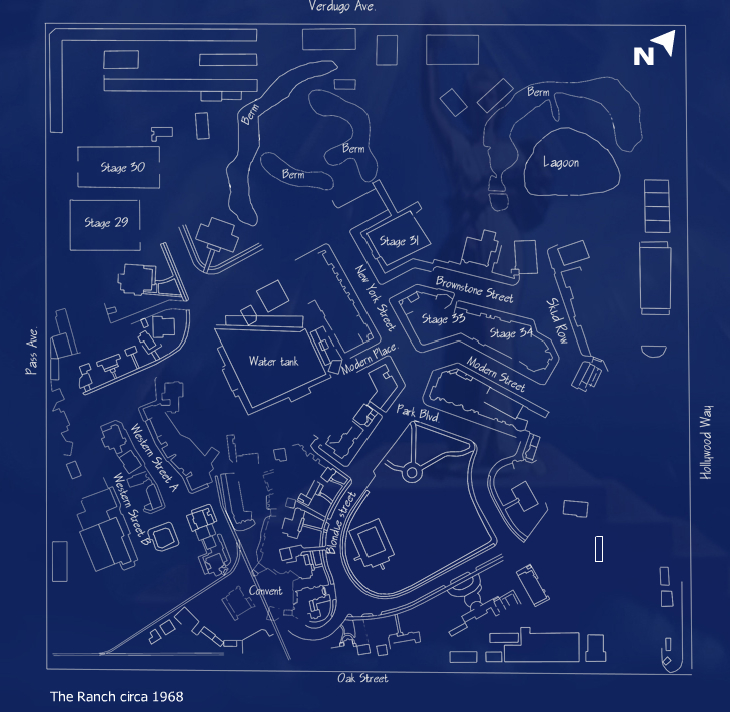

Map of the Columbia Ranch

Driving onto a studio lot was exciting, but that was because of the ghosts of the past that seemed to hover, not because of its visual attractiveness. There were long avenues lined by the imposingly cold concrete walls of the sound stages. The magic occurred when you entered those sound stages; or when you went out to the backlots. I think that was why I found it so charming to drive onto the Columbia Ranch lot, because its back lot literally greeted one at the gate with its tree-lined residential streets and parks.

The interior of the house was on Stage 30, a short distance from the exterior on Blondie Street.

Keith’s “I’m thinking, I’m thinking…” came from one of the classic comedy bits of all time. In a skit on the Jack Benny radio show in the thirties Jack was at the racetrack when a racetrack tout (I’m sure it was Sheldon Leonard) accosts him with “Your money or your life.” Silence. Again, more insistently, “Your money or your life.” Again silence. Then (very threateningly) “I said your money or your life.” And Jack’s response, “I’m thinking, I’m thinking.” I’m proud to admit, I remember listening to that original broadcast.

When I filmed the musical number in WHEN MOTHER GETS MARRIED I had strong reservations about the group appearing in a nightclub. I felt a rock group with minors would not be playing in a nightclub; I thought they would be performing in concert halls or on college campuses. But the need to have Shirley’s beau close enough for an exchange of looks that triggered a montage kept me silent. Plot requirements in TO PLAY OR NOT TO PLAY also kept the musical number locked into being staged in a club set. Finally I had a script without those restrictions but with a problem. There was no auditorium set on the Columbia Ranch. I was sure there was one at the Columbia Studio in Hollywood, but since the musical number would not require a full day to film, that would have required an expensive move. So what do you do in a predicament like that? You steal! And when you do, you steal from the best. And that’s what I did.

Orson Welles did it first. Thirty years earlier in CITIZEN KANE he created a Metropolitan Opera set with a bank of spotlights.

Eighteen-year old Annette O’Toole was at the beginning of a long career. Had she been around back when Mr. Welles was directing, one of the studios most certainly would have put her under contract. There she would have been worked on by the make-up department, gowned by wardrobe, and cast in a succession of supporting roles that would have grown in importance as the studio groomed her for stardom. But by 1970 it was a different era. Roles in television shows replaced those supporting roles in feature films. An agent looking to book another job replaced the studio interested in hopefully developing a new star. Annette did not become a major star, but she was and is an extremely gifted performer. Today as she approaches her sixtieth birthday and is a regular on her third television series, Annette O’Toole is still acting before the cameras.

I loved the supporting character actors in old films. Claude Rains. Beulah Bondi. Edward Arnold. Alice Brady. Frank McHugh. Glenda Farrell. Allen Jenkins. Una Merkel. Frank Morgan. Edna Mae Oliver. Donald Crisp. Gladys Cooper. Edmund Gwenn. Anne Revere. Thomas Mitchell. Helen Westley. J. Carroll Naish. Mary Boland. Rhys Williams. The list is endless. Most of them had been leading men and leading women in film or on the stage when they were younger. But as they supported the leading stars of the day, they brought so much texture to the screen. Television in the sixties provided a place for those great actors still performing to ply their trade. It was also an arena where younger character actors could function and there was a wealth of them knocking at the door. Two of them, Joseph Perry and Carl Ballantine are about to make an appearance.

Of the seven PARTRIDGE episodes I directed, I felt the drama in this one was the most real, closer to the dramady of THE COURTSHIP OF EDDIE’S FATHER films. There was even an Andy Hardy-Judge Hardy father-son talk; only this time it was a mother-teenage son talk.

I admit I had a problem working in the half hour format. Being limited to around fifty minutes to present an hour length story had been difficult. Telling a story in less than twenty-four minutes was very restrictive. But a story does have to end.

(The film clip of me is from a recent interview by the Archive of American Television, a division of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation.)

The journey continues

Here’s some market research that would have delighted Screen Gems in 1970: My grandmother (age 61) discovered this series and informed my sister and I that WE should be watching this show, too.

Of course, we watched it…and we got the records…and we got the bubble gum cards…and we really thought the Partridges sang the songs! I’m a little more perceptive these days. Notice the 3rd video – the microphone is a least a foot away from Shirley Jones’ mouth when she ‘sings’. Regardless, she looked DYNAMITE doing it and you did everything right in this scene.

I don’t have a good memory for the stories in this series, but I recall one episode where Keith wanted to be on his own. He might have moved into a room over the family garage. Danny sold him what he needed at extortionate prices. One of the items was a sandwich bag of potato chips for a dollar. When Keith received it, he complained, “they’re crushed.” Danny replied, “the flavor’s still there!”

Love the blueprint of the Columbia Ranch. ‘Here Come the Brides’ was filmed in the three berms area (top-center). The beach from ‘Gidget’ was around the lagoon (top-right). The ‘Dennis the Menace’ playground and fountain are in the lower-center area.

FYI – a website called retroweb.com has a link listing all So. Calif. TV studios & ranches used since the beginning of TV (includes overhead photos and maps). It also lists what shows were done at which studios, but it’s not 100% complete.

Regarding the mike in the 3rd video: We weren’t recording; they were lip syncing to a playback. The mike was further away for the visual look. David was the lead singer, and Shirley was just part of the backup.

Hi,

Wonderful article! These are the kind of stories I like to find about the happenings on the Ranch ‘back in the day’. I have been researching the history of the Ranch for years now and posted some of it on my little website, http://www.columbiaranch.net. I would love to talk with you about any other memories you have of working there and thank you for using my map of the Ranch 🙂

Mischa

Ralph,

Without reading your description first I was just thinking when watching this tonight, how good looking the song sequence was. David and especially Shirley really looked good energetic! And again many thanks for your notes from your journey!

You had no way of knowing you were directing the B side of their future million selling hit, “Doesn’t Somebody Want To Be Wanted”. With the A side never getting a performance video made, it was essentially up to you to sell that single. Boy did you ever. Your video inspired me and countless others who were indifferent about the A side to shell out our allowance money to buy this record. Too bad you didn’t get a percentage of the profits as a result. I can only imagine the reaction when everyone involved with the program saw the final product. We know one response. Get him scheduled for more episodes!