FILMED August 1974

From its very beginning television had a voracious appetite for product. For just the evening prime time airing hours of 8:00pm to 11:00pm (an hour earlier in the central part of the country) each of the three major networks (CBS, NBC and ABC) needed 21 hours of entertainment per week for a combined weekly prime time total of 63 hours. That’s a lot of entertainment. To help fill this vast void the networks looked to the movie studios where stockpiles of old films were stored. At first reluctant to aid those they considered their competitor for the nations’ attention, the studios soon realized there was gold in them thar vaults, and movies soon became an important part of the network schedules. I remember on my first day filming STAR TREK out at the Disney ranch, as we prepared to shoot the master of a scene Bill Shatner asked if I was planning to shoot close-ups. When I responded that I wasn’t, Bill shook his head and said, “This is television” I quickly answered, “You know that show that’s beating you in the ratings? Movies!” Original movies made especially for television soon became a part of the mix. In 1969 the head of prime time programming for ABC, Barry Diller, went a step further and created the ABC Movie of the Week, a weekly television anthology series featuring made-for-TV movies. The Movie of the Week provided ABC (long a distant third in the ratings) with a bona fide hit and helped establish the network as a legitimate competitor to rivals CBS and NBC. The Movie of the Week originally aired on Tuesday nights at 8:30 pm. Beginning with the 1971 season, ABC added a second Movie of the Week on Saturday night and adjusted the titles of the shows to Movie of the Week and Movie of the Weekend. In 1974 I returned to Spelling/Goldberg Productions, where I had directed THE ROOKIES two years prior, to direct DEATH CRUISE, a suspense Movie of the Week.

THE CRUISE was the title of the show when I reported. The name was changed sometime between my director’s cut and the answer print. Aaron Spelling greeted me in his office and had one request. He asked me to capture in the film the kind of suspense I had created in a scene from TO TASTE OF TERROR, which I had directed for THE ROOKIES.

DEATH CRUISE had an eleven day shooting schedule, with three days scheduled to be filmed on the Queen Mary (docked in San Pedro), a day at the beach and seven days on the 20th Century Fox lot on West Pico Boulevard. Our goal, as with all movies made for television, was to produce a product of feature film quality on a television budget. DEATH CRUISE had a final running time of 73 minutes; with an 11-day schedule that averaged out to about 6 ¾ minutes of the final film per day. Forty years earlier in 1934 W.S. Van Dyke, a director known for his speed, had filmed THE THIN MAN in three weeks (eighteen days), that being a time when the studios worked a six-day week. THE THIN MAN’s final running time was 91 minutes; with an 18-day shooting schedule that averaged out to 5 minutes of the final film per day. The big Oscar winner in 1934 was IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT, a Columbia film shot at what was known as the “poverty row” studio. It was filmed in four weeks (twenty-four days). With a final running time of 105 minutes, that averaged out to 4 minutes of the final film per day. The problem that we faced that I’m trying to present can be illustrated most effectively by simply stealing from President Clinton’s recent speech when he said, “It’s the arithmetic.”

I considered the script for DEATH CRUISE to be a rip-off of Agatha Christie’s play, TEN LITTLE INDIANS, filmed by 20th Century Fox in 1945 but retitled AND THEN THERE WERE NONE. Twenty years earlier in 1954 I had directed a production of the play at the Des Moines Playhouse in Des Moines, Iowa. But DEATH CRUISE was also influenced by MGM’s GRAND HOTEL, filmed in 1932. That film was the first in which the studio that claimed to have more stars than there are in the heavens, put five of them (Garbo, Crawford, Beery and the two Barrymore brothers) into one picture, creating an all-star line-up tradition that is still with us. For DEATH CRUISE I had eight guest stars, all well-established performers in television, including an Oscar winner, Celeste Holm, a Tony-winner, Tom Bosley and an Emmy- and Tony-nominee, Polly Bergen.

I’m positive the studio had enough shipboard set pieces from their productions of TITANIC (the first one with Clifton Webb) and all those Alice Faye musicals, so that we could have constructed sets and filmed everything at the studio, but I’m glad we didn’t. Arrangements were made to film aboard the historic Queen Mary, now a tourist attraction based in San Pedro. Filming aboard the Queen Mary widened the shots I could make, and the stairways between decks gave an added scope that would have been impossible to duplicate on the soundstage.

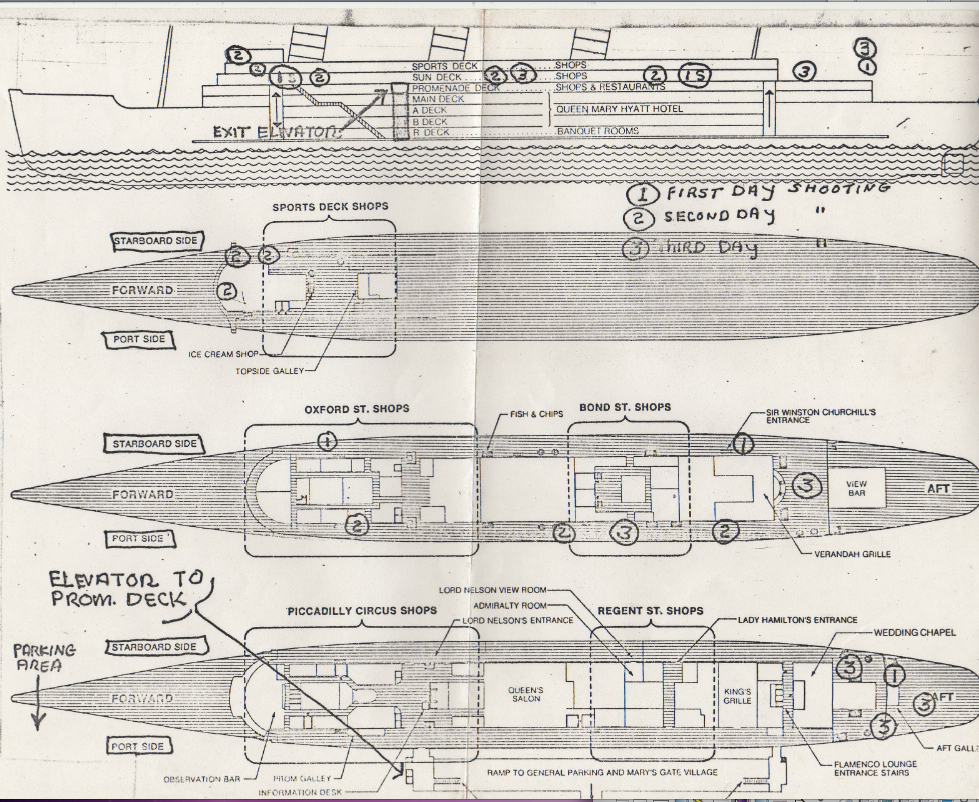

Our third, fourth and fifth days of filming were scheduled for the Queen Mary. Once I had selected the sites on the ship where I would be filming, the art department provided me with a “map” of the ship showing the locations we would be using.

The interiors filmed at the studio included the couples’ staterooms, the captain’s quarters, the ship’s corridors and the dining salon.

The dining salon sequences were filmed on the sixth day, on the second Monday when we returned to the studio after our three days of location on the Queen Mary. With a 7:30 am crew call I was ready to say “action” at 8:00 am, but two of the actors were missing — Kate Jackson and Edward Albert, who were cohabiting at the time. It was 10:00 am when the two finally arrived on the set and with no apology took their seats at the table. Since this was a Spelling/Goldberg production, and Kate was one of the stars of their hit series, THE ROOKIES, and since no one on the production staff was voicing any concern about their late arrival, I held my tongue and proceeded with the day’s work. I had worked with Kate two years before when I directed two episodes of THE ROOKIES, and I thought she was an exceptionally talented young actress. She was twenty-three years old at that time, and had recently completed an eight-month run on the hit ABC daytime soap, DARK SHADOWS. With THE ROOKIES (also on ABC) in its debut season and not yet declared the major success it was to become, there had been no sign of this lack of professionalism, this flaunting of “star” power. And truthfully, I did not blame Kate for this misbehavior. I blamed the system. Gone was the discipline of the old major studios, when young actors, newly put under contract, faced quarterly options if they misbehaved. Gone were the days when those young actors had the role models of the established stars with whom they worked. I saw a great interview on television when Alexis Smith told of an incident early in her career when she was cast opposite Clark Gable in a film. One morning with an 8:00 am call to begin shooting, she was still in makeup. On the set Mr. Gable looked at his watch, saw the time and said, “Thank you, gentlemen; I will see you tomorrow.” And he left. Alexis said she was never late again. It seemed to me that television producers found themselves in an untenable position. It was the networks that held the power. When BEN CASEY became a major hit with Vince Edwards as its major attraction, he was beyond being disciplined. The producers needed him to keep their show on the air. His was unfortunate behavior that if not rampant, occurred all too often.

This was the first time I worked with Polly Bergen, but our paths had crossed many years before, twenty-two to be exact. In 1952 I was an assistant director at the Chevy Chase Summer Theatre in Wheeling, Illinois, a city north of Chicago. One day the producer sent me into the city to one of the theatres where a big star (whose name I have forgotten, but it might have been Danny Thomas) was headlining the stage show. I think the mission was to try to secure him to guest at the summer theatre. What I remember most about that day was seeing twenty-two year old Polly, a young singer appearing in the show, hovering backstage. You know, I don’t remember if I ever mentioned this to Polly.

The first time I worked with Richard Long was on THE BIG VALLEY, but his role in that film was strictly peripheral. Later I directed six episodes of NANNY AND THE PROFESSOR in which he co-starred. Richard had burst into movies right out of high school at the age of eighteen. It’s interesting to see his early work when he played Claudette Colbert’s son in TOMORROW IS FOREVER, appeared with Loretta Young and Orson Welles in THE STRANGER and was one of the Kettle sons in the MA AND PA KETTLE series. He was a handsome, callow youth riding on his good looks. But he learned his trade and became a very fine actor. I thought Richard’s major talent was playing romantic comedy. He had an impeccable sense of timing.

The first time I worked with Michael Constantine (Dr. Burke), was in 1962 when he played the father in my Equity Library Theatre West production of Clifford Odets’ GOLDEN BOY. The following year we worked together on ARREST AND TRIAL.

The huskiness in Kate’s voice was not a God-given gift. Before each scene in which she appeared, the rest of the cast and I would hear her screaming off in a corner of the soundstage. Celeste and Tom were amused, and I wish I remembered some of the caustic remarks they made. I shuddered to think what Belle Kennedy, Patsy Challgren and Jack Woodruff would have said if they had visited the set. They were the speech instructors at the Pasadena Playhouse who drilled into us that our vocal chords were our most valuable possession, and they had been demanding and relentless in their efforts to teach us to cherish them, to guard them, to learn to use them to create perfect, rounded, stress-free tones

The first time I saw Celeste Holm in person was in 1945, when she came to Europe to entertain the troops with her one-woman USO show. She was a formidable talent, a warm personality with an acerbic wit. I loved the story I had read that when a fan asked which nun she had played opposite Loretta Young in COME TO THE STABLE, she responded, “The out of focus one.” I witnessed that wit on our set. If Kate, when playing a scene, was asked a question, she would repeat the last word of the question when answering. As an example in an exchange that did not make it into the final cut, Elizabeth (Celeste) asked, “Do you have any children, Mrs. Radney? Kate’s scripted response was, “No, we don’t,” but she said, “Children? No, we don’t.” Without dropping a beat and with a smile on her face Celeste stared at Kate and said, “Don’t do that, dear!”

Ralph, you slightly undercounted the network calendar hours that needed filling – primetime still started at 7:30 PM on weekdays in 1969. Also, Sundays were longer than three hours.

I don’t remember ‘Death Cruise’ when it came out. I have some guesses regarding this whodunit, but I’ll keep it to myself.

Did you know that an episode of ‘Kolchak: The Night Stalker’ (“The Werewolf”) was also filmed on the RMS Queen Mary in 1974? It was broadcast two days after ‘Death Cruise’. It’s on Youtube and I think they filmed the real cabins and corridors of the ship.

I don’t know who the target audience was, but those ABC-TV movies were a BIG talking point on my elementary school playground. Even if a few plumbed the depths of stupidity, we still watched them. ‘Killdozer’ from ’74 (slow-moving alien-controlled bulldozer kills off really dumb construction workers) has cult status! ‘Short Walk to Daylight’ from ’72, which defied geological reality (NYC residents trapped in the subway system after an earthquake), is a classic! Finally, I and millions of other boys have never forgotten the network promo for ‘The Girl Who Came Gift-Wrapped’ in ’74: Richard Long opens his front door and receives Karen Valentine (only a bikini under her raincoat) for his birthday.

You are right about the time. I remembered that back in the 1950s CLIMAX started at 7:30pm on Thursday night followed by PLAYHOUSE 90 at 8:30pm. And I went on the internet and googled around to find out when they lopped off that half-hour, without any success. Thank you for remembering and not needing to google.

This article explains in detail the multiple primetime changes mandated or triggered by the FCC in the early ‘70s:

http://www.tvobscurities.com/articles/fall_1974_that_wasnt/

This is a quick reference I turn to if I’m curious about what shows competed against each other during a particular season:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_United_States_network_television_schedules

It’s probably 100% accurate for showing the September line-ups. However, it has holes when it comes to documenting mid-season replacements and schedule changes.

As always, very interesting. And I really appreciate your candor about Kate Jackson.

I believe Death Cruise was Richard Long’s final project. Can you tell any memories of him and of working on Nanny and the Professor.You directed the ‘broken golf club’ story on Nanny.

DEATH CRUISE was Richard’s last performance, and it was a shock when I learned of his death just a few months later. My first time working with Richard was on THE BIG VALLEY, but in the episode I directed his role was very peripheral. NANNY AND THE PROFESSOR was the most formulaic of the four comedy series I directed, but because of producer Charles FitzSimons’ intelligent guidance regarding the scripts and even more because of Juliette and Richard’s performances, it was far superior to what it might have been. He truly was a superb actor and one of the best at comedy that I’ve worked with. NO fuss, no muss. He was always prepared, always charming, both before and after I said “Action.”

” … He truly was a superb actor and one of the best at comedy that I’ve worked with. NO fuss, no muss. He was always prepared, always charming, both before and after I said ‘Action.’ ”

Thank you for the above comment. He died way too young, but left behind some wonderful performances.

In 2012, I enjoyed Death Cruise (which I’d never seen before) and wrote up this review for my blog:

Penned by Jack B. Sowards (one of the credited writers on Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Kahn), 1974’s Death Cruise is more of a murder mystery than a flat-out horror tale. Three couples (the Carters, the Radneys, and the Masons) meet on a cruise ship and realize that they all won their all-expenses-paid vacations from the same promotional company. Jerry Carter goes missing one night, and the crew concludes that he fell overboard. Elizabeth Mason dies seemingly from a fall down a flight of stairs, but the ship’s doctor concludes that she might have been murdered by blunt-force trauma to the head. After David Mason finds Sylvia Carter dead with two bullet holes in her, no one doubts that there’s a killer on board. The murderer seems to be targeting just the Carters, Radneys, and Masons, who may have crossed paths four years earlier in Atlanta. Ultimately the ship’s doctor pieces together some clues, and justice prevails. I won’t spoil the identity and motive of the person behind the deaths, but I will say that I perceived the final couple of twists as quite clever.

Death Cruise runs a mere 70 minutes, and it’s a fun ride with some enjoyable dialogue and a cool mystery at its core. The plot takes a good fifteen minutes to get well and truly underway, but soon enough the filmmakers set up some interesting questions about just what’s really going on. I was utterly blindsided by the ending, when the antagonist comes face-to-face with the ship’s doctor. This project is yet another long-forgotten made-for-TV gem worth tracking down.

Thank you Daniel. That may be the only time DEATH CRUISE was called a gem.

Pingback: Episode 45 is here! Cruise into Hell With Us! | Made for TV Mayhem Podcast

I watched Death Cruise again the other day on Youtube. Maybe it wasn’t a gem, but it was a fun “who is it?” more than a “who done it?” and it kept me occupied in a March snowstorm. Sad that it was Richard Long’s last work, but I’ll bet he had fun doing it. I’d followed his work for years and boy, he had me fooled. I especially liked the way you worked with the various stairways on the ship – it gave some good three-dimensional movement to the film that you are right, you couldn’t have matched in the studio.

You may not know this but RICHARD LONG made a week’s worth of appearances on MATCH GAME ’74 in September. He also mentioned he’d just completed making a movie he called “Cruise of Death”. I believe this appearance on MATCH GAME was his last of any kind.

I remember reading his obituary which stated he’d been hospitalized for a month before his death on Dec. 21, 1974 — four days after his 47th birthday. Long had had heart problems dating back to the late ’50s when he was only age 30.

The Match Game episodes are on YouTube. I think I read they filmed those episodes in late August 1974, and Death Cruise finished filming on September 2, 1974. I don’t think Long did any work after that. I remember that first heart attack of his – it was in April 1961, he was 33 and doing 77 Sunset Strip and I was disappointed he had to bow out. He was hospitalized for a month then too, and Juliet Mills said he knew he had problems when they were doing Nanny and the Professor but didn’t want to live like an invalid, so he didn’t.