FILMED October-November 1973

Not all of our location work was in southwest Los Angeles. The building and office for the man who was going to tear down the church to build his shopping center had to be an impressive building in an affluent area, a building that would have been standing in Los Angeles in the 50’s. It was not going to be found in the area where we had been searching for our church. We found it in the Bunker Hill section of downtown Los Angeles.

The secretary in Mr. Briggs’ office was Amentha Dymally. A decade before I had met Amentha, but not as an actress. I was directing NEVER TROUBLE TROUBLE TILL TROUBLE TROUBLES YOU on BREAKING POINT, a story of Rosie, a disturbed black boxer who seeks psychiatric help. In his sessions with the psychiatrist Rosie speaks of his past. We needed a seven-year old boy to play Rosie in those sequences. Now under ordinary circumstances the adult Rosie would have been cast, then a young boy to play the child Rosie, who looked enough like him that he could have been him as a child, would have been cast. But this was episodic television, so while the search for the adult Rosie went on, the casting director, brought in three seven year old boys. Our plan was that we would see the children, but hold off making any final decision until we had cast our adult Rosie, after which we would cast the young boy who most closely resembled him. One of the boys who came in was Amentha Dymallly’s son. The child was beautiful and absolutely enchanting. He was light-skinned with light brown wavy hair. His whole demeanor was sensitive and angelic. He had the qualities we were looking for in the young Rosie. We decided not to wait; we cast him on the spot. We hoped our adult Rosie would match him, but if he didn’t, make-up would solve the problem. We then cast a New York actor, Terry Carter, as Rosie. Terry was a dark-skinned Sydney Poitier look-alike

The day young Dymally was to shoot arrived. He reported to make-up, where I had given instructions on what I wanted. I could not stay in the make-up room to oversee, as I had to continue filming. When his make-up was completed, the make-up man brought him to the set for my approval. I took one look and said, “No. He needs to be darker.” They returned to the make-up room, and a short time later returned. “No,” I said, “He is too light, he needs to be darker.” Again back to the make-up room, and again a return to the set. “He is still too light. He needs to be darker.” I took the boy and the make-up man over to where Terry Carter was seated. “He is playing Terry as a child. His skin needs to be the same color.” The make-up man looked at me quizzically, as if I had lost all my marbles. “Well don’t they get darker as they grow older?” he asked. Now that was a funny line, but it was also shocking to me. A hundred and nine years after the end of the Civil War it was inconceivable to me that anybody with any intelligence could ask that question.

Joel Fluellen, one of the deacons in Will’s church, played Rosie’s father in that production. I had worked with Robert Do Qui, our Mr. Briggs, five years before on an episode of INSIGHT. Joel Fluellen was also in that episode.

Los Angeles, as late as the early fifties, still had the Red Car, a trolley line with cars running all the way from Pasadena to Long Beach and all stops in between. When I was a student at the Pasadena Playhouse in 1947-48, I remember riding the Red Car from Pasadena to Santa Monica. By the time I returned to Los Angeles in 1954, the Red Car was gone, although her tracks still ran down Santa Monica Boulevard, and buses were now the mode of travel. The production staff of our show told me that there was a company that had restored some Red Cars, mounted them on tires, and these cars were for rent. All I would have to do when filming them was prevent the tires from showing.

Fannie Mitchell, the lady who sat with Grandma on the Red Car, was played by Juanita Moore. Juanita had been in films since 1942, when she first appeared uncredited in STAR SPANGLED RHYTHM. It was a time in which few black people were given an opportunity to act in major studio films, and for black women, when they were cast, it meant being cast as servants and maids. When noted actress Hattie McDaniel was criticized for accepting such employment, she responded, “I’d rather play one than be one.” By the 50’s Juanita’s roles were larger and she appeared – with screen credit – in Rita Hayworth’s AFFAIR IN TRINIDAD, Barbara Stanwyck;s WITNESS TO MURDER and Glenn Ford’s RANSOM. In 1959 she was nominated for an Academy Award for her supporting role in IMITATION OF LIFE.

For the test scene that ABC required before casting the role of Sarah Douglas, we selected an important climactic scene between Will and Sarah. At the time the sets for the production were not constructed, so the tests were filmed in mprovised sets. I was not as restricted in my staging when we shot the scene in the real sets for the film.

Before the film went into its final stages of postproduction, it was sent to the network for approval. A request came back to add a voice-over narration. Once I delivered my director’s cut, I was at work on THE GIFT, my second episode of THE WALTONS. Although I was at the same studio where DREAM had been filmed, I was not notified of this request from the network, so I was not involved in the writing or the recording of the narration. I have very strong feelings about how narration should be used. I have read that Billy Wilder used the addition of narration after a film had been assembled when there was a need for clarity. Our original schedule had a full day’s work on a highway, filming sequences of the Douglas family’s journey from Arkansas to California. Midway through production it was decided to cut those sequences. Therefore when the family drove up to the church, a narration describing their difficult trip was appropriate. But narration should never tell what is going to happen, nor should it describe what is happening, which detracts from what is being presented visually. I thought an example of the latter no-no was the narration over the montage of Will’s seeking employment.

Our sound mixer did not want to use radio mikes on the actors when we were on location. In doing close group shots or close-ups, the mike boom works fine, but on wide shots and traveling shots, especially when there is surrounding distracting noise, I had always found the radio mikes attached to the actors’ costumes to be very effective. I did not view the rushes for the ten days of location filming. Only when I returned to the studio for the final sequences in the Douglas home did I learn that there was a sound problem, and that a great deal of the sound on location was going to have to be redone on the dubbing stage.

The unforeseen and unexpected problems that can arise when filming! I wanted a crying baby when Will was speaking to the young mother, but I ended up with a happy baby who didn’t want to cry. We tried everything short of child abuse. I think at one point I even pinched the child’s leg (gently, of course), but that just provoked more giggles. Then the social worker assigned to our set took me aside and taught me a very valuable lesson: how to make a baby cry. Just make soft crying sounds, and the baby will immediately start to howl. I did find out it only worked (at least for me) when a woman made the crying sounds.

Max Hodge was on the set every day of the seventeen-day schedule. Never again during my twenty-six years of directing film did I have the luxury of having the author of the screenplay present on the set in case there was a need for a change in script. And Max didn’t do it just this once because we were friends. Throughout his film career he always was on the set when anything he wrote was being shot.

That sequence offers proof of why a director needs to be involved in editing his film. In the editor’s first assemblage, he had not cut back and forth between grandma’s collapse and the basketball game. The camera moving into Grandma as she lay on the floor was one long continuous shot. It worked. It was still effective. But I had envisioned it the way you just saw it. I thought this way worked even better.

When I was directing a production starring Lloyd Bridges (a fine actor and a true gentleman) he always took the time on the first day a new actor joined the company to bring the actor over and introduce them to me. As they moved away, I would hear Lloyd quietly say, “He likes actors.” And I confess I do. I am awesomely impressed with their ability to lose themselves so completely in the scenes they are performing.

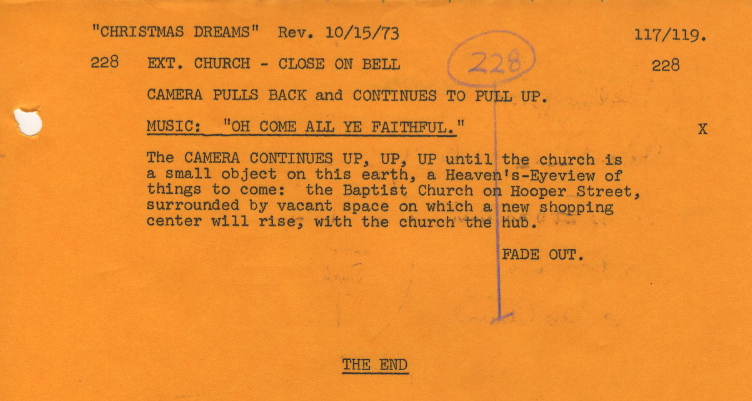

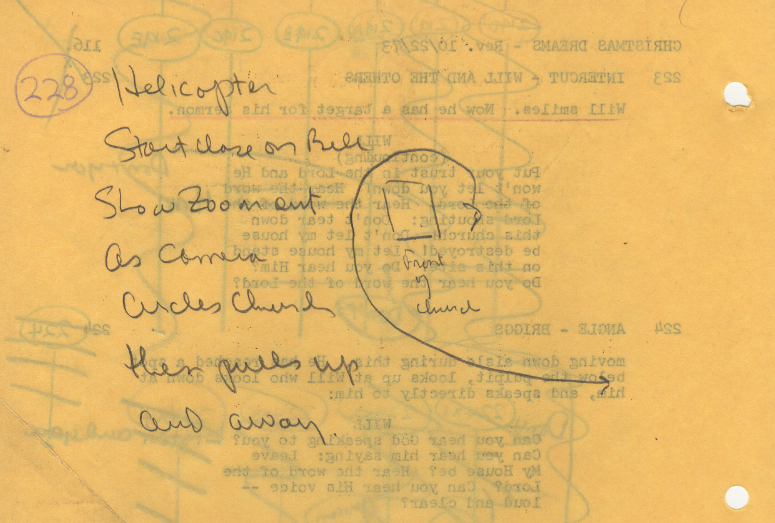

The filming schedule was completed, but there was one final scene in our script that hadn’t been scheduled to be filmed. I suspected that Neil Maffeo, the executive production manager, had visions of its not being filmed, of saving the expense the sequence would cost.

There was a screening of the film. It of course at this point had not been scored musically. But I remember that evening very well. Lee Rich, the co-founder of Lorimar Productions and the Executive Producer for this production was there. After the screening he enthusiastically declared, “This a brilliant film.” (You see why I remember the evening so well) And HE WAS THE ONE WHO ORDERED THE FINAL SHOT BE MADE.

I was in the helicopter when that shot was filmed. There was a telephone line that the pilot had to avoid. We did five or six takes.

The dreams of the Sweet Clover family all came true. The dreams of the producers of this production did not. A DREAM FOR CHRISTMAS did not become a series.

The journey continues

A Dream For Christmas will be broadcast on ME TV 12/06/13 8PM EST

I viewed this movie for the first time Friday evening, and found it to be excellent. The story was interesting and heartwarming. The performers (Beah Richards, Juanita Hall, Hari Rhoades, Lynn Hamilton, and all of the supporting cast) all gave first class performances. The production, direction, music, etc., were excellent. I enjoyed reading on this website, the background of this movie and how it was made. Thank-you Mr. Senensky, for this movie and this website. I hope that Me-TV makes a holiday tradition of showing this movie each year.

From your lips to God’s ear!!