FILMED October-November 1973

I directed twelve episodes of THE WALTONS. If I had filmed them back-to-back, they would have been completed in a little more than nine months. But I didn’t film them back-to-back, so the elapsed time from the start of the first show till the completion of the last show was five years. During that five-year span I also directed twenty-five other productions. The first of that batch away from Walton’s Mountain wasn’t that far away. Soon after I completed THE CHICKEN THIEF, my first Walton involvement, Lorimar booked me to stay on and direct CHRISTMAS DREAMS, a two-hour movie-pilot. I figured it must have been because they were pleased with my work on the mountain, otherwise why would they book a Jewish white man from the north to direct a Christmas show about a black family from the south.

I was sitting in my new office reading my new assignment. It was obviously an attempt to launch another series, a black family version of THE WALTONS. It was a story about a black minister who in the fifties moves with his family from Sweet Clover, Arkansas, to Los Angeles, where he had been hired by a church to be its new pastor. When he arrives he finds the church, in financial difficulties, is soon to be torn down to make way for a shopping center. And further, there is no money to pay the new minister. To help out financially the minister’s mother gets a job as a housekeeper with a white upper class Beverly Hills family, and thereon a lot of the script was spent in the Beverly Hills family home with sequences that I felt were stereotypical situation comedy. My heart was slowly sinking. The script was by John McGreevey, a fine writer whom I had never met, although I had directed several scripts that he had written. He was admired and well entrenched at Lorimar, having written eight scripts for THE WALTONS. Since I had just directed my first episode of THE WALTONS, I was well aware that seeking the kind of changes I would be after would be treading on thin ice.

Just then Walter Coblenz walked in. Walter and I had worked together a decade before when he was a second assistant director. Since that time he had risen in the ranks and become a producer. He had produced THE CANDIDATE starring Robert Redford and more recently had produced THE BLUE KNIGHT starring William Holden, a Lorimar-produced movie for television. Walter told me he had been assigned as the line producer for CHRISTMAS DREAMS. And then wasting no time he said, “We have to do something about this script. Why don’t we bring in Max Hodge to do a rewrite.” I was pleasantly stunned.

I have forgotten how Walter knew Max Hodge, but I had known Maxie since 1947 when we were fellow classmates at the Pasadena Playhouse School of the Theatre. After leaving the Playhouse I had produced and directed a production in Mason City of A STRIPED SACK FOR PENNY CANDY, a lovely play he wrote for his thesis at the Playhouse. But then there was a fifteen-year lapse in our contact. He had returned to Detroit, where he wrote-produced-directed Oldsmobile industrial musicals for General Motors, while I was on the journey I have been describing. In 1963 when I was directing BREAKING POINT, Max reconnected with me. He had left General Motors, returned to the west coast and was prepared to storm the gates of Hollywood. During the following year he did the usual knocking on doors. Some time early in 1964, influenced by my contact with DR. KILDARE, he started writing a script for that show. Over the summer, because of my familiarity with the show’s format, I was able to help him. That fall I was back directing my final DR. KILDARE. I was in postproduction when on a Friday I gave Max’s recently completed script to Doug Benton, associate producer for the show. Doug read it, loved it, bought it, and put it into immediate production starting the following Monday. Max wrote more DR. KILDARE’s, and when Doug Benton left that show to produce THE GIRL FROM UNCLE, Max was the associate producer. Maxie was one of my closest friends. Needless to say I heartily endorsed Walter’s suggestion to bring him in to rewrite our current script.

I don’t know what transpired between Walter and the powers at Lorimar, but the next thing I knew Max had been hired and the two of us set about redoing CHRISTMAS DREAMS. We started off by screening THE HOMECOMING — several times. That was the original two-hour movie written by Earl Hamner that spawned THE WALTONS. Our aim was to capture the charm and the drama of that family in the Douglas family in our teleplay. Where THE WALTONS reflected the trials of the depression years that a family faced, we wanted to present the trials a black family faced when it moved from the rural south to a big sprawling metropolis in the west. Our working format was simple. I was in one office, and I would plot and outline the sequences. Max, in an adjoining office, would write the sequences. And we each were a check on the other’s work.

We completed our first draft in twelve days.

There were two enormous tasks facing me: casting and finding the locations. There were close to fifty speaking roles, all black, and I think I saw every black actor and actress in Hollywood, and that included everybody from age six to still breathing. Beah Richards was a shoo-in for the Grandmother. I knew of her work in THE AMEN CORNER, a play she had performed in to critical acclaim in the Hollywood area. And of course she had been Sydney Poitier’s mother in GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER.

I don’t remember how many actors I met who were potential Will’s, but Hari Rhodes was the unanimous choice to play our minister. For Sarah Douglas, the mother, Lynn Hamilton was another shoo-in. I knew her work, because I had directed her in a play in the Los Angeles area. Lorimar favored her because she had a recurring role on THE WALTONS. But for some reason (and only for this one role) the network, ABC, required that we film and submit test scenes, and of more than one actress, so they could be the one to make the final choice. A dramatic scene from the script between Will and Sarah was selected, and I directed Lynn and one other actress in fully produced tests on film. Hari played Will with both actresses, and it was shot with full coverage, which was then edited. We did everything except provide a background music score. When the two tests were completed, the network was notified to come view them. The network executive assigned to this project didn’t come. He sent his young assistant to view the tests and make the selection. He was to be the one deciding who would play Sarah Douglas. I must interject here that there really was no choice. Lynn was far superior. But the assistant chose the other actress. We were stunned. This reaction went all the way to the top of Lorimar. It was my understanding at the time, that executive producer Lee Rich called Fred Silverman, the head of ABC, and told him that unless the network approved Lynn Hamilton, we would not make the film. Whether that phone call actually happened I can’t swear to, but Lynn Hamilton was cast as Sarah Douglas. And the young assistant shortly after this went to another network, where he took over as head of comedy development

The script was 113 pages long. Fifty pages occurred in the Douglas home and would be filmed on a set at the Warner Bros. studio. There were close to twenty-five locations to be found in southwest Los Angeles. Walter was acquainted with the area because of the location work in his production of THE BLUE KNIGHT. And it is Walter who introduced me to Japanese food. On our location scouting days, he took us to Tokyo Kai Kan, a restaurant in Little Tokyo, a section of Los Angeles close to where we were scouting. My cocktail of choice at that time was a perfect Rob Roy on the rocks. Our little group would crack up every time I ordered one. They thought I was doing it as a put-on to the Japanese waitress. Because many Japanese have trouble with their r’s, it could come out as a “perfect Lob Loy on the locks.”

Our story started in Sweet Clover, Arkansas. And where did we go to find Sweet Clover? We went to where the big boys used to do it back when they really knew how to make movies — the back lot of Warner Bros. Studio.

Some time during the trek from first draft to final print the name of the show was changed from CHRISTMAS DREAMS to A DREAM FOR CHRISTMAS.

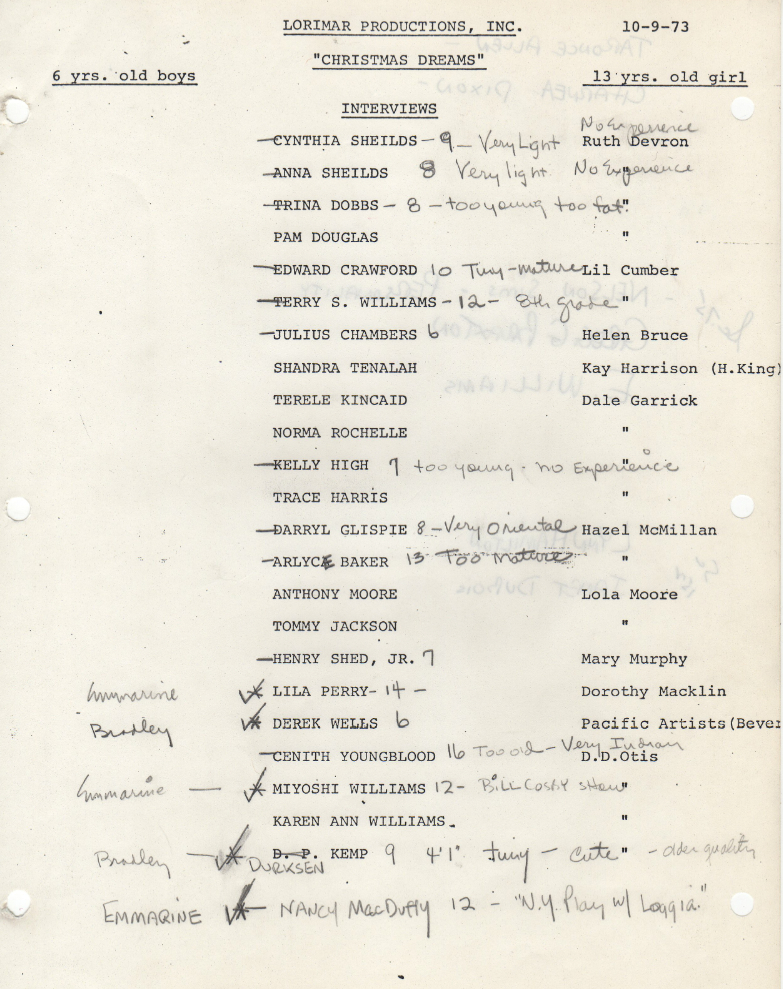

The most time consuming part of casting was auditioning the young people. I saw as many if not more of them to cast our four Douglas children pus eleven other family and friends as I did for the adult cast. Because it was October and children were in school, those casting sessions were held after 3:30 in the afternoon. Here is a list for just one day when I was interviewing prospective Emmarines and Bradleys.

Fifteen-year old George Spell was our choice to play Joey. George had been acting since he was eleven, but he didn’t come without a problem. As was the fashion in the seventies he had a very bushy Afro hairdo. But that was not the hairstyle in the fifties, when our story took place. And George wouldn’t even consider trimming it, even if it meant losing the role. So we agreed that nightly he would soak his hair with water and pull a silk stocking knotted into a cap over his head and sleep that way. It worked!

Thirteen-year old Taronce Allen was our choice to play Emmarine. A DREAM FOR CHRISTMAS was only her third film. Our Becky, Bebe Redcross, had less to do than the others, but she was a lovely child.

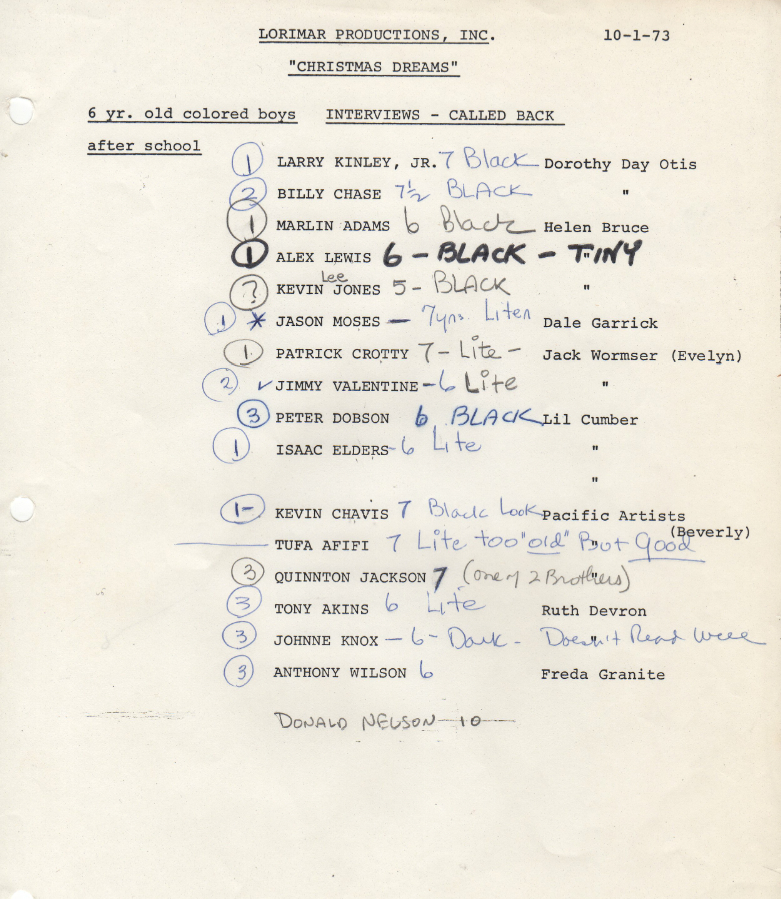

It seems like finding six-year old Bradley was the hardest. Here is a list of contenders for that role who were called back for a second audition. Oh to have had the digital camera of today back then to help me remember all those faces.

We cast Marlon Adams, who had never appeared in a film before.

Our scouting trips in southwest Los Angeles took us to probably every church in the area. When we finally found the one we wanted, it was truly a miracle come true, as Grandma says in the scene. The minister of the church told us that his church had serious financial difficulties, and the money they would be making because of our filming was going to solve their problems.

Cousin Clara was the largest female supporting role in the film. Dorothy Meyer had appeared in only three films before I cast her earlier that year in THE CHICKEN THIEF, with much less experience than most of the other actresses who auditioned. But she was such a fresh new talent with a wonderful robust quality and energy, she was the one I wanted for the role.

The actual church did not have a parsonage attached. But as long as I didn’t photograph the rear of the exterior of the building, no one would know. And by duplicating the double doors in the church in the design of our studio set of the parsonage, our actors were able to move from the church (in southwest Los Angeles) to the parsonage set (in Burbank) with no difficulty.

I was thrilled with the set that art director Perry Ferguson designed for the film. After the set was designed Max and I rewrote the scene when the family see their new home for the first time, incorporating the many details Perry had provided in the rooms.

The two church deacons were played by Joel Fluellen and Clarence Muse. Joel and I had worked together several times earlier, starting with his appearance in THE ICEMAN COMETH at UCLA, followed by his guest starring on BREAKING POINT. Clarence was truly a Hollywood veteran. He was eighty-four years old when we did this film. He told me he had come to Hollywood in the early thirties heading his own classical theatre company. He was a highly educated man, Phi Beta Kappa, but when he auditioned for the movies, he had to learn to talk and sound less educated in order to be cast. He appeared in over a hundred and fifty films in a film career that spanned fifty-eight years. He made only three more film appearances after this one before he died in 1979.

When I viewed THE HOMECOMING, I was impressed with the sequence where John-Boy and his six siblings trudged through the snow on their way to school. I decided I wanted to use our four siblings’ walk to school as a way of seeing the frightening but wondrous city of Los Angeles as they encountered her for the first time.

This film set in the fifties was a period piece. When doing a period piece, actors who are cast report to wardrobe before filming begins and are outfitted. Costuming our principal actors presented no problem. But the sequences on the street, and especially the sequences at the schools involved people who weren’t selected to appear until when we arrived at the location. Our costume designer, Patricia Norris, had a wardrobe truck packed with clothes of the fifties — boys, girls, men, women in all sizes. Hers was a gargantuan task. All of the students you’ve seen, all of the background people in all of the location sequences were provided with wardrobe by her at the location — sort of like drive-through costuming.

David Rose composed the lovely background music for this production. Harry Sukman, an Academy award-winning composer, had told me on DR. KILDARE a dozen years before of a technique in composing he had learned from Meredith Willson. I was aware when I was present on the recording stage when David conducted his score for this movie that he too was using that same attack. His score is melodic, emotional, tender and soaring.

Charles Washburn, the second assistant director on the show was a black man. I had known Charles when he was a DGA apprentice on STAR TREK. At my request he took Max Hodge and me to a Sunday morning service in a black Baptist church. I was fascinated by the vocal responses of the members of the congregation to the minister’s sermon, of the conversation between minister and parishioners that took place constantly. When we returned to the studio, Max added congregation responses to our church service scenes, and I encouraged more responses from the cast when I filmed.

To be continued

Ralph, wasn’t the DGA trainee from Star Trek called Charles WASHBURN? He later went on to become 1st AD, and returned to the “Trek family” to work on Star Trek: The Next Generation in the 1980s. He was even nicknamed “Charlie Star Trek” for his contributions to the two series. Sadly, he just passed away in April.

You are so right and I am filled with shame for my error. Charles contacted me by telephone some time ago, but after I had moved north. I am going to correct it immediately. And with an added look at the end credits for the show, I can now explain my lapse. In the end credits Charles’ credit is Second Assistant Director: Charles Walker.

Ralph, as to Lynn Hamilton’s casting and the call by Lee Rich, I’m positive you are right about Lee telling ABC she has the part or we don’t do the show.

Lee and Pippa had me to their home many times when I was young and starving. He could come across as a hard guy, but he had a soft heart. It was Lee who had Mitch Ackerman come to the set and put me on permanent salary. I’ll be forever grateful for that.

Lee had a hard and fast rule that the cost of each Waltons episode must not exceed the CBS license fee. I think this, at times, made him look like a hard guy, but in truth, he was a pussycat although he would never admit it.

Sadly, he passed just yesterday.

He gave us The Waltons, and employed many of us who benefit from it to this day.

Yes, I’m positive he stood up for Lynn.

Perry Ferguson, the art director on your production, has some impressive credits on his resume. At RKO he was the unit art director on “Bringing Up Baby”,”Gunga Din” and “Citizen Kane”.

I think that was his father.

A Dream For Christmas will be broadcast on ME TV 12/06/13 8PM EST

yayyyyyyyyyyyyy I cant wait

I would love to see this whole movie..

By reading my posts for A DREAM FOR CHRISTMAS – PART I and PART II you are seeing the whole movie.

Mr. Senensky – Your comments on costuming the extras reminded me of my experience being one of 300 extras in a scene for House of Cards for Netflix. Everyone came dressed formally so it shouldn’t have been a big deal but some of us were recostcumed with designer wear. The scene was of a presidential inauguration ball, and for some reason I’ll never understand they wanted me in a designer gown and close to the action with Kevin Spacey. I’ll never get why – I just had to walk around him – but they did want me in that gown. The big deal was that I am small (maybe they wanted me because you could see Spacey over me), the designer gown was made for a woman more than half a foot taller than I am, and we spent quite a lot of time hemming it up on me. David Fincher was the director – he was particular, rehearsed every camera angle six times before shooting it six times, and required 300+ people to be completely quiet on the set at all times. I walked around for five hours in a gown and dress shoes and when it was over I went home and drank a lot. You barely saw me in the final product.

6 times to rehearse! 6 times to shoot! Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm!!!