Filmed August 1977

Again with a nod to ALL ABOUT EVE’s Margo Channing:

Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy fight.

The day following completion of photography on THE GRANDCHILD I received the replacement script for my next assignment. Upon reading it I found it was a mixed bag of a jewel and crumbs. The jewel in the bag was that it was a fascinating story: a 101-year-old Indian returns to Walton’s Mountain, searching for the burial ground of his Cherokee tribe. He finds it is under the Walton barn. Who doe the land belong to? It was written by a relative of someone in the higher echelon of Lorimar Productions, and the crumb in the bag was that it was not well written. Happily I was not the only one who felt that way. Even more happily Earl Hamner said he would do the rewrite. The next three or four days I went every morning to his home and spent the day there as the script was totally rewritten from the opening to the final good-nights. Earl and I agreed that we wanted to create the character of Grandfather Joseph Teskigi as strong and poetic as the character Martha Corinne had been in THE PONY CART. Even as the script was being rewritten, I knew the actor I wanted to play him. Thirteen and a half years before I had worked with Eduard Franz when he played the older psychiatrist on the series, BREAKING POINT. He had played Indian characters several times in films, he had the face for our old man, he had the dignity, and he was a superb actor.

Our casting director, Pam Polifroni, was notified of our desire, and even before the rewrite was completed, Eduard Franz had been contracted to be THE WARRIOR.

When the rewriting was completed, Earl and I returned to the studio to receive some startling and disturbing news. Ralph Waite and Will Geer had announced they would not appear in the film unless a real Indian was cast in the role of the Grandfather. I was outraged and told Earl and producer Andy White that under those circumstances, I would like to withdraw from the project. I was reassured that what Ralph and Will were demanding was an impossibility; that I should stay aboard, conduct the necessary auditions and when we failed to find someone suitable, we would be able to continue with Eduard Franz playing the Indian Grandfather as we had planned. Now realize to be qualified to be considered an Indian, one did not have to be full-blooded. As I remember, having just one grandparent who was an Indian qualified an actor to be on the roster to be considered an Indian. There were a few fine actors on that list at the time, Victor Jory for one, but Pam Polifroni soon reported that none of them were available. I then began the task of interviewing the actors auditioning for this plum role. The parade was endless and most of them were in their twenties or barely out of them. But by then the entire incident had become a cause celebre. It no longer involved just the ultimatum from Waite and Geer. A contingent from the Indian acting community had contacted us; they were involved, demanding an Indian be cast, and there was no turning back. It was now too late for me to withdraw. A choice had to be made from the actors I had met. The only one who was old enough to assay the role of someone 101 years old was Jerado DeCordovier, a working extra in films. I have since learned he had some acting assignments, all small roles and not too many of them. There had been twelve speaking roles in the previous twenty-four years, and the last one of those had been eight years before. So after a difficult phone call to Eduard Franz to explain the situation, that’s where filming on this strange journey began.

The task before me was to stage and shoot the film as visually effective as it would have been if Eduard Franz had been playing the Indian Grandfather. I could count on those members of the Walton family who would be heavily involved in the story (Will Geer, Ralph Waite and twelve-year old Kami Cotler) to deliver their usual high quality performances, and I was pleased with the casting of Ernest Esparza III as Matthew, the Indian’s grandson; he had played one of the adopted children in my production two years before of THE FAMILY NOBODY WANTED. I knew going in that my problem would be Jerado. Although he was conscientious and dedicated to doing a good job,he was plainly out of his depth and just didn’t have the training or experience to play the complex, beautiful role that Earl had written.

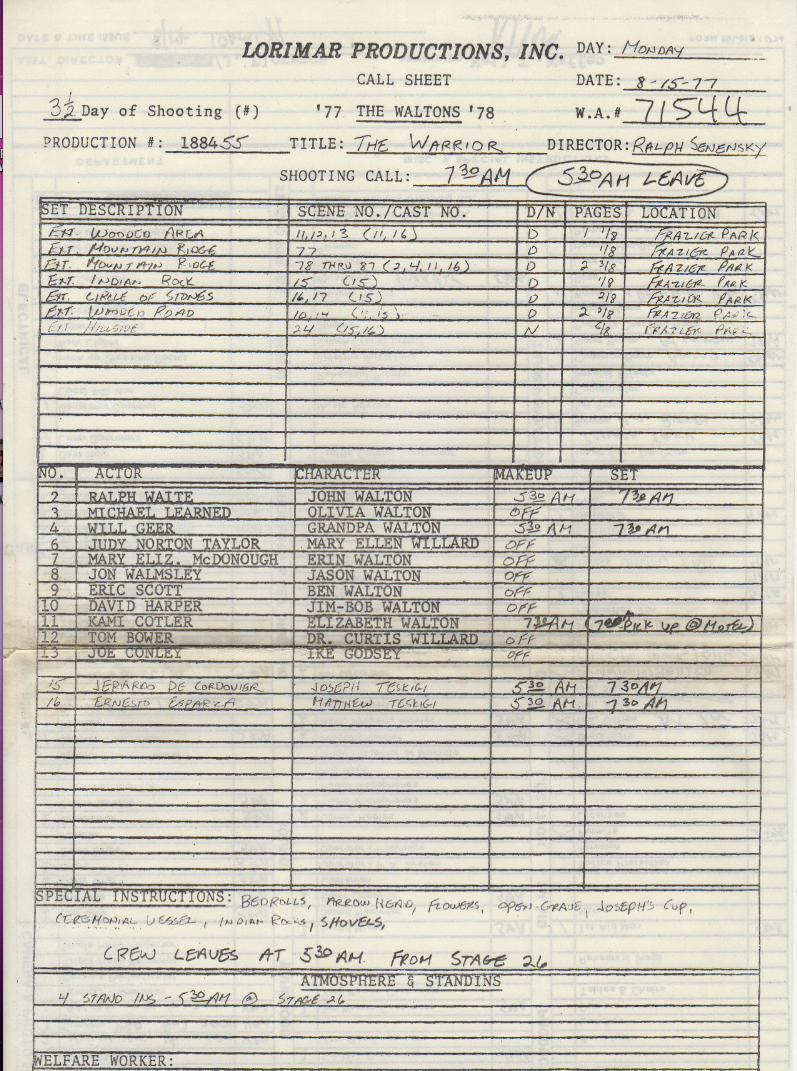

The opening barn sequences and the porch sequence (plus other later sequences) were completed the first two days of filming. On Monday, our third day of filming, we were to go to Frazier Park. Since we were scheduled to complete seven sequences totaling seven pages that day, we had a very early call. We left the Warner Bros. Studio at 5:30 am for our ninety-mile drive to Frazier Park, to be ready to shoot at 7:30 am. Note on the call sheet that Kami Cotler was to be picked up at 7:30 am at the motel close to Frazier Park where we had stayed during filming for THE CONFLICT. As a minor her hours on the set were etched in concrete, and if she had a 5:30 am call, we would have lost her mid-afternoon. So she and her mother were sent up to the motel the evening before, thus allowing her to have a later call Monday morning and allowing us to have her on the set for that additional two hours.

Earl wrote a beautiful scene between Grandpa and the Indian in which the Indian, once they sat down on a log to rest, had a one-page long speech where he spoke of his life. I had envisioned that scene as being played the way Beulah Bondi had poetically played the great final scene Earl had written for THE CONFLICT.

Eduard Franz could have delivered what I had envisioned; but Eduard was not on the mountainside with me, and that performance was beyond Jerado. His approach was that of a high school drama student portraying Shakespeare, arms wildly gesturing, pretentious orating. My job was to tone him down so he would simply talk to Will Geer.

Bringing Jerado down to that level was not without its humor. As I stated, he was not speaking to Will but was playing to the back row of that mountainside theatre. I said to him, “Jerado, just look at Will and talk to him.” Another take and again as his look left Will and his arm waved wildly, he shouted the lines to the hillside. Patiently I tried again. “Jerado, hold onto your staff, look at Will, and just quietly say the words.” I might add here I was given two cameras for the day’s work, so that if and when I got a satisfactory take, I would have both the two-shot favoring Grandfather Teskigi and his close-up. I’m not sure how many more times I had to repeat my plea before I finally said, “Jerado… just look at Will…say your lines quietly…and please…hold onto your staff, because if you don’t, I’m going to hit you over your (expletive) head with it.”

Since this was not being filmed on a feature film budget, there was no way that Earl could visually write into the script the sign Grandfather Teskigi would see in the mountains that would point him to the Indian Rock that would provide the final directions to the burial ground, then leaving it to the production designer to construct it. It was decided that when I scouted Frazier Park for our locations, I would look for something we could use. I saw that large arrow in the distance framed by two pine trees. It wasn’t perfect, but it sufficed.

I must admit my relationship to Ralph and Will during filming was not as warm and friendly as usual – no anger, just coolly professional. I do remember pointing out to Will there were other actors beside Indians who were being denied the opportunity to work, that older character actors also faced a limitation of job opportunities and with great competition for those roles that did come along. Will and Eduard Franz were both born in 1902. Eduard’s excellent series, BREAKING POINT, had not been a ratings success and had been cancelled at the end of its first season. THE WALTONS was in its sixth season.

I was always concerned when filming scenes involving fire. The special effects men in charge were wonderfully capable; the structures appearing to be on fire were not actually burning. Filming such a scene on a soundstage was especially frightening. I remember a big interior fire scene I directed at the old Columbia studio in Hollywood with drapes blazing that was really disturbing. There was some small comfort when a fire scene was being filmed outdoors.

In the short time we had to rewrite the script I did some limited research. I found a passage in one of the books describing an Indian legend. I showed it to Earl, who then wrote what I considered a lovely scene between the old Indian and young Elizabeth.

That sequence was shot on the final day of filming. In that scene Jerado’s performance came close to my original vision of the character of Grandfather Joseph Teskigi.

In the early fifties I had seen the national company production of SOUTH PACIFIC in Chicago. Richard Eastham had starred as Emile de Becque. A quarter of a century later he was presiding as the judge in the case of THE WARRIOR.

An unsung hero of this production was our film editor, Marge Fowler, who was married to our supervising film editor, Gene Fowler Jr. A little nepotism? I don’t think so. That awesome couple belonged to Hollywood royalty. Gene was the son of the great author, Gene Fowler, and Marge was the daughter of Nunnaly Johnson, esteemed screenplay writer of THE GRAPES OF WRATH, THE KEYS OF THE KINGDOM, THE THREE FACES OF EVE (which he also directed), HOW TO MARRY A MILLIONAIRE (which he also produced), his credits are endless.

When it came to the editing of the film, I don’t quite know where to start to explain the aberrant ways this production veered from the norm. Let me start with talking about double printing of takes. At Universal it was strictly forbidden. On one production there I was doing a scene with a difficult actor and had just finished take 11 without saying, “Cut, Print.” The assistant director told me the production department was concerned; when did I think I would reach a printable take? I replied that if I could print takes 4, 7 and 11, we could stop right now; by taking pieces from each of the three takes they would be able to edit the scene. The assistant director left me and called the production office. He was back in a few moments. “Print them.” Lorimar was not like that. And on this production they were aware of the problem cause by the position into which we had been forced. I was double printing, triple printing, quadruple printing, etc. constantly to deliver an acceptable performance on every one of Jerado’s speeches. And when you realize that many times I was running two cameras – that was a lot of printed film and unfortunately there was not the time for me to point out on each take, which speeches were to be used. Marge did that on her moviola and did it superbly. And she did something else. She used a more than normal amount of cutting away to reaction shots when the old Indian was speaking, masterfully improving the scene. I repeat what I said above: Marge Fowler was an unsung hero of this production.

I realized the disruption to this production was motivated by good intentions. The plight of employment for minorities in film (Black, Hispanic, Asian, Indian, even Women) was and is an ongoing problem, and it was a noble liberal stand that Ralph and Will took. But I defend my objection to their action as being a noble liberal opposition. When I started this project, I recalled my deep emotional reaction when I read BURY MY HEART AT WOUNDED KNEE, the chronicle of how American Indians were displaced as the U.S. expanded west. I remembered that I had to stop and put the book down when I finished a chapter. I was too emotionally disturbed to continue. Those were the feelings I wanted to impart to the future viewers of this film. I wanted them to see Joseph Teskigi as young Elizabeth had, “as real people — just like us.” I wanted them to empathize with the old man, to rejoice when he told of leaving the reservation that first time to meet his future bride and to share his pain when he told of the four thousand Indians who died on the “Trail of Tears.” The question then was, what was more important: a job for a single member of the minority or as vibrant and persuasive a production as possible to shine a bright light on the shameful but true story of what was done to this country’s original inhabitants.

I am left wondering. What if Robert Jacks had continued as producer of THE WALTONS. I’m positive Ralph Waite and Will Geer did not have cast-approval clauses in their contracts. As a no-nonsense, hands-on producer — what would have been his response to their ultimatum? Or what if Richard Thomas had not left and was still the star of the series. Would co-stars Ralph Waite and Will Geer even have broached the subject? As I said, I am left wondering.

The journey continues

Will and Ralph did not keep their objection secret. The crew knew. After Jerardo’s first day of filming, everyone was in a bit of shock. How right you had been. It was difficult. You say it in a gentle way by giving Marge the credit. I felt sorry for Jerardo – and you, Ralph. The multiple takes, and your patience with him — that I will never forget.

One other thing, I laughed out loud when Will was hammering the fence and said to Elizabeth, “You hold the nail — no, you hold the board I’ll hold the nail” an ad-lib, a wonderful moment —

There was also a moment between Elizabeth and Grandpa (in another episode) that was laugh out loud. It was Grandpa and Elizabeth outside the smokehouse. As they approached the door, Grandpa was to open it, Elizabeth to follow him in. There was a bent nail that held the door shut, and for some reason it was TOO bent. Now we’re rolling, and Will can not get the door opened — he fussed with it, tried his darndest, then finally turned to Elizabeth and said, “Who the hell bent this nail, Elizabeth?” That take, I believe, was printed. If it wasn’t it should have been. I’m sure Kami never forgot it. God Bless Will. I can’t imagine anyone else as Grandpa Walton.

The thing I never knew and always wondered about: who was the instigator, Ralph or Will? I do remember a wonderful moment after the fact. As a part of his contract to appear as John Walton, Ralph Waite had a deal with CBS to produce and direct a feature film. Our wonderful assistant director, Ralph Ferrin, was assigned to the project. Ralph told me that Waite was planning to use a non-union crew on the film and he (Ferrin) had said to him, “You mean you’re not going to use real Indians.”

Ha- ha – ha! I can hear Ferrin saying that. He was a great AD/Unit Manager and very kind to me.

It was Will who started the Indian brouhaha – Ralph Waite climbed aboard.

I thought that Jerado DeCordovier gave a beautiful performance in “The Warrior.” You may have had quite a time cooling him down, but in the end, it is a most powerful performance, particularly that scene with Elizabeth in the jail. Watching it again just now brought tears to my eyes. “Most tragically today, man does not always understand man.” How true.

I too thought the jail sequence was Jerardo’s best scene. I might add, if you check you will see that Kami has all the dialogue. Jerardo has one speech, the one you quoted.

I was pleasantly surprised to find this page when searching for information on Mr. DeCordovier. I’m only old enough to know the Waltons in reruns, but this has long been my favorite episode. In particular, I thought Mr. DeCordovier gave a fine performance in the jail scene, and Mr. Hamner’s narration at the end was just as poignant.

Thank you very much for posting this–fascinating to read more of the story behind one of my favorite episodes from television.

I have so many observations on this episode that I’ll have to do it in pieces.

At varietyultimate.com (Variety’s archive), I queried the word “jerado” for the year 1977 and it found two items (neither related to the casting controversy I was looking for). One was a full-page ad with five photos that began this way:

Oct. 12, 1977 The Glenn Shaw Agency proudly presents its client JERADO DE CORDOVIER Special Guest Star of “The Warrior” Episode “THE WALTONS” Tomorrow, Oct. 13 8 P.M. CBS-TV “.. . De Cordovier is a Man of a Thousand Characters, the Lon Chaney of the Space Age . . .”

***

I know, it’s the nature of show biz…:)

Small correction: your sub-title says it was filmed in October 1977, but I assume you meant to say August 1977. The 8/15/77 date on your call sheet would place me in Montreal on a family vacation, where I heard the news about Elvis dying the next day. My cousin announced the news, saying “he kicked the bucket”. I didn’t understand him – it was the first time I had ever heard that phrase before.

I give Jerado a passing grade in the final product of ‘The Warrior’. For the casting of “ethnic” roles, it’s sort of a gut reaction: either I buy it or I don’t. For instance, I watched the 1955 western ‘White Feather’, which had no real native-Americans among the Indian leads. Thumbs up to Eduard Franz (Chief Broken Hand) and Hugh O’Brien; thumbs down to Jeffrey Hunter and thumbs way down to Debra Paget.

BTW, the producer of ‘White Feather’ was Robert L. Jacks. Before reading your blog, I never heard of him before…had no idea he was producing movies in his 20s at 20th Century Fox. IMDB says he married the boss’ daughter, which explains a lot, but it’s obvious that he knew what he was doing then and much later. I assume you worked with him on ‘Eight is Enough’. He was only 60 when he died in 1987.

As usual Phil, regarding the date, you are correct again . It has now been corrected.

And to answer further, Robert Jacks was one of the FEW great producers with whom I worked. He produced the first four seasons of THE WALTONS. He produced the first six of the twelve Waltons I directed. I was told after his death that his favorite episode of those four seasons was THE MARATHON.

I remember how hard this episode was to film! Having worked on the show since I was 7, I didn’t have much patience for high ideals on set. I really thought the most important aspect of TV-making was getting it right quickly, so the scene could be printed and everyone could go home on time. I was aware that there had been a brouhaha about casting, but at 12 I didn’t really understand the reasons why a fuss had been made. And after years of working with so many talented professionals, I was super frustrated by the challenges this episode brought. I was also 12, which isn’t the most patient of ages!

It’s great fun to read what was really happening from a grownup’s perspective. Thanks for taking the time to put this together.

What’s remarkable to me, Kami, is to hear what you are saying about being impatient. The thing I have remembered is how patient 12-year old Elizabeth was in working with Jerardo,. The takes were endless, and on his close-ups you were beside the camera playing each take of each scene as if the camera was pointing at you. As I’ve stated above, my favorite scene is the jail scene. I truly believe the reason for Jerardo rising to heights he had not achieved before was because of your performance off camera.

Just watched this episode and you were wonderful in it. Brava, Kami!

Jimmy

I just found this blog & had to tell you how wonderful it is. I was a huge fan of the series when it ran & still love the reruns. I just saw The Firestorm again the other day & it is still so powerful–& so current! Thanks so much for writing your memories of working on the show. What an utter treat to read them!

Hello admin, i found this post on 21 spot in google’s search

results. I’m sure that your low rankings are caused by

high bounce rate. This is very important ranking factor.

One of the biggest reason for high bounce rate is due to visitors

hitting the back button. The higher your bounce rate the further down the search results your posts and pages will end up, so having reasonably low bounce rate is important for improving your rankings naturally.

There is very handy wp plugin which can help you. Just search in google for:

Seyiny’s Bounce Plugin

Yes, I vividly recall the challenges, I was there for THE WARRIOR – So

sad to lose Earl, but then he was so terribly ill – he’s writing

“Good-Nights” for the angels now – John or as Earl used to call me

“The Other John-Boy”.

Did they really expect us to what not notice uou were not Richard Thomas

This was so wonderful to read. I was doing a little research on this episode because I live near a Trail of Tears park and also grew up in Oklahoma. Beautiful to read your recollections. I’m enjoying watching through the seasons of The Waltons this spring and summer as I prepare for big changes in my life. I hope that life is wonderful for you. Thank you. 🙂

Thrilled to find this blog as I was impelled to find deeper info on the actor who played the Cherokee Elder.

Am reading The Hidden History of Guns, Thom Hartman. This book is a stunning wake-up call and to see this episode again one day after reading this book, seems providential.

I wish to thank all involved at every level. And to express my gratitude for the stunning legacy that this program carries as deep truths that touch the heart and spirit of all who are privileged to view any & all episodes: Gifts for the ages!!

Well, whatever everybody did, and I suspect you’re right to give the editor the major credit, in the end Mr. Decordovier’s performance seemed exceptional. I have watched part of the episode and have it paused at the beginning of the jail scene; all the commentary has made me anxious to watch the rest! Am very pleased to have found this blog; it is one of the only examples I’ve found of true “behind-the-scenes” exposition. The other one I’ve come across is Ken Levine’s excellent blog about his production of Cheers: http://kenlevine.blogspot.com/?m=1. I’ve just recently rediscovered The Waltons and despite seeing the episodes as a child, I seem to retain next to nothing of their content so it’s like seeing them virgin. They hold up remarkably well, even against the freer, exceptionally well-written shows of today, where humble TV fare is equal to the quality of the big screen. Kudos to all involved.

I think it’s great that both Waite and Geer had objections regarding the casting. Their strong feelings on the subject shows their passion and dedication to the series, to their craft and to Native Americans. I wholeheartedly agree with them. But I don’t believe however that Jerado DeCordovier was the right fit for the part.

Obviously we disagree. But not totally. You ended writing: But I don’t believe however that Jerardo DeCordovier was the right fit for the part. There we agree. If I had been able to keep the originally cast Eduard Franz in the part, the film would have been immeasurably more powerful and would have made a strong statement pro Indian.

Have enjoyed The Waltons my whole life. Very good stories of good moral views and family strength. I often wish I lived in such a family. This episode I do say Mr. DeCordovier may not have been a good fit but the jail scene with Elizabeth was good and touching. I’m watching it right now. Thanks for the memories!

Mr. Senensky – perhaps Mr. DeCordovier did not give you the performance you thought you would get with Mr. Franz, but it was nonetheless effective – you did a good job working with him. I’m curious about something – did you have a Cherokee advisor on the set? My husband worked on happily forgotten production called “Young Dan’l Boone” as an extra and reading wild lines – he studied with the Cherokee in NC to get the language and pronunciation right. If that short-lived production was able to come up with that assistance, wasn’t The Waltons able, or no? The reason I ask is that I thought the Waltons was set too far north for Cherokee country and perhaps having Grandfather come from a tribe more local to the Rockfish area would have been more authentic, but maybe I’m wrong about all that (and of course, during the Waltons era in Virginia, the tribes and Indians themselves were pretty much wiped out of existence by regulation – in Virginia there were whites and everyone else was colored, by legal fiat. If you were Indian, you were lumped in with negroes and tribes as a culture were pretty much ignored).

No, there was no Cherokee advisor on the set.

Thanks.

Pingback: SPECIAL: Why I Loved Directing The Waltons - Ralph's Cinema TrekRalph's Cinema Trek

Do you think there are times the production crew may have higher expectations than viewers? I find in my work as a copy editor that my audience does not always appreciate the “extra mile” I go to meet my own high standards, nor are they examining my work as closely as I am. I wonder if while a different actor in this episode might have meant a great deal to you as the director, having a less-experienced actor satisfied the audience well enough — they understood and appreciated the story, which is really all you want in the end. What do you think?

I do not believe in playing down to audiences. That way one loses those viewers with higher expectations of what they’r going to view and you can always hope that the taste of viewers with lower taste can be elevated.

I can understand that. Thinking back on the show, some aspects of Michael Learned’s performance still evoke my emotions through only subtle gestures — a half smile, a slight turn of the head, or even the angle at which she held her head. This must have been the product of training and years of experience; a less experienced actor would not know how to reach their audience this way, and the emotional connection would be weakened.

I think it goes further than that. A good actor, and Michael was certainly that, builds it from within.

Wow. You’re pretty sharp for 98.

I am surprised nobody mentioned how you shot the close ups in the jail scene. The old man appeared to be at peace with his situation while Elizabeth appeared sad and frustrated with her inability to do anything to help. I thought it was brilliant that you framed her between the bars of the cell (as if she were confined), but shot him as if he were less confined and uptight. Another very good episode. Thank you.

One of my favorite episodes of the entire series