FILMED June 1974

Film clip is from a recent interview by the Archive of American Television, a division of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation.

I was eager to meet Miss Bondi in person. As I’ve written before, it was the custom to hold a cast reading of the script before filming began. Since the script was too long to squeeze into the usual lunch-hour period, it was decided to hold the reading at 6:00 in the evening, at the end of the filming day. I brought up the possibility with producer Robert Jacks of including Miss Bondi in that reading. However, to book her for the reading would have meant her salary would start on that day. So I was assigned the task of calling her, telling her of the reading, and welcoming her to attend, if she so desired. She accepted the invitation most graciously. The scheduled evening arrived, and I went to Bob’s office, where a very large tray from the local Jewish delicatessen in Toluca Lake, owned and operated by Chinese, sat on a coffee table. Bob, with a disturbed look on his face, told me the reading was being postponed. There had had been conflicts in the schedules of Will Geer, Michael Learned and Ralph Waite. Only Richard Thomas and Ellen Corby were available. He had been notified of this too late to notify Beulah Bondi. She was on her way to the studio as we spoke. The others would be stopping by the office before leaving for their respective appointments. Have you ever attended a play in which a friend was acting and halfway through the first act knew it was the worst performance you had ever seen? And how you agonizingly spent the balance of the evening trying to figure what you were going to say to your friend after the curtain descended. Were you ever in a situation where you just wanted to wake up and find out it was all a bad dream? But when Beulah Bondi arrived, I knew it wasn’t a dream; I was wide-awake and the nightmare was going to have to play itself out. I introduced myself to her, addressing her as Miss Bondi. “Beulah,” she said. She was to be addressed as Beulah. I was surprised to see the towering mountain woman of TRAIL OF THE LONESOME PINE was barely five feet tall. Robert Jacks was there, Earl Hamner, Carol McKeand. Will arrived followed by Ralph Waite and Ellen Corby. Michael Learned would not be stopping by. Richard was still on the set filming. Introductions were made; Will and Beulah of course knew each other. As everyone took a seat, preparing for the reading that they all knew was not going to take place, Bob explained to Beulah the circumstances of the various conflicts in schedules, and that the reading would be postponed. Will interjected that his conflict that evening was that he was going to the opening at the Hartford Theatre of a play starring Henry Fonda in his acclaimed portrayal of Clarence Darrow. Beulah answered, yes, she knew about that. She had tickets for the opening, but she thought the reading was more important. You could have heard a marshmallow drop on thick carpet.

Later Will encouraged Beulah to tell us about Beulah Bondi’s famous summer gesture. Beulah told her story. It was in 1929 and she was playing Emma Jones in Elmer Rice’s STREET SCENE. Because it was a somber drama with a large cast and heavy sets, it didn’t have the budget for a pre-Broadway tryout tour. It was opening cold in New York, with just four or five preview performances. Beulah had worked out a piece of business, which she said she would have used if they had toured out-of-town. But she didn’t want to use it in the preview performances; she decided she would use it the night the play opened. So on opening night when that scene arrived, she was seated on the steps of a New York brownstone tenement set. It was hot and she had a folded newspaper which she used to fan herself – her face, neck, under her arms, all the while carrying on a conversation with a character leaning out of one of the tenement windows. At one point she was to stand and turn upstage to look up at the woman in the window. As she rose and turned, she reached behind and with a firm grip pulled at her skirt and her underwear beneath it? And there was this roar of laughter from the theatre. And it went on and on and on. She stood there frozen, waiting for the laughter to subside. But it didn’t. It grew. It stopped the show. Finally, it finally did end and the play continued.. After the show, Elmer Rice, who had directed his own play, came backstage to her dressing room. She was expecting to be fired, but he told her to keep the business in her performance. STREET SCENE was the show that brought Beulah to Hollywood in Samuel Goldwyn’s 1931 production, directed by King Vidor. The bit of business was retained in the movie. But Beulah was not happy with the way Mr. Vidor handled it. He had a low camera angle shot of her rear end, so that her famous summer gesture was blown up for the world to see in startling close-up.

THE CONFLICT, being a two-hour show, should have had at least a thirteen-day shooting schedule. But Hollywood was facing the possibility of an industry strike; I forget whether it was writers or actors. I was scheduled to start filming on a Friday, which allowed just twelve days to complete the film. The following week we were to film on location in Frazier Park, an area ninety miles north of Los Angeles. Location shooting allowed for a six-day week. Then we would return to the studio for an additional five-day week of filming before the possible closing down because of a strike. But one more snag hit the fan. The production filming ahead of me was running behind. It also had to be finished before the possible strike. I ended up beginning my show at 2:00pm on Friday, which meant I had to complete this epic in eleven and a half days.

THE CONFLICT, a two hour script beautifully written by Jeb Rosebrook, was a story set in the 1930’s, but it read like a frontier drama peopled by real pioneers, a project that seemed more like a western, but a western without horses and Indians. It was like turning the clock back an additional century.

Casting director Pam Polifroni brought in a very long line of young actors to audition for the role of Wade, Martha Corinne’s great grandson. I remember that NIck Nolte impressed us enough that I went to see him in a production of PICNIC at one of Hollywood’s small theatres. The following day Richard Hatch came in to meet us. I remember that he didn’t just sit and read; he moved all over the office. He gave a dynamic reading. After he left Bob Jacks looked at me and said, “That’s it!” I couldn’t have agreed more.

Robert Jacks told me he would have liked to have taken us to Jackson, Wyoming, where they had filmed THE HOMECOMING, the television movie that spawned the series, but lack of budget made that an impossibility. Since the requirements of the script were too demanding to be filmed on the Warner Bros. backlot, it was decided that we would do a six-day location at Frazier Park, California, about ninety miles north of Los Angeles. Ed Graves, the art director, went to Frazier Park, selected the site where Martha Corinne’s house would be situated, designed and had the house constructed and then dressed the surrounding area. The house of course was a façade; the interior would be filmed back at the studio on a soundstage. The company was booked to stay at The Caravan Motor Inn in Gorman, California, as I remember about a twenty minute ride to where we would be filming.

On our arrival at Frazier Park on Monday morning I went to our make-up people with a plan. Richard Thomas has a very visible gray birthmark on his left cheek. In order to establish a mood of solidarity in the company and also provide a bit of humor to get the location off to a happy start, I asked that they apply a gray birthmark to the left cheek of every member of the cast and crew. When Richard arrived on the set to film the family’s arrival, he was amazed to find a plethora of potential siblings.

As we were leaving Los Angeles that Monday morning, I was informed that Kami Cotler (Elizabeth) was ill and would not be working that day. I had no recourse but to go ahead and film the family’s arrival without her. When she returned I filmed a shot of her to be inserted where needed.

On location there was a long, long trailer called a honey wagon with several small dressing rooms for the stars. At the end of our first day of shooting, as we prepared to drive back to the motel where we were staying (about twenty miles), Beulah told me she had left her script in her dressing room. I immediately became concerned with getting it before the honey wagon left. Beulah then assured me it was no great catastrophe; she knew her scenes for the next day. What I finally learned was Beulah knew all of her scenes for the entire picture.

The morning we prepared to shoot the sequence with Martha Corinne’s feisty pigs, Judy (Mary Ellen) informed me that her character wouldn’t behave as written; she wouldn’t be frightened, wouldn’t run away and climb a tree. I had already been down that road of script being rewritten on set and didn’t plan to go down it again. Fortunately Bob Jacks was at the location with us, so I sent out an SOS, he arrived at our filming site, had a short meeting with Judy, who suddenly saw the light and was properly terrified of pigs..

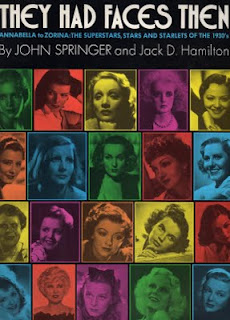

Soon after we commenced filming, Beulah told me there was a book coming out soon dedicated to her. The book was THEY HAD FACES THEN by John Springer.

It is a magnificent book that includes mini bios of every actress who had an English-speaking role in any film released in the 1930’s.

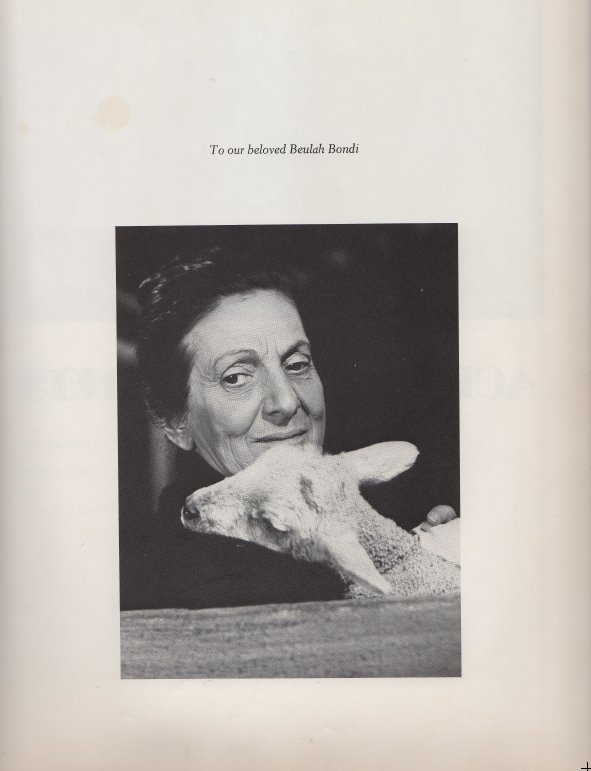

John Springer wrote in this book: “When you are speaking of the most moving movie scenes of all times, certainly you’re going to choose several from Leo McCarey’s MAKE WAY FOR TOMORROW. There’s the heartbreaking final moment when the old man is going away and the old lady is at the train station to see him off. He doesn’t know — but she does, and you do — that they will never see each other again. …There is the absolutely devastating scene when the old lady gets a telephone call from her husband so many miles away — and pours out her love and loneliness to him, oblivious of the annoyed, then ashamed, then strangely touched guests at a card party in the room where she is on the phone. Try to see that without choking up.

“I yield to no one in admiration for Victor Moore, but the person who tore you apart at all of those moments was the beloved Beulah Bondi, surely the most versatile character actress on all levels the movies have known. She wasn’t one of those darling lavender-and-old-lace ladies. Her Lucy Cooper in MAKE WAY FOR TOMORROW could be a cranky, cantankerous old girl. But she was so real, she was frightening. Academy Oscars ceased to have their full value the year she did not get a nomination for MAKE WAY FOR TOMORROW.”

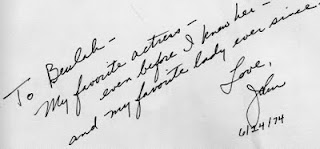

I today have Beulah’s copy of Springer’s book with the following inscription

That scene talking about the government was written 48 years ago about a time 40 years before that. And it still sounds contemporary!

The exterior night sequence was filmed day for night. To have filmed it at night in those woods would have been prohibitively time consuming and expensive. I was and am in awe of masters of their craft like director of photography Russell Metty.

The scene of Grandpa and Boone fishing was not filmed at Frazier Park. It was filmed on the backlot after we returned to the Warner Bros. Studio.

Beulah told me about her experience on the movie, THE SNAKE PIT, starring Olivia de Havilland and directed by Anatole Litvak. The movie was well into production by the time she reported to the studio. She was greeted with dire reports from other character actresses who had been working. They told her that Litvak was impossible, overly demanding; nothing any of them did seemed to please him. Beulah responded she couldn’t understand that; she had worked for ‘Toley’ before (THE SISTERS with Bette Davis at Warner Bros.), and she had never had any problem with him. She was warned, just wait, you’ll see. So came time for Beulah’s first scene. She reported to the set in make-up and costume, was greeted by Mr. Litvak, did a brief rehearsal and then prepared to film. Camera rolled, action was called, and Beulah did her scene. Litvak called “Cut, let’s do it again, please.” The warning actresses on the side lines gave Beulah nods of the head that said, “See, what did we tell you?” Beulah did take 2. Again “Cut, let’s do it again please.” More nodding heads and smirks. Take 3. Take 4. Take 5 and finally “Cut, Print.”

Beulah, never a shy one (she was a Taurus) went up to Litvak. “Toley, may I ask you a question?”

Litvak: Of course, Beulah. What is it?

Beulah: You never said, so what was wrong with those earlier takes?

Litvak: Nothing, Beulah. I just like to watch you act.

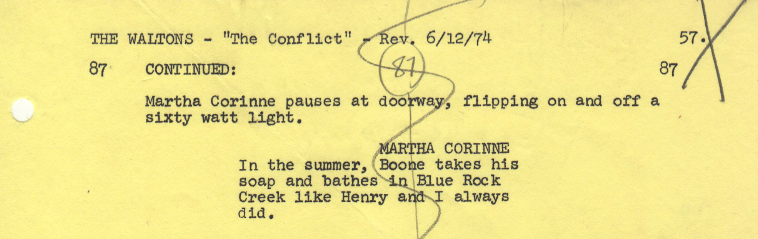

Beulah was meticulous in her preparation, not only in having the entire script learned, but in the detail of the business she planned to do. There was a moment in the scene when she visited the new house that illustrates this point.

She milked that single line of stage direction for twenty-three seconds of screen time.

I once asked Beulah how aware she was of the camera as she acted, how much she played to the camera. She said not at all, but I privately wondered if there was an instinctive awareness then, a connection to the big black box. How else to explain the perfection and the beauty of the portrait she presented in the final close-up that ended the previous scene.

To be continued

Just a quick note, off topic from this show. I hope you will be looking back at some of the episodes of “Insight.” As I have written to you previously they had a big affect on me as a high school student.

Please add me to your mailings.

Done! Welcome!

Earlier this month, the INSP channel had a marathon of Earl’s favorite episodes, which included his commentary. I saw very little of it, but ‘Grandma Comes Home’ and ‘The Conflict’ were two of them.

A few words about your other distinguished guest stars:

Even in the “darkness”, I immediately pegged that voice in the 8th video – Mills Watson, who specialized in playing second-tier punks in the ‘70s. Then he turned that experience in a comedic direction as Claude Akins’ idiot deputy in the Sheriff Lobo programs.

Morgan Woodward’s NINETEEN appearances on ‘Gunsmoke’ included playing an ignorant mountain man on occasion, so the role of Boone was right up his alley.

Lastly, you had Paul Fix whose career stretched back into the Silent Era. For me, he’ll always be the old Indian chief who said “Shut your mouth, little man!” to Dr. Loveless (Michael Dunn) in ‘The Wild Wild West’.

Hello again. Two things strike me in this post. One is the way that Martha Corinne’s face falls back into shadow after seeing her reflection in the mirror. That’s brilliant! The second is the light switch scene. I really love how Miss Bondi’s beautiful face lights up when she’s turning the lights, coupled with the way she looks sad and confused when she turns it off. I can totally believe that this is her first experience with electric lights. Wonderful actress!

And all of that was preplanned by Beulah. That was what she meant when I asked her a week or so before we began filming THE PONY CART if she knew her lines yet, and she responded, I’ll know them by Thursday. THAT’S WHEN THE WORK BEGINS.

What a joy it is to find this blog, I grew up with The Waltons and now my children are enjoying this wonderful series. The Conflict is without doubt my favourite episode, there is so much in the two instalments that says everything about family, heritage, govt and progress and how the two latter so often affected the two former. I always enjoy the ice-cream-making scene where the family all gather to make ice-cream out of Martha-Corinne’s blackberries….it looks very authentic using the old churning equipment – did they really go through the process of making the ice-cream for this scene?

The scene where the Walton family first arrive at Martha-Corinne’s house and she is seated beside Boone standing; Beulah is so tiny but in that scene she conveys the same impact that Burl Ives made in ‘The Big Country’ in that famous moment when he throws the door open on the ballroom scene and confronts his rival Charles Bickford. Both Beulah and Burl Ives do very little in the way of action, the power comes from their sheer immobility and presence. That’s what I get when I see Martha-Corinne for the first time in The Conflict and it gets you right in the gut.

Welcome Wendy! Regarding making the ice cream, I truly don’t remember. My suspicion would be that considering the effectiveness of the crew, we did make it Whether or not we ATE it is another story.

I love your comments about Beulah and her presence. When I read the script, my first and only choice for the role of Martha was Beulah Bondi. I remembered her for many roles, but mainly the mother in THE TRAIL OF THE LONESOME PINE, which I saw when I was a teenager. The thing I remembered was the tall, imposing figure she emitted from the screen. Imagine my surprise when I met her in person, and she was barely five feet tall.

Ralph, I think only Beulah could have played that role – she had the right combination of tough, grit and almost vulnerability. But we all know that there was nothing vulnerable about Martha-Corinne except where her need for Henry in her darkest hour was concerned – and she showed that in the graveyard scene which was truly touching. It is amazing how the camera can capture the essence of a person and magnify it, Beulah might have been less than five feet tall in person but in every other respect she was ten feet tall and thanks to the magic of film we are able to believe that.

I found this post after watching the 1st part of this episode, after querying whether Ms. Bondi had won an emmy for the performance. What an amazing actor! As you point out, the theme is very much contemporary. I’m slowly making my way through all the episodes of this show, which I initially watched in the seventies. The streaming quality is awful via amazon prime, but I’m so appreciating it. I’m a mental health counselor and after work The Waltons helps renew my spirit.