FILMED November 1970

Five months after fighting the sands of Point Dume I was still bouncing back and forth between sit-coms and drama. The comedy bookends were NANNY AND THE PROFESSOR and THE PARTRIDGE FAMILY; the dramas in the middle were a new series back at QM Productions, DAN AUGUST starring Burt Reynolds. Starting in September, 1970, I found myself back at the Goldwyn Studios on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood where six years before I had filmed THE FUGITIVE. And I found that many things had changed.

DEAD WITNESS TO A KILLING was the third DAN AUGUST episode I directed and like many conflicted series in its freshman year, it was still searching for its identity. In retrospect one of the most astounding bits of advice given to me by a producer was what Tony Spinner said to me when I directed my first episode: “Watch Burt Reynolds. He’s going to try to insert charming bits of business into his role and the one thing the guy doesn’t have is charm.” More about that later.

Seven years earlier in 1963 I worked with then twenty-three year old Martin Sheen for the first time. I had recently been impressed with a stunning performance he gave in a leading role on THE DEFENDERS, so that when casting director Lyn Stallmaster suggested him for a minor role in an episode of THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH, I said, ”He wouldn’t do that, the part is too small.” Lyn replied that Martin was new to the west coast and wanted to work. I had since cast him in an episode of INSIGHT and the leading role in the recently discussed MATT LINCOLN. When casting director Tom Palmer suggested Martin for the cab driver in this DAN AUGUST episode, my response was an echo of my earlier response. I thought the role was a supporting role, the least important of the three male roles in the show and that Martin was now at a point to accept only leading roles. Again I heard, “He wants to work.”

THE BOYS IN THE BAND had recently been released. Besides being a brilliant film it was a gold mine when it came to casting. Quinn Martin was always amenable to finding new talent and he was not averse to the added expense of importing New York actors; he was willing to pay the required round trip airfare and the per diem during their stay on the west coast. Laurence Luckinbill had been very impressive in the film and he was the first of several in that cast that I would be directing.

I don’t remember whether I was aware of Monte Markham through viewing his work or whether I accepted him on the recommendation of executive casting director John Conwell and casting director Tom Palmer. Tom like John was an actor converted to casting director. As a young man he had been a member of the Alfred Lunt-Lynn Fontanne theatre company on Broadway. Tom was a close personal friend and I loved the tales he told of working with the Lunts, of hearing that whenever they returned to the west coast, they always made a point to have dinner with their “Tommy”.

Quinn Martin had been a sound editor before he became a producer. He was a bulldog when it came to matters of sound. When filming close-up coverage of a scene overlaps were absolutely verboten. (Overlaps were when the voice of the actor off-camera extended over the voice of the speaker being filmed.) I liked having actors overlap, so when doing coverage I found that if I filmed tight over-shoulder close-ups (with both actors on film) in place of individual close-ups, I could overlap with impunity. Quinn also had a rule that whenever a scene was an interior at a new location, an establishing shot of the exterior of the building of that location must be used. I faced a problem when wanting to do a shot that was a collision of his two fiats. I wanted to do an establishing shot of a coffee shop seeing three people seated at a table through the large plate glass window and I wanted the dialogue to begin in that shot. The soundman refused to do it. His reason was that the voices would not be realistically heard under those conditions. I persisted, insisted and won. There were no repercussions when the film was viewed the following day.

Our fourth day of filming was like a road trip. Our final destination was Oxnard, a small city north of Los Angeles that was used as the community where Dan August was a member of the police department. En route we were scheduled to film a sequence at a tennis club, and then on to Oxnard for some sequences at a boarding school, a cemetery and the exterior of the police headquarters. I scouted the locations on a bright fall sunny day and planned my staging and camera coverage. When we left Los Angeles early Thursday morning the weather forecast was a threat of rain. It was decided to ignore the threat and pray a lot as we traveled north. I had planned to film the confrontation between Frank and his son in a garden at our boarding school location. By the time we got to that scene, the weather forecaster had been proven right and that was no longer possible.

As we started rehearsing the father-son confrontation, the mother of Radames Pera, who was playing son Cort, came into the room and called me aside. She whispered to me, “If you need to make him cry, I know how to do that.” I was outraged. Very quietly but strongly I said, “Get out of here.”

The scene between Dan and Cort, which came later in the film but was shot earlier, was also planned to be done in the garden. Because the rain held off, that was where we did it.

By this time the latest Mitchell cameras accommodated a zoom lens. The amazing thing was how important that seemed to be to the press. The previous year I remember a reporter for TV Guide, who was doing a cover story on THE COURTSHIP OF EDDIE’S FATHER, being on the set and questioning me not about the stories, not about Bill Bixby or Brandon Cruz. Her questions were about the zoom lens; what did I think of it; how was I using it. As I look back now, my answer should have been, “Excessively.”

I was and am still amazed that the Quinn Martin Production organization that in its earliest years had the superlative Meredith Nicholson and William Spencer as directors of photography (THE FUGITIVE, 12 O’CLOCK HIGH and THE FBI) was so unaware of the drop in quality of the photography for this series. I liked cameraman Ben Colman. He was a fun guy. But as my cameraman he drove me slightly crazy. Early mornings I would be ready to stage the first scene so he could see what he would be lighting and I would have to wait because he was already lighting the entire set. One day we were filming at a deserted hotel in Hollywood. It was winter, there was no heat in the hotel and it was cold. I remember I wore my overcoat all day inside the building. I had given Ben a set-up in the bar. It was a simple, confined over the shoulder shot across a person at the bar to the bar tender. I was sitting in the lobby when one of the stand-ins came to me and said, “Didn’t you do a simple shot at the bar?” When I responded that I had, he went on, “I think you’d better go check it out. Ben’s lighting the whole room.” Exteriors were even more difficult. Ben didn’t want to use the large arc lights that were the norm. He had a company that rented lighting equipment to film companies and those were the instruments he was renting to QM. They were not large; they were in fact very small; I thought they looked like wired coffee cans. As a result lighting an exterior night shot took a very long time. The last sequence on the third day of filming was the exterior and interior of a garage in Santa Monica. Ben took so long to light the taxi’s approach and entry into the garage that a wrap was called and the interior was rescheduled to be filmed later at a different location. I called my agent. Facing another day of location filming, three more days of interiors at the studio plus having to go off the lot to pick up the scene we were currently dropping, I could not see me starting to prep a new show just a week away. I asked that he get me out of that next assignment that started the day after this show finished.

The young doctor was twenty-three year old Stephen Collins in an appearance so early in his career it is not listed as a credit on his IMDB filmography. And it was a long career. Appearances in both feature films and television, a regular on six different television series. And he’s still working!

The first stop on that fourth day of location filming was to be a tennis court in Calabasas, but by the time we arrived there it was already raining. That was my first restaging of the day as I moved the scene to an interior of the clubhouse.

I wrote in GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DRIVE that I met Milt Kamen in 1964 when he auditioned for THE JACK IS HIGH on SUSPENSE THEATRE. He lost that role to Larry Storch. The first time I cast him was in this episode. I had been impressed with his audition. Milt had been a regular on CAESAR’S HOUR, the Sid Caesar comedy series. He was basically a comic, but like most comics, he was also a fine dramatic actor.

Banner’s run through the streets was in San Pedro, a city south of Los Angeles, as was the interior of the bar, Logan’s Place.

In 1963 I faced a firestorm named Dorothy Brown at ABC because of THE BULL ROARER, the show that for the first time said the word, “homosexual” in a network drama. The show itself was the story of a boy fearful that he was gay, but proven not to be. Seven years later the subject was approached more head-on and there were no firestorms.

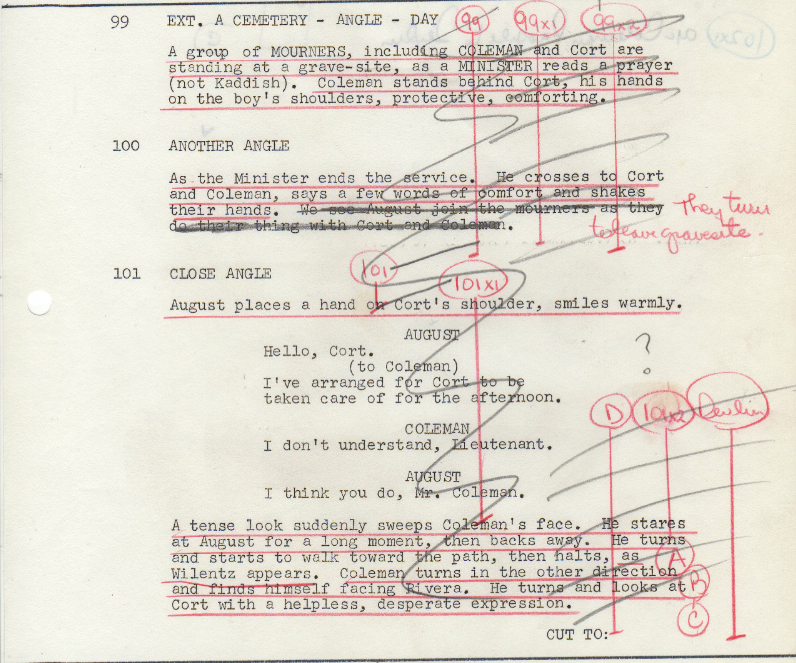

The third location on that fourth day that ended in Oxnard was a cemetery.

While we were preparing to film the scene at the boy’s boarding school between Devlin and his son, we had a call from Howard Alston, executive production manager for QM Productions. He said that we should stop what we were doing and go to our cemetery location. The plan was we could do the father-son scene later at a set at the studio so it was more important to film the cemetery scene at the location. I don’t remember how I knew there was a chapel at the location where we were. I suggested to Howard that it would be better to finish the father-son scene, and instead of moving to the cemetery I would film that scene in the chapel. He agreed. Another scene revised on its way from script page to film. And incidentally accomplished in one set-up instead of eight.

Our final scene on that fourth day when nothing had been filmed as planned was at the exterior of the police department in Oxnard. That one scene went onto film just as it was laid out in my script.

It had so many plus factors in its favor, why did DAN AUGUST fail as a series? The show was a QM Production, created with the same high production values that had contributed to the success of THE FUGITIVE, 12 O’CLOCK HIGH and THE FBI. Burt Reynolds was a superstar waiting to light up. The year following DAN AUGUST’s cancellation he starred in DELIVERANCE on the big screen and made an appearance on Johnny Carson’s show that revealed the boy HAD CHARM. And his dedication to making DAN AUGUST a success was relentless. Burt was an accomplished stuntman and did all of his own stunts. He would wave his rights under the Screen Actors Guild contract to a twelve-hour turnaround if it would help the schedule. I saw him work an arduous week of location filming and leave on a midnight flight on Friday for some spot around the country to make a personal appearance. I repeat my statement: It had so many plus factors in its favor, why did DAN AUGUST fail as a series?

The journey continues

Great show as always Ralph — and I believe I have an answer to your question “..why did Dan August fail as a series?” — you already touched on it.

Michael Eisner was in programming at ABC at the time and partially responsible for the cancellation of the series. Here’s a quote from Michael’s interview for the Archive of American Television —

“We had a show called Dan August when I was at ABC, and it failed, and it starred Burt Reynolds – it was a typical action show, Quinn Martin, but it was pretty good, it was fine — but didn’t do well, and we cancelled it on like a Tuesday and I was at home, I don’t know, like a few nights later, watching The Tonight Show when Burt Reynolds shows up and he is hysterically funny, self-deprecating, I mean just hysterical — and I call up Quinn Martin and I said “Where WAS this guy!?” If we had just known that this man had this sense of humor Dan August would have been a different Dan August.”

Having known Burt personally and professionally I can say, without hesitation, Burt had a fixation on Brando and it took years to move him away from that – his ‘Dan August’, to me, looks like his ‘Brando’ — it’s a shame it wasn’t the bright, witty, smart, funny, sensitive and sweet guy Burt was in life at the time — that guy would have been sensational.

With so much going for it, how did it fail? You neglect to take into account the so-called taste of the American viewing public. Remember how, for years, Seinfeld was considered the summum of comedy? And you wonder why genuinely good shows fail?

Burt never got a decent chance with this series. Had this aired on any other network except All the Best shows Cancelled (ABC), then it would have taken off. The sad thing is it never got a good run in Syndication either like some other shows and if it had I am confident it would garnered a larger fan base. Burt did do other TV shows: Riverboat , on NBC; Gunsmoke on CBS; Hawk on ABC and Evening Shade on CBS; and BL Stryker of course. Dan August I feel was his best work and deserves a DVD release or at the least a syndication comeback. I for one never cared for that fun-boy stuff with the likes of Smokey and the Bandit and others. I thought his dramatic roles, this included, were his best work.

Wonderful article.Glad I came across it.Why no Dan August on dvd??Any suggestions out there on where we can apply some constructive pressure?

My first TV performance! It was my first journey to LA and I was working at the Ahmanson Theatre as part of a national tour of the Broadway hit, “Forty Carats,” opposite Barbara Rush, who would later play my mother on “7th Heaven.” I joined Screen Actors Guild with my “Dan August” appearance. I don’t think I ever saw it, so I had no recollection that Martin Sheen was a guest star. Thanks for posting this!

And I’m sorry we never got to work together again. You’ve had an admirable career and I’m happy to having served as a stepping stone.

Superb Commentary! I was fascinated by the gay issue, and I felt it was very daring for the 1970’s. The ending was a surprise! The very first time I saw Martin Sheen in a CANNON episode, I said he looked like James Dean. I really enjoyed the scene in Logan’s bar. I think the terrific actor who played Logan was William Marshall. He went on to movie fame as BLACULA. Am I correct, Ralph?

Sorry Kathy, you are not correct. It was not William Marshall. Logan was played by Rozelle Gayle, and I agree with you, it was a delicious performance.

I recently flipped through Burt’s autobiography at the library. Unfortunately, it devotes only about one page to ‘Dan August’ – almost all of it related to how he got the job.

He went to Quinn Martin looking for a project he could star in…anything BUT a cop show (he thought QM’s cops were like Jack Webb). Naturally, QM pitches ‘Dan August’ at him, which prompted this exchange:

Burt: He’s a no b.s. cop…he’s not funny.

QM: You’re not funny.

QM was referring to the Dan August character – that’s how he wanted it. He thought women would love Burt in this role.

Burt still resisted, so QM asked him, “Who do you think is the highest paid actor in TV?” Burt didn’t know and took a stab: “Maybe one of the ‘Bonanza’ boys, Michael Landon.” QM talked to someone on the phone, hung up and said, “Landon is getting $25,000 per week. You’ll get $26,000 per week.”

I can’t believe the figures he wrote. When someone says “per week”, I assume that equates to “per episode.” Yikes! I guess a series like this could not afford low or middling ratings.

Pingback: SPECIAL: Black Lives Matter - Ralph's Cinema TrekRalph's Cinema Trek