FILMED November 1967

As I wrote earlier, Googling my name on the internet could leave readers thinking that I directed my seven outings on STAR TREK in a compact ninety days rather than spread out over the twenty months it actually took. The facts are that in that span of time I actually returned to Planet Earth several times to work on other shows and on my visit after filming OBSESSION in outer space, I landed at Universal Studio in Universal City to helm an episode of what had already been acclaimed one of the successes of the new season, IRONSIDE, starring a wheelchair-bound version of Perry Mason in the rotund body of Raymond Burr.

Although this was the ninth production I directed for Universal (including a couple when the MCA talent agency first purchased Revue Productions and released their product under the Revue Productions banner) let’s get something clear right off the bat. I didn’t like working there. MGM, the Bert Leonard group at Columbia, Desilu, all had a familial feeling about them. Universal was a factory. I used to say that as I drove through the gates onto the lot, I felt as though I passed through electronic beams that sought to drain the creativity out of me. And now that I’ve said that, I want to add that directing GIRL IN THE NIGHT was a very pleasant experience.

The script was written by True Boardman, an actor turned writer with an impressive background. True’s father was a silent film star and True, as a youngster six or seven years old, had also acted in film. He even made a film with Charlie Chaplin. I didn’t meet True until some time after completing this project, but we became friends and I would often play bridge with True and his wife. Thirty-five years later when I left Los Angeles and moved to Carmel, I discovered that True lived on the Monterey Peninsula. Our friendship reignited and we ended up forming a Hollywood ex-patriot group that met every other Tuesday for lunch. The group included the two of us, Lamont Johnson, Don Hanmer, Shan Sayles and Kit Parker (a local film distributor who actually was the instigator for forming the group). I have to tell you a favorite story. One lunch, after we had been meeting for several years, I arrived anxious to tell them that I had had a pacemaker installed since we had last met. True looked at me disdainfully and said, “I’m on my fourth.”

Tisha Sterling, a Universal contract player and the daughter of Robert Sterling (I had directed Sterling in a TWILIGHT ZONE and a NAKED CITY), was cast as Elaine. I faintly remember meeting Tisha concerning the portrait of her that would have to be painted. And then I was notified that Tisha was out. She had been cast in a major feature film, COOGAN’S BLUFF, and Susan Saint James, another contract player, would be our Elaine. At Universal I found I was very rarely consulted about casting. In this case I was notified another contract player, Steve Carlson, was set to play Johnny, and the rest of the cast would include Donnelly Rhodes, Oscar Beregi, Mort Mills and Simon Scott.

But before that scene or any other scene could be filmed, I encountered the kind of incident that seemed to occur more often at Universal than at other studios. I left the studio Wednesday, late afternoon of my last day of prep, prepared to commence filming the following morning. Soon after I arrived home, I received a phone call from producer Cy Chermak. He told me I was to report to the studio the following morning as scheduled, but I would not be filming. This gets interestingly complicated. You know, eons ago George Washington was not in favor of political parties. He felt politicians would find that their allegiance would be to their party, not the government they were supposed to serve. (And hasn’t that come true!) Universal wanted the various crew people’s allegiance to be to their studio department, not to the production to which they might be assigned. So NO SHOW HAD A PERMANENT CREW. Each department (Camera, Gaffers, Grips, Props, Make-up, Hair, Wardrobe, Script) had its crew units. When a unit finished an assignment, it went to the bottom of its department’s crew list. As each new production started, the unit at the top of the list would be assigned. That way no one on any crew ever worked on any one show long enough to form an emotional attachment to it. Raymond Burr was not happy with this arrangement. He wanted to have a set crew. He wanted to have the same make-up person, the same hairdresser. He wanted exactly what the studio didn’t want. He wanted a team like he had had on PERRY MASON. He had complained. The Black Tower had acknowledged his complaints, but nothing changed. So Cy told me to come to the studio prepared to shoot, but there would be no filming because Ray would not be showing up. He had a scheduled meeting with the black suits in the Black Tower the next afternoon to resolve this problem, once and for all. I don’t know what happened at that meeting. I’m sure the black suits said, “No problem, anything you want, Ray baby.” But I know that I reported at 7:30 am on Thursday morning, by 8:00 am I was back home. I reported again at 7:30 am on Friday morning and filming commenced.

Producer Cy Chermak told me that GIRL IN THE NIGHT was a remake of a 1963 episode of THE VIRGINIAN written by Dean Riesner, A PORTRAIT OF MARIE VALONNE. Thus the split screen credit: Teleplay by True Boardman, Story by Dean Riesner.

Cop shows, and by this time after my association with NAKED CITY, ARREST AND TRIAL and THE FBI I was well indoctrinated into the format, presented the problem of making the scenes interesting that involved police questioning people about the crime that had been committed. After all those scenes were mainly questions and answers, exposition. This show was different. One of the people involved in the case was Ed Brown, the victim in the crime and a cop on Ironside’s team and his response, which was firsthand knowledge, was presented in flashback. This later led to three other people being questioned, all of whose information was also presented in flashback. This show provided another first for me; it was the first time I directed a production using flashbacks to tell its story.

True Boardman in adapting THE VIRGINIAN western script to a modern cop story turned it into what I considered film noir. And film noir demands a good cinematographer and that I had with the assigning of Lionel Lindon to this project. This was not the first time I had worked with him.

Raymond Burr had had a long association with Gilmor Brown and the Pasadena Playhouse. Not only had I graduated from the school at the Playhouse in 1948, between 1955 and 1958 I had directed six productions in Mr. Brown’s personal theatre, the Playbox. I assumed this might be some sort of bonding between Burr and me. He was respectful of it when I told him, but Ray was a cool, aloof man, at least as far as my association with him, very professional, but very impersonal.

Which leads to another first for me – filming a character lip-sync singing to a pre-recorded playback; in this case the playback was of another singer’s recording. But mine was not the most difficult part of this process. There was someone from the music department on the set when we filmed to help me check that Susan’s mouthing of the words matched the sound track. It was Susan’s responsibility to do it. She had been given a copy of the recording when she was cast and lip-syncing to that recording for this one short sequence had been a large part of her preparation.

One day I was talking to some of the cast and I told them that our script was a rewrite of an episode of THE VIRGINIAN. Oscar Beregi, who was cast as Stefan, smiled and said, “Yes, I know, I was in that production.”

“Oh,” I replied, “what role did you play?”

Still smiling, Oscar said, “The same one.”

Oops! That was one I missed. I should have staged a flashback scene of Johnny returning after his meeting with Varona when he handed the note to Stefan.

It was always a little nerve wracking to be handed studio contract players. Many of them were placed under contract mainly because of their physical beauty. Whether they could act or not didn’t seem to matter. I lucked out on this production. I had already worked with Don Galloway four years prior when he had a supporting recurring role on ARREST AND TRIAL. Susan, who was only twenty-one when we filmed this episode, was awfully good, as proved by the series she starred in later — McMILLAN & WIFE and KATE & ALLIE. And twenty-four year old Steve Carlson, cast as Johnny Foster, rounded out my contract player triumvirate.

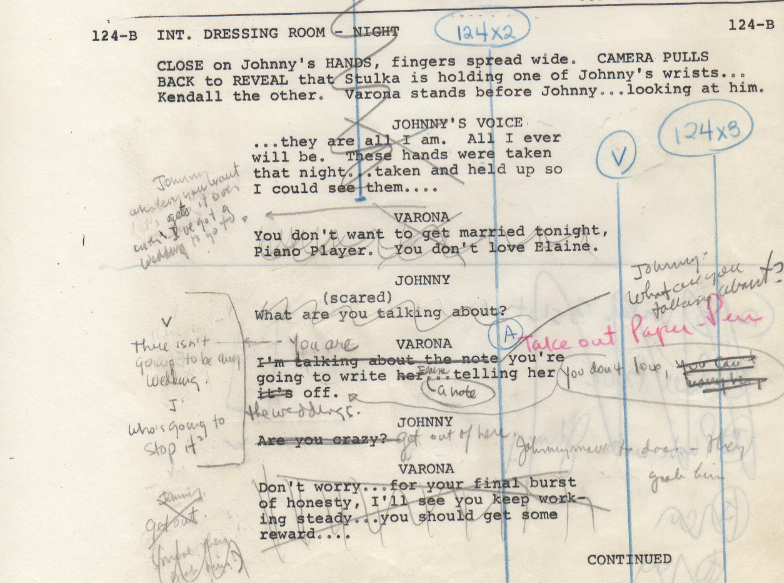

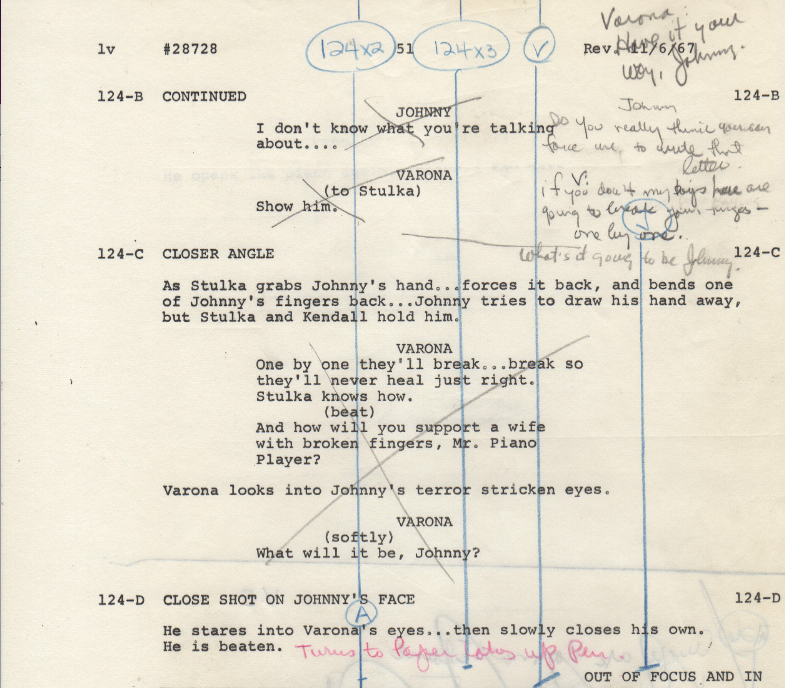

By this time I was aware that script changes should be made in advance and with full cooperation with the producer. Why I veered from that procedure with this script I do not remember. But I did. I see now that the bridge into the flashback from the previous scene to the next scene as it was written was too abrupt. I guess maybe I didn’t realize that until I was in the final stage of my preparation when blocking out my shooting script. So I ended up writing a different beginning for the scene. Producer Cy Chermak happened to be on the set when I filmed it and he made no objections to the changes I had made.

The script

The scene as filmed

I’ve said Lionel Lindon was fast. I don’t know why I remember so vividly filming the last sequence, but I do. That last shot up the stairs as Cardoff ascended was filmed and I wanted the closer angle on Elaine as she stood at the railing. I gave Curly the setup, he set one spotlight offstage shooting through the door and said he was ready.

There is some disdain today regarding filming on the studio backlots and I agree that some sequences filmed there could be shot more effectively on location. But there were many things that could be filmed just as efficiently on the backlot and it was certainly more convenient and more economical.

I never saw Lionel Lindon without a hat on his head, so I’m not sure where his nickname, Curly, came from. But on this show he was Curly, all smiles and our set was a constant ball. And boy was he a good cameraman — and fast.

The film clips of me are from a recent interview by the Archive of American Television, a division of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation.

The journey continues

Oscar Beregi, although he played a smaller role in this production of yours – as he usually did in Hollywood productions -, came from an “acting royalty” family, as you would call it. His father, Oscar Beregi Sr. was a huge stage and screen star in Hungary in the silent era. He was the leading actor of the National Theatre here in Budapest, and also starred in plays in Vienna and Berlin, and acted in lead roles of silent films. In 1933, he starred in Fritz Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. During the Fascist era, he was prosecuted because of his Jewish religion. He came to the US in the late 1940s, but only sporadically acted since then, and died in Hollywood, in 1965, two years and one month before you filmed Girl in the Night.

Thanks for bringing back fond memories of “The Dinosaur Club” (which you refer to it as he much more dignified “… Hollywood Ex-Patriot Group.” Believe it or not, I am doing a piece on our old group for my next week’s blog, and was going to ask you the spelling of Don Hamner’s last name! Great minds think alike. Best, Kit

Hi Kit: And since you asked,his name is spelled HaNMer. I just want to keep these Great Minds in alignment.

I see where Don Hanmer was in two other shows which you directed only one episode, Mannix and Dan August.

Any chance you’ll review Mannix? I would be interested as that was in the first season of the show and it was reworked after that first season, I believe.

Once again, intersting reading. Thank you.

Not totally true, if you mean I directed only one episode of Dan August. I directed 5 episodes and Don was in the first one. But Don was also in an episode of Breaking Point and one of THE FUGITIVE. As for MANNIX, I doubt that I will be discussing it. It was one of the shows about which I just don’t have a lot of memories

.

I just spent this evening watching the original “Virginian” episode and this one back-to-back, because while I have seen cases of cop show episodes getting remade on other cop shows (a later “Ironside” remade as a “McMillan And Wife” among others), this was the first time I had a chance to see how a script for a western could be reused/remade for a cop show. A very fascinating learning experience!

The rewritten beginning for the flashback scene I noticed is closer to the original version from the Virginian script, and it definitely worked for the final result here as well.

Regarding the 2nd and 7th videos – I’ve never been to Las Vegas, but “the Factory” will never get me to believe that the neighborhood and homes depicted were anything like a real residential area in that city. They could have faked a Las Vegas neighborhood much better by driving the crew to Palm Springs, but that would cost the black suits money. BTW, if you freeze the 2nd video at 0:12, you can read the movies playing at the cinema, which would date the stock film at 1963.

Ralph, did Raymond Burr’s extensive use of teleprompters add to your work in any way? I assume there was a person who loaded and operated the teleprompters. Would he wait for you to say “action” and then push a button to make it go? Would the words on the teleprompter only be Burr’s lines, or did it have the whole script?

Phil, the surprising thing I learned is that there are really two Las Vegas communities. There is the Strip, which is widely known, but there is a huge community (Las Vegas is a no state income state) that thrives whose people have nothing to do with the Strip. We filmed the house exteriors you refer to on Universal’s backlot but there are areas like that in Las Vegas. Regarding Raymond Burr and the teleprompter, there was no delay caused by their use. I never looked at what was being screened on them. I don’t know if it was the entire script or just his lines. My assumption would be his lines with just the last words of the cues.

I noticed the staircase and wallpaper in the 5th video (4:48) were also used in your other ‘Ironside’ episode, “Return of the Hero”. Both episodes are on hulu.com.

I was flipping channels last night and spotted Ben Gazzara and Julie Harris standing in the same room during a 3rd season episode of ‘Run For Your Life’.

FYI – Today, “the factory” began showing its episodes of ‘The Name of the Game’ on the COZI-TV channel at 3 – 4:30 AM. I think they’ll have it five days per week. Unfortunately, they’re not showing them in the original broadcast order. I don’t know when they’ll show your episode, “The Ordeal”. As of now, Comcast’s website lists the specific episodes up to August 13; I’ll re-check it periodically.

***********

FYI – you made the closing credits from ‘Full Circle’:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nydad0W8NCw

A soap opera website says Amzie Strickland played a busybody character. A game show called ‘Face the Facts’ replaced this soap.

Update: COZI-TV will be showing “The Ordeal” on Thursday, Sept. 19 at 3:30 – 5:00 AM (according to Comcast).

I’ve been on an ‘Ironside’ marathon lately (hulu.com has the 1st season and pilot movie for free), as I watched the episodes in no particular order. Your observation about the crews being loyal to Universal and not the series seemed to be true in the Producer’s office. I counted four different producers: James McAdams, David J. O’Connell, Cy Chermak, and Paul Mason. Later on, I discovered a posting in IMDB which has the first season episodes in production order. Assuming the list is accurate, McAdams did the first 7 eps., O’Connell and Chermak alternated for eps. 8-11, Chermak did eps. 12-16, and Mason & Chermak alternated for eps. 17-28. Do you have any insights on this?

Also, there’s a note in IMDB about the lighting hurting Raymond Burr’s eyes because he was always looking up from the wheelchair. Did the cameramen try to address this? Thanks.

I don’t think the loyalty thing was a factor in the producers. Universal was such a factory that having more than one producer for a series meant having more offices involved in script preparation. Must keep the assembly line functioning. And I never heard that about Burr and the lights.