Filmed July 1966

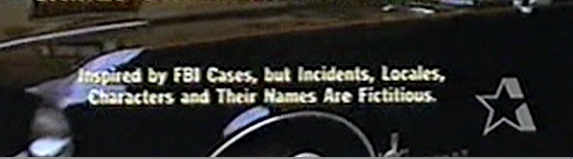

The above appeared on the final credit card of the end credits of each episode of THE FBI. I was not involved in the creation of scripts at their inception, so I can only surmise how the procedure worked. The facts of a case would be taken from the files at the Bureau and turned over to a writer to be dramatized, always bearing in mind that the work of the Bureau must be given equal prominence with the criminal’s story. Usually the method worked efficiently. In the case of THE ASSASSIN I think it worked stunningly. In the case of my next venture, THE DEATH WIND, there were some stumbling blocks. The story started in an exciting way.

The opening prolog was different than any of the previous five I had directed. In the crime that was committed not a single gun was fired. Amazingly the prolog was filmed without going near the water. The sequences on the ship at sea were filmed at the studio. The shots of the ship and the underwater mine were stock footage.

The locale of the story was the U.S. Coast Guard Base in Honolulu. Obviously (but unfortunately) we did not go to Honolulu to film it. The Coast Guard Base in southern California with the addition of art director Richard Haman’s sign, created at the studio, did a remarkably good job of portraying it.

Our third day of filming at the Coast Guard Base on Terminal Island began with Erskine and Rhodes arriving by helicopter. Normally that would be a one-take setup, but on take one the dust raised by the descending chopper raised a veritable dust storm. I thought it was cinematically exciting, but the representative from the Coast Guard assigned to our unit for the day didn’t see it that way. Take two proved to be more acceptable, proving the Coast Guard kept their heliports neatly swept.

So far not bad, and the information in the FBI files continued to add an air of legitimacy to our story.

Ralph Bellamy to me was one of the giants of the acting profession. He made his first film in 1931, his last in 1990. A dozen years before working with him in this film I had been the director of the Des Moines Playhouse in Des Moines, Iowa. The lady who ran the box office at the theatre spoke to me of having known Bellamy years before when he had his own stock company in Des Moines, which he ran very successfully for two and a half years. She spoke so highly of him. In Hollywood he made a career of playing the “other man” who loses the girl to the hero and was soon typecast in this sort of role in sophisticated comedies. I read that at one point in his career he saw a cast breakdown sheet with a role calling for a “Ralph Bellamy type.” He decided it was time to head east to Broadway where he starred in such classic dramas as TOMORROW THE WORLD (when it was filmed Fredric March played his role), STATE OF THE UNION (he was replaced onscreen by Spencer Tracy), DETECTIVE STORY (again replaced onscreen, that time by Kirk Douglas), and finally his greatest achievement portraying Franklin D. Roosevelt in SUNRISE AT CAMPOBELLO, for which he won the Tony award and the privilege of repeating his performance before the cameras when it was transferred to the screen. He was a class act, a screen legend.

As I understood it, the FBI was literally a crime laboratory, an organization created to fight crime scientifically. Richard Haman had designed a plethora of sets depicting the departments of the Bureau and they were all elaborate and more than functional. The Bureau provided us with any scientific material we needed, such as the paint cross section for the microscope insert in the following sequence.

And here we arrive at a stumbling block in the script. I know that in dramatizing the files for a weekly series it was necessary to keep Erskine, Efrem’s character, in the forefront, although by doing this it often gave the impression that he, with Rhodes’ assistance, was solving all of the cases for the Bureau. But with the Coast Guard still sending its divers down to search for evidence I found it improbable and unrealistic that Erskine and Rhodes were suddenly qualified to don wetsuits, dive down to the wreckage of the sunk vessel and discover what the professional Coast Guard divers had so far failed to find.

I did not direct the underwater scenes; they was scheduled for completion later.

The scenes in the boat were filmed on location at Terminal Island, but there was much more footage than that shown above. There were shots of the two agents boarding the boat and many shots as they traveled out to the spot where they dove into the water. That sequence from shore to diving spot was edited out for the syndicated version. The point I am making is that I filmed about twenty-five minutes of various shots of Zimbalist and Brooks in their wet suits for the sequence, shots of them boarding the boat, of the boat departing shore and many shots of the two of them in various angles on the journey out to the deeper water. The following day when we were back at the studio, production manager Howard Alston came down to the set around noon. With a bemused expression on his face he told me he had just had a call from Adrian Samish at the Goldwyn Studio. Adrian had just viewed the Terminal Island rushes and had said, “Howard, I asked you when you filmed the sequence of the boys going into the water, that you put them in identifiable wet suits, so that later when we filmed the underwater sequence, we would be able to identify them. Why can’t my wishes be carried out?” And Howard said he responded, “Well Adrian, we put Steve in a black wetsuit and Efrem in a black wetsuit with a yellow stripe on each sleeve; Steve wore a black mask and Efrem wore a yellow mask; Steve had black fins and Efrem had yellow fins; Steve was hooded and Efrem was bareheaded. I don’t know what else we could have done.” Adrian’s response, having viewed twenty-five minutes of the two guys in their scuba gear was, “Oh, I didn’t notice.”

The problem I faced with this script was that once it established the circumstances of the sinking of the ship and the marital problems of the vessel’s captain, rather than delving into and exploring those problems, it continued to heap on evermore tantalizing complications. The next one was a potential tsunami. And there were more to follow.

The original script was a series of disjointed short scenes hopscotching through the plot, some involving the FBI, some the people involved in the possible crime. That had been the case in my earlier production of THE ESCAPE. By changing the sequence of the scenes in that production, linking together some that had been separate entities, we had brought cohesion to the story and increased the intensity of the interpersonal relationships. That proved more difficult to do with THE DEATH WIND. I remember the only meaningful adjustment made was delaying a scene between the Captain and Swede and placing it immediately before a scene in Hammond’s office. This move increased the emotional impact of the ending of the office scene.

It was July, 1966, when we filmed THE DEATH WIND. It would be airing the following fall, the time of the year when Ford would be bringing out their new 1967 models. Ford wanted us to feature one of their new models in this episode, so they provided a sporty 1967 Ford for Elizabeth to drive. There was a problem however. Ford did not yet have any finished product of that model available. I don’t remember the official terminology for what they sent. It was a mockup, an old chassis with the newly designed parts of the forthcoming model attached so that in appearance it was one of their new 1967 Ford models. I was asked to photograph it to show off to its greatest advantage. Everything worked fine as Elizabeth drove into the shot, that is until she opened the door to exit the car. As the door swung wide, it almost came off of its hinges. We discovered if she very carefully limited how wide she opened the door, the car behaved.

Have you ever watched the final scene of a television show and as the final fade out appeared thought, “What was that stupid director thinking to end the story like that?” Well that stupid director was thinking exactly what you were thinking; but those were the pages on the script he was assigned and his task was to stage it as realistically as possible and hope that audiences at home wouldn’t be smart enough to know that it really was inane.

You know, directors and actors are not as stupid as the work they turn out might sometimes make them seem. I know that I have personally watched films with Barbara Stanwyck, Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert and wondered how such accomplished, intelligent performers could have been conned into signing to do the product I had just viewed. And I have learned from experience that sometimes what appears on paper to be dramatically exciting can be less attractive when it comes times to perform. In the case of directors working in episodic television, script approval was not part of the arrangement. We were booked for dates, script to be delivered hopefully three days before the contracted start of the preparation period; many times we were grateful if we received it when we arrived at the studio. What to do when you read and realized the script, or maybe just some scenes in the script, was unrealistic, overly melodramatic. No matter how deficient I found a script, my job was to totally believe in it. Some times that wasn’t easy. The sheer mountain of melodramatics in this script, plus the impending arrival of the tsunami, created a mood that was overwhelmingly depressing. Between takes to maintain a relaxed and happy set I tried to find ways to lighten the mood, for the crew and for myself. I found myself calling the tsunami the salami. But that lightheartedness came to an end when the cameras rolled. As an example once we commenced staging and filming the above finale to THE DEATH WIND, you would have thought, from the seriousness with which we approached our task, that we were staging the finale of HAMLET, but with a few less corpses.

When the photography for the show had been completed and as I prepared for my next episode, Quinn invited me to come to his office, where I received a gentle lecture on the necessity of remaining serious about my work. Obviously the sound stage “salami” had blown into his second story suite and even more ominously THE DEATH WIND did not resonate as strongly with him as my past work had. He pointed out that there weren’t enough moments like the ending of Act II.

I didn’t tell him that that moment had been possible because of the work I had done in shifting the scene between the Captain and Swede and that the problem was that the script just hadn’t offered any opportunity to create other moments like that. A few days later in a conversation with producer Charles Larson, he pointed out to me that not all of the scripts were going to be great, that I would have to accept an occasional one of lesser grade. I guess Quinn had also spoken to him. From the time of December 7, 1941, I had known of our country’s mantra, “Remember Pearl Harbor.” I now realized maybe what I should be remembering was, “Remember Paul Bryar.”

Was this the last time I would be faced with a situation like this? I’m sorry to say it was not. But was this at least the worst situation I would have to face? Again I’m sorry to say it was not. I think I wrote earlier that television was a battleground. What I was discovering was that the battleground was laced with land mines.

The journey continues

What I couldn’t figure out is if the tsunami was coming, what about all those poor people in Port Spencer? It was if, “Okay, we got the chlorine out, now everything’s fine.”

I do remember you telling me once Ralph, that there was always a gamble with episodic – that it was “the luck of the draw” when it came to scripts – I think we were pretty lucky on “The Waltons”.

Thank you for including the clunkers as the journey continues.

By the way, my wet suit has yellow stripes.

Even the great director Steven Spielberg has had bombs. So it was with this contrived episode. You just move on. Win some, lose some! I respect your honesty. It is really to your credit that you have included the bad scripts with the wonderful successes you have had in your directing journey. Anyway, any story with the great Ralph Bellamy can’t be all bad. I did not know that he was “cheated” out of roles in movies that he created on Broadway. So Sad! However, he just kept working on the next job like you. As always, Ralph, looking forward to more posts! Keep that “memory bank” open.

The tsunami was a salami and the chlorine tanks were baloneys! I thought the chlorine threat was vastly overblown. It seems to me all that stuff would dissipate quickly in the Pacific Ocean. Chlorine can be hazardous, but I never bought the imminent danger presented here.

Ralph, what happened in the Epilog? Or was it part of the 12th video?

This episode wasn’t all bad. You had one of the all-time great TV heels, Mark Richman. As for Ralph Bellamy, my first memory of him was as Mia Farrow’s no-good, rotten doctor in ‘Rosemary’s Baby’.

BTW, there is proof that someone in the QM organization had a sense of humor…at least temporarily. In an episode of ‘The Fugitive’ called “Tiger Left, Tiger Right”, they show a boarded-up building with a sign at the property’s entrance saying ‘Fir Tree Lodge’. Above that sign is a smaller sign saying: FOR SALE , John T. Conwell, R.F.D. #2

I guess I left the Epilog on the cutting room floor. As you can guess, this was not a fond remembrance. And you may be right about the sense of humor…John Conwell was the Assistant to Quinn Martin and supervised the casting of ALL of Quinn’s shows.