Filmed August 1963

After completing THE BULL ROARER at Desilu Studio in Hollywood, it was over the hills and back to Universal Studio on Lankershim Boulevard, the factory in the valley. It was my first SUSPENSE THEATRE assignment and my first adventure in color. And very definitely it was a return to studio sound stage filming. Except for a car chase sequence later in the script, A HERO FOR OUR TIME was a very talky script that owed a large debt to Alfred Hitchcock’s REAR WINDOW.

Film directors today are regarded as auteurs, as authors of their films and I heartily agree with this. Unfortunately today the commentators on television’s past apply that same current yardstick when they evaluate the work of that era. There is a lack of consideration of the conditions that prevailed at that time. With the move of television production from the live studios on the east coast to the film studios on the west coast, a new energy was injected into the floundering film industry and nowhere did it find a more welcome place to flourish than in Universal Studio in Universal City in the San Fernando Valley. When the giant MCA Corporation bought the studio, they turned it back into the giant film factory it had been in the glory days of Hollywood. But it was a factory geared to fulfill the needs of a new medium. The goal for the studio in the distant past had been to produce fifty films a year, a film a week. Now the first goal was to sell as many series as possible to the three television networks and Universal was the most successful salesman in town; and then having made the sales the studio had to produce in the season as many as thirty shows for each sale. That was an enormous amount of product to be turned out and it produced a production line mentality. Directors along with everyone else involved in production were expected to fit into that structure. Just do your job and don’t ask too many questions – they were just another small cog in the very large machine. That was not necessarily true all over town. I had not found that impersonal approach at MGM or at Desilu. But that’s what I encountered when I drove through the Universal studio gates to report for my new assignment.

I found a script waiting for me, but it was an unfinished script. Everything was scheduled to be filmed on the lot, so there were no locations to be found. I do not remember meeting with anyone from the casting department. Maybe I did because two of the actors in the show were people I would have requested, Dabbs Greer and William Bramley, but I don’t remember any casting sessions. But that was the way the studio operated. Each department was an independent entity, its allegiance was to the studio, not to the production. Under the circumstances I did not fare too badly. I was notified that Lloyd Bridges, Geraldine Brooks, John Ireland and Sandra Church had been cast in the starring roles.

By my last day of prep, I still didn’t have the complete script. The final scene was still to be written. I had lunch that day with Roy Huggins, the executive producer for the project. He was the one who was going to write the final scene. But he was neurotically nervous because he had a class to teach that afternoon (I think at UCLA) and was trying to figure out when he would have time to do the writing. What was the big problem? That scene was scheduled to be the first thing filmed the next morning. And Roy Huggins was nervous? How about me and the two actors in the scene, Lloyd Bridges and Geraldine Brooks. I vaguely remember making a frantic call to my agent to rescue me from this disaster. Somehow the schedule was changed and that final scene was filmed several days later.

The first scene that was filmed the next morning was my induction into the world of Technicolor. What I’m going to tell you won’t make a lot of sense unless you realize that the film in the color clip you will see is faded and not what the set really looked like. There was a color consultant assigned to each production to coordinate the involvement of the different departments, but obviously that coordination didn’t take place. Either that or the consultant was color blind, for the walls of the set were a subdued golden yellow, and when Geraldine Brooks made her entrance down the stairway, it looked like a floating head descending. Her dressing gown was the same color as the walls. Richard Rawlings, the director of photography, asked that the shot be stopped, and we now had the choice of repainting the set or replacing the dressing gown. The dressing gown won and was replaced after a short wait by a lavender garment that provided a carriage for Miss Brooks’ head to descend the stairway.

Three years earlier Sandra Church, who played Mace’s mistress, had been nominated for a Tony for her performance as Gypsy Rose Lee in the original Broadway production of GYPSY starring Ethel Merman. Two months later I would work with Sandra again in New York when casting director Buzz Berger and I cast her in an episode of THE NURSES. And that was a bit of casting fraught with difficulties. Sandra easily qualified to receive the top guest star salary for the show which was $1500. That was low compared to guest star salaries being offered by other productions. Quinn Martin, who may have been paying the highest figure, had a $5,000 top with no limit on the number of guests who might receive it. But on THE NURSES Herb Brodkin had a budgetary restriction that limited that salary to only one guest star per show and Edward Binns, who had a recurring role on the series as a doctor, was also booked for the episode and would be receiving that amount. I was privy to the negotiations going on between Buzz and Sandra’s agent and I was annoyed and embarrassed by what I was hearing. When I heard Buzz make an offer of $1,450 I could no longer restrain myself and I offered to personally pay the $50 difference. Buzz just laughed and told me to relax, it was all just a game. Her final salary was $1,475.

Eleven years before this, the summer of 1952, I was the assistant director at a summer stock theatre in a suburb north of Chicago. One of the early productions was JOHN LOVES MARY with guest stars Joanne Dru and John Ireland being imported from Hollywood. The day Joanne and John (who were married at that time) arrived, I was delegated to greet them. I remember they were waiting in the club’s dining room and my knees were actually shaking as I entered the room. They were the first BIG movie stars I had ever met. John didn’t seem quite as awesome in 1963.

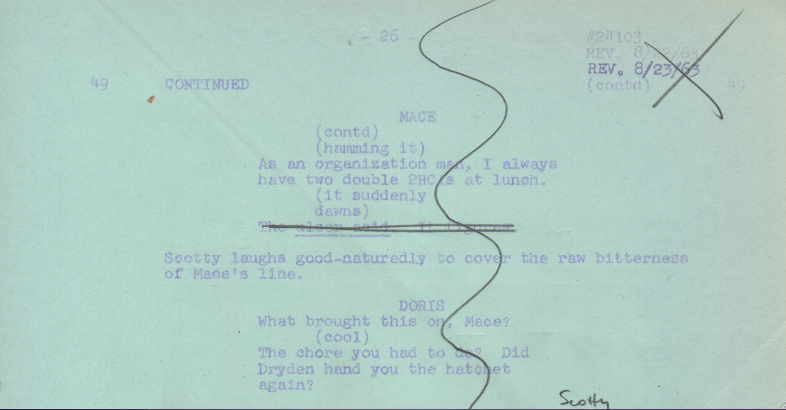

In staging that scene I made a very minor cut in Mace’s dialog.

I cut his line, “The ulcer salad. It figures.” followed by a moment of levity with Scotty laughing at what Mace said.

I felt Doris’ line that followed had more impact with the cut.

And now the clip

The following day you would have thought I had completely rewritten the scene. Roy Huggins was furious. His unhappiness lasted until the final day of filming, when we were notified that I was to film a closeup of Lloyd Bridges saying the excised line. It was the end of the day and we would have been into overtime to get the shot. I think Lloyd, without discussing it with me, realized the foolishness that was prevailing and agreed to do the shot, but he said he would need fifteen minutes to emotionally prepare himself for the scene. The assistant director, checking his watch, said, “That’s it. It’s a wrap”

Like so many of the dramas of early sixties television this one dealt with a man’s integrity. Although it started with a violent murder, its concern was not seeing the murderer brought to justice. Its focus was on a witness to the murder and his dilemma of remaining silent and seeing an innocent man convicted of the crime or speaking up and ruining his own future. The paper Mason burned at the end of the scene was a deposition he had written to send to the district attorney, giving the details that would free the falsely accused man.

I had known Dabbs Greer, who played the falsely accused janitor, since 1947 when I was a student at the Pasadena Playhouse School of the Theatre and he was an instructor and the Dean of Men. His real name was William Greer and I knew him as Bill. Bill told me he had kept the family home in Missouri and would return each year during the spring hiatus. One day he was sitting in the requisite rocking chair on the large mid-west porch when a young neighborhood boy, eight or nine years old, came by, stopped and stared intently at him. Finally the boy said, “How old are you?”

“Fifty-one,” answered Bill.

“Are you married?”

“No.”

The boy continued to stare at Bill. Finally he said, “I never saw a fifty-one year old virgin before.”

Then in 1957, I was working at CBS Television as secretary to Russell Stoneham; it was my first year on PLAYHOUSE 90. Gilmor Brown, the founder of the Pasadena Playhouse, called me one day with a request. I had by that time directed five productions in his personal PLAYBOX, a theatre adjacent to his residence. Mr. Brown (and I always called him Mr. Brown; I never could lower him or raise myself to the level of calling him ‘Gilmor’ as most people did) asked me if I would direct another production for him in the Playbox.

“What play is it, Mr. Brown?” I asked

“I don’t want to tell you until you tell me you’ll do it. Will you?”

“But what is the play, Mr. Brown?”

“I’ll tell you after you agree to do it.”

Being a Taurus I naturally outlasted him. He finally told me the play was Eugene O’Neill’s THE ICEMAN COMETH. I immediately said of course I would direct it. I would be honored to direct it. Mr. Brown then told me he had cast one actor in the production, but he had not ascertained what role he would play. The actor was Onslow Stevens. You may not recognize the name, but Onslow Stevens was a wonderful actor in both the movies and on Broadway in the thirties and the forties. I remembered him from several appearances on the main stage of the Pasadena Playhouse when I was a student. I especially remembered his RICHARD II, which he both starred in and directed. After studying the play, I decided Onslow would play Larry, the one person in Harry’s Bar who, at the play’s end, was affected by Hickey’s visit to the bar.

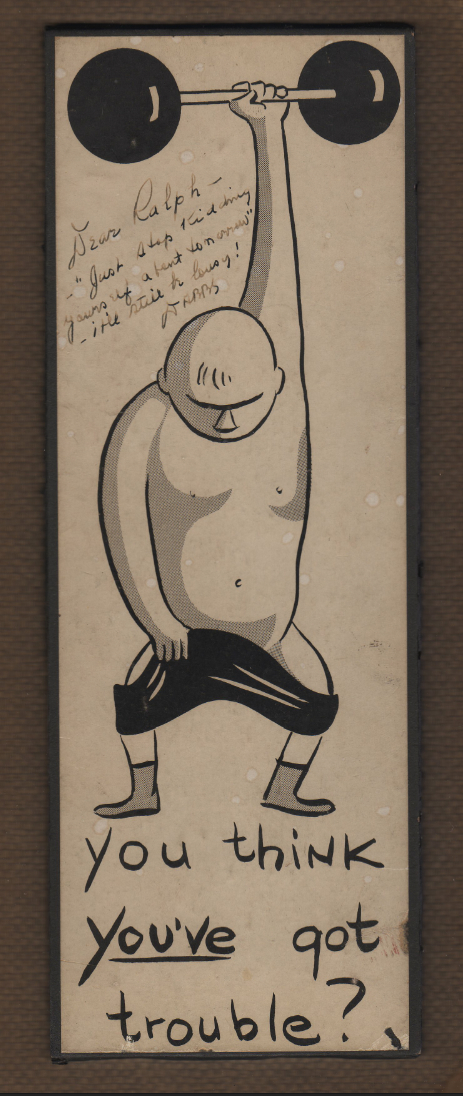

Dabbs Greer agreed to take on the role of Hickey, one of the longest, most difficult roles in American theatre. Hickey in the last act had a monologue that ran over fifty minutes. I set a rehearsal schedule of six weeks, weekday evenings and weekend afternoons. One evening midway through that schedule I was rehearsing a scene between Bill and Onslow. After a runthrough of the scene I was offering a critique to Bill, and he attacked me — ferociously and in a manner I had never seen him use. He said the role was unplayable, he was sorry he had gotten involved, but since he was involved he was going to learn the lines and that was it; there was no use discussing it further. There was no reasoning with him. I was at a loss as to what to do. Quietly Onslow interjected himself into the fracas, and Bill turned his wrath on him. It was all very frightening. Then there came a time when I was able to start talking to Bill again, and we were having a quiet, reasonable discussion, when I noticed Onslow had disappeared from the rehearsal room. It wasn’t until later that I realized that Onslow, the older theatre veteran, had deliberately stepped into the line of fire. He had seen a young director in trouble, had stepped in to deflect Bill’s anger away from me to himself and having rescued me he quietly left the room. The next evening when Bill came to rehearsal, he brought me the following.

His performance wasn’t lousy. Bill Greer gave a brilliant, mesmerizing performance. The tragedy was that Mr. Brown’s Playbox Theatre seated fifty people, all subscription, so it was a performance that went virtually unseen. It was a performance though that did gain a reputation. Three years later when I was on the DR. KILDARE staff at MGM, the trade papers announced that John Houseman was going to direct a production of THE ICEMAN COMETH for the Theatre Group based at UCLA. I had worked as a production supervisor for John when he was one of the three rotating producers who replaced the departing Martin Manulis on PLAYHOUSE 90. I bumped into him on the MGM lot where he was producing ALL FALL DOWN. I congratulated him on his upcoming production and told him I was sure he would enjoy directing it as much as I had enjoyed doing the production for Mr. Brown. John said, “Oh, you did that production!” So even if the production was not seen by many, it was talked about. And I ended up as Houseman’s co-director on his production of THE ICEMAN COMETH.

This was another first for me – my first violent car chase, a staple of crime and action shows of the period. But I didn’t shoot this one. The footage of the car chase and the car going over the cliff were lifted from some Universal feature. We matched the cars in that footage for the scenes I did film: our shots in process and the sequence at the edge of the cliff with the police officers

I find it amazing and frightening that a half a century ago the attention span of American audiences in movie theatres and at home watching television was longer than it is today; that extended scenes of characters discussing issues of morality that were the norm back then very seldom emanate from our screens today. Why?

And finally I got to the infamous sequence that had caused so much anguish at the start of production.

I honestly believe that if we had had filmed that scene the first day, it would not have been as effective.

The set for that final scene, for me, was also infamous. Universal was the busiest studio in town, mostly television productions. When a feature film would complete photography, Universal would not strike all of the sets. The better ones were left standing, to be used by the television companies. This staircase set with the black and white checkerboard floor was one of them. And it was so identifiable because of that floor. I remember the night A HERO aired, at the end of the show when the trailer for the next weeks production came on, there was that floor again.

The journey continues

I love the old style of television…Lloyd Bridges was always one of my favorites, even as a kid when he was on Sea Hunt.

The wealth of information about a fascinating, important period of TV production is historically valuable. I sense I’m in on a love story between a director and his career full of challenges. And such a well written story it is!

I really enjoyed the entire story with an excellent cast.Dabbs Greer has always been one of my favorites He played such a variety of roles. He was especially terrific in THE GREEN MILE. I think I spotted another actor that went on the greater fame. Ralph, could you please tell me if it was VICTOR FRENCH who played the killer?

Indeed it was Victor French. Somewhere in my ramblings I told of the day a dozen years later when it was during my prep period for an episode of THE WALTONS, I went down to the set and was observing a scene being filmed by the current director. I was very impressed with the performance of the guest star, Victor French. When the shot was over, Victor came over to me and greeted me effusively. At the beginning of my film directing career I had been so sure I would never forget any actor with whom I worked. I had not anticipated the number there would be. I had forgotten that we had worked together; I had forgotten about Victor’s role in A HERO FOR OUR TIMES. And as I described above, I had known Dabbs Greer from 1947 when I was a student at the Pasadena Playhouse and he was the dean of men. The collaboration with him that is most indelibly burned into me was in 1958 when I directed a production of THE ICEMAN COMETH in Gilmor Brown’s Playbox. Dabbs, or Bill as I knew him, played Hickey in a mesmerizing, brilliant performance.

When Dabbs Greer passed away in 2007 I was saddened that so little information about his long life and remarkable career was available in the general press. Thank you so much for bringing to light his background, theater work and personality in your account of him here. I wish you would write a book about all the character actors you have known, Mr. Senensky.

Was Geraldine Brooks one of those actors you have written about whose talent was never fully appreciated? I have always had a soft spot for her.

For anyone interested in seeing A HERO FOR OUR TIME in its entirety, it is currently posted on youtube at:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qEbEEBOm5CQ

Hi Moira: Yes to your question about Geraldine Brooks. My latest post as of the time i am writing this is THE MURDERING CLASS on BARNABY JONES. I write a bit more about her there. The year after A HERO FOR OUR TIME she had been cast in a FUGITIVE episode, DETOUR ON A ROAD GOING NOWHERE, and then she was cast in a movie, JOHNNY TIGER, so we released her from the commitment.She was beautiful, talented. a total professional and a great gal.

Thanks for all the info on A Hero For Our Time. I’ve seen it a few times, never thought of a Rear Window connection before but I can see it now. What lingered in my mind the longest about the episode was the relationship between the Bridges and Ireland characters, and how the latter, a beatnick type, as they used to call them (later, a hippie) engages in an ongoing moral discussion with his now wealthy “establishment” friend, and how they deal with the issues of “sticking to ideals” as opposed to “selling out”.

In the last scene between Bridges and his wife she offers her support and once again uses the phrase “selling out”, this time in praising her husband for not doing so (i.e. doing the right thing). Egads, I hadn’t heard that turn of phrase for over thirty years! Does anyone talk that way today? I rather doubt it. My generation (Boomer) did, but that was ages ago. Now young people don’t use those klnds of words. These days, you’re sort of hip or you’re not, but that’s it.

Anyway, to return to A Hero For Our Time I liked it for if nothing else raising moral issues in an adult way, with middle aged people still questioning their values; also, evolving, self-critical, willing to think, to grow. It was a reminder of the upbeat, we can solve anything New Frontier mentality of that period, and how strong it was in even some adults, let alone the very young, the soon to be teens and grownups. My generation held on to that attitude, or some of it anyway, for about a decade, then gave it up after around 1980.

John

And wasn’t it great when television (and movies) presented material for adults!

It sure is great, and I’m enjoying all those reruns,–though Suspense Theater (aka Crisis) is no longer available in my area (Boston)–MeTV makes up for this and then some. It’s so great to see reruns of those old shows. What’s more, I love black and white (go figure). There’s a beauty to it, a depth, something in the contrasts between objects, deep focus, whatever it is, as a visual-spatial person (if you’ll excuse the turn of phrase) it’s a pleasure to behold. I think it’s a major tragedy, an aesthetic tragedy if you will, that black and white film has gone the way of the horse and buggy.

Apropos of not Kraft or MCA/Universal but of studios in general, I greatly appreciate your comments on Columbia/Screen Gems. I noticed years ago the major difference between their mostly kidvid shows of “old” about dogs, circus boys and rescue teams and the serious, adult dramatic shows that Herbert Leonard & Stirling Silliphant worked on a bit later on, which were way above that level. Silliphant was a genius. At first my recent rediscovery of Route 66 and Naked City made me wary, as he was prone to overly poetic dialogue and existential musings that often went on and on, but I’ve acclimatized myself to him and his style and I now appreciate it, warts and all (so to speak). He was a hugely gifted man. I just wish he could have taken more time to write those episodes. Still, in these times of dumbed down dancing with the morons television, a half a loaf of Silliphant is, by comparison, like a full loaf of Chekhov or O’Neill. I’ll take it.

Much of the aforementioned is OT, for which I apologize. Sometimes my enthusiasm gets the best of me.

Regards, John

Ralph, since this post has references to stage dramas you directed in the 50s, maybe you can answer a question. Thanks.

To set this up, ‘Variety’ newspaper has an online archive function at varietyultimate.com. I can use it, but since I’m not a paid subscriber, all I can retrieve are fragments of columns.

I’ve played around with the archive and noticed that when ‘Variety’ wrote about a play being performed, they sometimes used the adjective “legit” to describe the production. Or a play will be called a “legiter”. For instance, the June 10, 1958 issue has an article on the Pasadena Playhouse production of ‘Bus Stop’ (starring Mala Powers). Its title is ‘Legit Review’. What is implied when a production is described as legit (or legitimate)?

FYI – I found this ‘Variety’ snippet from Oct. 6, 1958, which I think is for “The Innocents”:

for adults. Competently directed by Ralph Senensky, production supervisor for “Playhouse 90,” the Santa Monica Theatre Guild’s presentation frequently chills – but not to the marrow – and the script is as puzzling now as it was when it opened in New York in 1950. A girl, 8, (Sandy Descher) and her brother, 12, (John

Phil: To answer your question about legitimate theatre, I googled and went to the Wikipedia definition:

The term “legitimate theater” dates back to the Licensing Act of 1737, which restricted “serious” theatre performances to the two patent theatres licensed to perform “spoken drama” after the English Restoration in 1662. Other theatres were permitted to show comedy, pantomime or melodrama, but were ranked as “illegitimate theatre”.

Somehow the term survived for centuries and I think in our time it referred to all theatre prouctions.

FYI – the Antenna TV channel will show this episode on Sun., 7/14 at 5 PM (Eastern). Currently, they are showing ‘Suspense Theatre’ on Saturdays and Sundays at 5 PM.

Ralph, it’s been a LONG time since I dropped a note here, but thanks so much again for all your contributions to American TV. I lost my dad recently (almost got to 90), but I’m happy you’re still with us!

As for Dabbs Greer, he was amazing in this crude clip from your production of ‘Winesburg, Ohio’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMNp43kbmYI

Phil: How great to hear from you. I really missed your contacts with this website. Accept my condolences for the loss of your father. I know what a loss that was. I lost my father when he was 55. And thank you for the WINESBURG OHIO film. clip Years ago when I started this website I purchased a DVD of WINESBURG OHIO from whoever owned it at the time, hoping to do a post of it on this website.. The screen of the DVD had the name of the company representing the film plastered across every frame of the film so that I was unable to tell the fabulous story behind the taping of the show. And it was a fantastic story. Jean Peters was coming out of retirement to play the mother. Jean was divorced from Howard Hughes and the way we dealt with that problem was unusual. It is a tragedy Jean’s terrific performance has not had the exposure this website would have provided. Plus the other great performances!