Filmed November 1963

Samuel Goldwyn once said, “Pictures are for entertainment, messages should be delivered by Western Union.” It’s a funny line, but I’m afraid I don’t agree with it. I don’t like propaganda. I don’t like preaching. But I do like to work with material that has something to say. Jerome Ross, in writing this piece, had something to say. And in saying it he cleverly avoided the built-in trap in the original concept for this series — the problem of the detective who arrested and the defense attorney who defended being on opposite sides.

The problem of trying to avoid having one of the two stars of the series ending up loser of the week was solved by Jerome Ross by having defense attorney Egan’s focus be on the medieval drug laws of the country rather than the defense of a recalcitrant Hoagy Blair. And I ignored executive producer Frank Rosenberg’s objection six month’s earlier to my staging this meeting in the attorney conference room by deliberately including other people in the over the shoulder shot of Mickey. I don’t remember any objections this time.

Milton Shifman, the film editor for this production, used a splicing instrument I had not seen before. The prevalent method used at the time was the hot splicer. Two strips of film to be spliced together were laid in an electrified splicer, the film ends were scraped with a razor, glue was applied, and the ‘lid’ of the splicer was clamped down and heat was turned on. Milt had a special splicer (I think it was foreign made) and he TAPED the two strips of film together. Since tape for splicing was not being made at that time, Milt’s splicer punched holes in the tape to match the film’s sprocket holes. In not too many years special tape with sprocket holes was produced, and tape replaced the hot splicer in Hollywood’s editing rooms.

Milt was an excellent editor, but he did something that I found irksome. When I shot the coverage angles of Mickey, I always made sure the ‘look’ (does he look camera right or camera left?) matched the looks of the other people in the scene. If they looked left when looking at Mickey, Mickey should look right. And vice versa. I also varied the size of Mickey’s closeup to match those of the other people. As the story progressed, Mickey’s closeups became larger and more dynamic. Well Milt especially liked a close-up I shot for one of the later, more dramatic testimonies, and he used it almost exclusively for the entire courtroom sequence, and most of the time the direction of the look was incorrect.

The big close-up was used correctly when Harry Needles was on the stand testifying. Hoagy was looking at Egan.

ARREST AND TRIAL was my first lawyer film; it was my indoctrination into courtroom staging. There is something fascinating and dynamic about such sequences. But they are difficult because those scenes are made up of questions and answers and speeches — total dialogue. And the only person moving about is the attorney doing the questioning. I don’t remember from whom I learned it, but one of the tricks attorneys use is to stand by the jury, so that the witness on the stand is looking at him AND THEM as he testifies.

Roland Winters, who played Linda’s father, was the third movie Charlie Chan. He was cast in 1947 when Sidney Toler, Charlie Chan #2, passed away. Roland was forty-three years old at the time, just five months older than Keye Luke who played Charlie Chan’s son.

The judge in this episode (and several other episodes of ARREST AND TRIAL) was Bill Quinn. a close personal friend. Bill had been acting since beginning his career at the age of six as a child actor on Broadway. You may recognize him as Mary Tyler Moore’s father on her long-running television series or as the Blind Man on ARCHIE BUNKER’S PLACE. Offscreen he was Bob Newhart’s father-in-law.

Mickey Rooney was a marvel to watch. And he had a ball during the courtroom sequences. Why? He had a captive audience. During the time a new setup was being lit, Mickey would entertain the fifty extras who were the audience in the court. Stories. Jokes. When the set was ready and the assistant director called places, Mickey would finish his routine, and as the audience gleefully responded, he would turn around, sit down at the defense table, and by the time I called “Action”, he was totally in character, tears streaming down his cheek if the scene called for it. During one of these takes I was standing by Judge Bill Quinn, and I heard Bill mutter, “That son-of-a-bitch, how does he do it?”

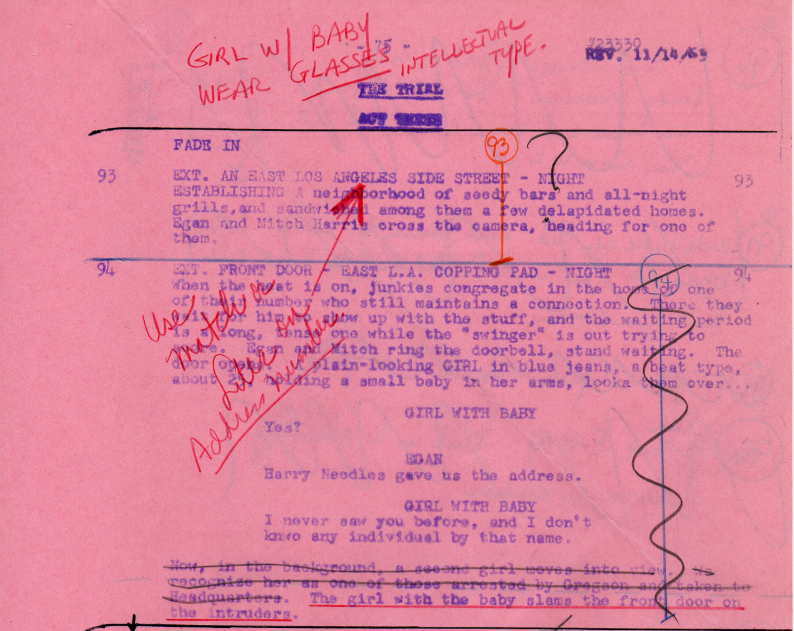

The exterior for the sequence where Egan goes to the address Harry has given him was scheduled to be filmed on the backlot. I cut the establishing shot of the house with the two men arriving, wanting something crisper and stronger that would take less time to film. I decided they would use a match to light the address number.

It proved to be more expedient than I had anticipated. John Russell, a superb cameraman, used ONLY the flame of the substituted cigarette lighter to light it.

There was a long standing belief that acting in films was easy because the actor only had to do a little bit at a time, and these bits would be cut together in the editing room to create the performance. Not always true. When the scene was well written, I liked to do long extended takes. I also made it a standing rule right from the beginning that in courtroom scenes, I filmed with two cameras. That helped to speed things up when doing the reaction shots that were always so numerous in courtroom scenes. But it also meant that if the person in the witness stand had a long emotional scene, filming the wider shot and the closeup at the same time took away the pressure of the actor having to do the scene twice, and it also insured that when the performance really took off and became alive, I was getting it in both cameras. That was very evident when Mary Murphy as Linda Blair took the stand to testify.

During most of Linda’s testimony, editor Milton Shifman used the closeup of Hoagy that had been filmed for the scene. Most of the time, but not all of the time. And what before had been merely irksome, now became downright ridiculous

[S3VIDEO file=’arrestandtrial/funnymantrial/two_linda_a.mov’]

Seated behind Hoagy in the courtroom was his wife at the same time that she was on the stand testifying. Did Shifman do it only once? No.

Did he do it only twice?

That’s all. Fortunately he had obviously used up all of the film of that revered closeup of Mickey Rooney.

In the summations to the jury, Jerome Ross delivered one of those messages sneered at by Samuel Goldwyn.

Those words were written two years shy of a half a century ago. A decade later the US government under Richard Nixon enacted the War Against Drugs laws. Forty years later those laws are still in existence, but are currently (again) under attack. A report has recently been issued by an international panel of distinguished leaders declaring that the war has been a failure, and for the very reasons so eloquently stated in this script by Jerome Ross so many years ago.

Jerome Ross also accomplished something else. His script was uncompromising in reaching a powerful and painful verdict for Hoagy Blair. But detective Anderson and attorney Egan both managed to come out heroes in their respective duties.

Stephen Bowie wrote on his fine Classic TV History Blog: “The episode that most Arrest and Trial staffers remember, and the one that may rank as the best of them all, is “Funny Man With a Monkey.” Nominally the story of Hoagy Blair, a heroin-addicted nightclub comedian who plans to challenge existing narcotics laws in court after his arrest on a drug-related homicide charge, “Funny Man” is actually a semi-documentary tour of the nightmarish world of chemical dependency.”

The journey continues

Ralph, so many surprises – and the ending – wow! You must surely be proud.

The third video is stopping at 1:21.

I like the ‘counter-intuitive’ casting of Chuck Connors as the defense lawyer, instead of the cop. If Chuck showed up at your front door and flashed a badge, you’d immediately confess to stuff you never did. It looks like he had fun doing the courtroom summation.

Thank you, Phil. The third video is now fixed. You can continue enjoying Chuck’s enjoying being an attorney.

Ralph, I cannot tell you how much I’ve enjoyed reading your blog. Your recollections and commentary are so vivid and insightful … highly enjoyable. And I appreciate how you utilize video clips to emphasize points of interest. I first came across your name while watching my “Naked City” collection. That led me to find your TV Archive interview and then this blog. Suffice it to say I am now building a collection of the great TV shows you worked on during this period.

Your blog helped me discover “Arrest and Trial” and I’ve been working my way the entire series. What a great show! Please offer your thoughts of working with Chuck Connors, Ben Gazzara and John Larch. I find them all to be wonderful in these roles. Having known Chuck Connors primarily from “The Rifleman”, it was a revelation to see him portray John Egan on this show. He exudes much power and confidence in this role. I was never a fan of Ben Gazzarra; I found him a bit remote and stiff. (I also envied him as the lucky guy married to beautiful Janice Rule!) But in watching these shows, I’ve developed much greater appreciation and respect for him as an actor. I could easily see him playing either the policeman or the defense attorney. Veteran character actor John Larch was the biggest surprise for me; he brought surprising depth into many of his characterizations. I particularly recall his amazing performance as the police officer coming apart at the seams in the Naked City episode “Today the Man Who Kills Ants Is Coming”.

Interestingly you have written my response to your asking me to comment on working on the three actors. Chuck was an athlete turned actor who in ARREST AND TRIAL was cast against type and gave a fine performance. Ben was an acclaimed Broadway actor whose film performances improved the longer he worked before the camera. And John Larch was another of that huge group of character actors who never achieved stardom, but boy, did he know his craft. All three were total professionals and I found all of them very easy and pleasant to work with.