FILMED January 1966

THE MAN WHO WENT MAD BY MISTAKE was the second THE FBI that I directed. It was the only one of the eleven that I directed in the first two seasons that I have not (so far) included here on my website. RETURN TO TOMORROW, an episode of STAR TREK, was another production I resisted writing about. A year and a half ago on September 7, 2012, after many Comments left on my website decried my omission, I finally did a post for it. In writing about that show I tried to examine why my own feelings about the production had been negative for an episode that had had a profound effect on so many fans – I might add on so many who were YOUNG people.

My favorites of the QM Productions that I directed were THE FUGITIVE and TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH. THE FUGITIVE ran for four seasons; TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH for three. THE FBI ran for nine seasons. It was the most successful series that Quinn Martin ever produced. Why the discrepancy between my lesser assessment for my films on that series and their enormous success?

THE MAN… was the first episode of THE FBI that I directed that was photographed by William Spencer. This was several months after our illuminating for me association on TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH, the series for which Billy won an Emmy for his black and white photography. Because Billy was away filming a pilot for Quinn Martin, the cameraman on SPECIAL DELIVERY, my first THE FBI, had been Harold Wellman. This was also the first film in color Billy and I did together. Billy hated color film. He told me that when he watched television at home, when it was a color show, he would adjust his set and watch it in black and white. I think the remarkable thing about his work in color film is that he lit it as if he was filming in black and white.

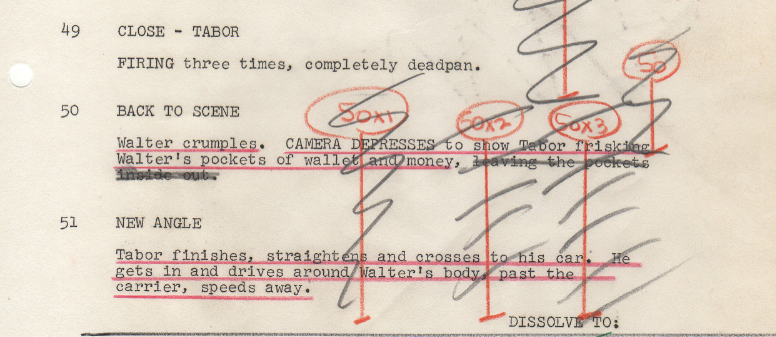

By January 1966 I had been directing film for four years and three months. I was aware that I did not have the freedom to make script changes in dialogue on the set, but there were no rules that I had to adhere to the author’s staging. I made it a practice that as I prepared a film, I retained the few instructions for staging that I found useful; all others were scratched out. Here is the script for the ending of the killing of Walter scene:

You will note that after Tabor took money out of Walter’s pocket, I eliminated “leaving the pockets inside out.” In the preceding scene Greene said, “…He was a hit man in the beginning – a contract killer. Always the same M.O. He made the job look like a hold-up. Took the wallet – pulled the pockets inside out….” Since the inside-out-pocket was not used as a clue by the FBI later in the film, I wanted Tabor to push the pocket back in, deliberately and decisively avoiding any M.O. connection to his past.

My experience directing “crime” shows was still very limited; there had only been NAKED CITY and ARREST AND TRIAL. But THE FBI was different. For openers the scope was wider – nationwide. And the Bureau was very involved. Two FBI agents were assigned to the production company in Hollywood to provide technical guidance. And the Bureau was very protective of its image. The appearance of actors cast as FBI agents had to adhere to a strict visual formula. I used to joke that they all looked like MCA talent agents, except they weren’t restricted to wearing black suits with slim black neckties. If the Bureau found fault with any actor cast as an agent, that actor would never return to the series. In the crime shows I had directed (and would direct in the future) I always thought the criminals’ scenes were more interesting than those involving the law. On THE FBI there was even more time devoted to the activities of the crime chasers. Many of those scenes were providing exposition information, many were agents questioning people, an incredible number of them were telephone conversations, not the most exciting kinds of scene to stage.

Robert Chapman, the actor cast as special agent Cambria, reporting from the auto transport lot, was a perfect example of the type to play an FBI agent. A decade before he had been in my cast of BELL, BOOK AND CANDLE, a stage production in Gilmor Brown’s Playbox in Pasadena.

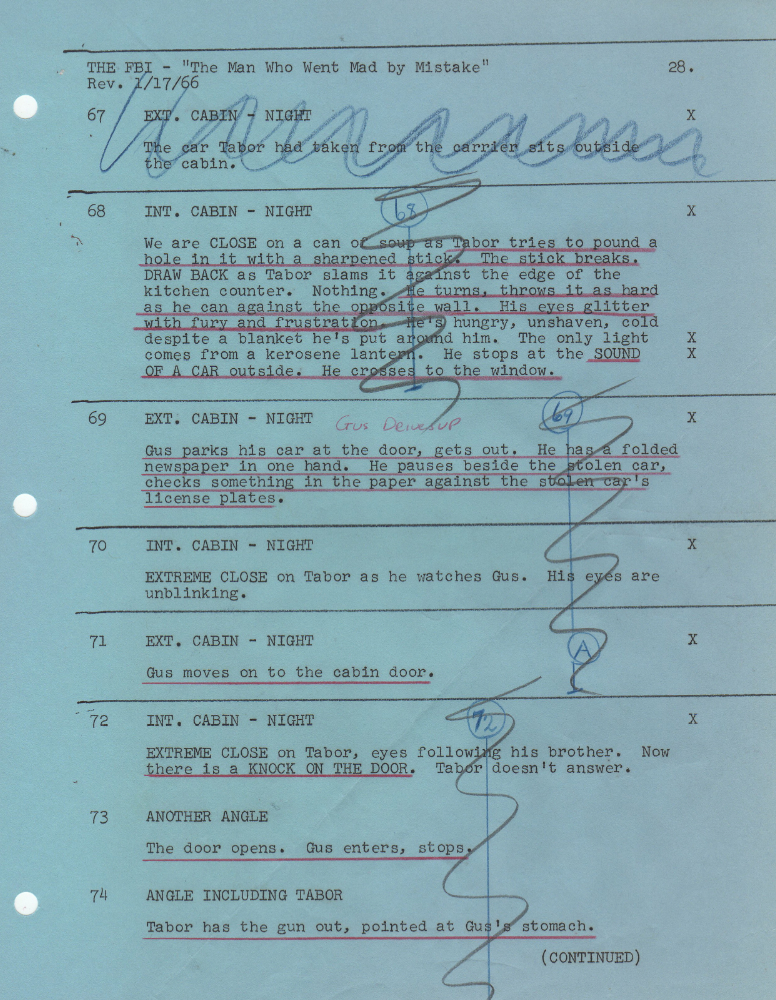

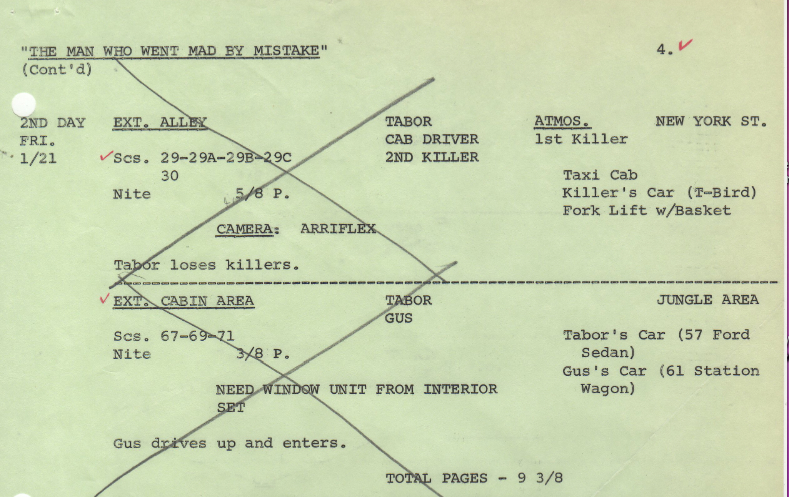

During prep week a change was made in the script to facilitate production. The second day of filming, a Friday, we were scheduled to do an important Cabin scene between the brothers, the Book Store scene between the two of them plus two other scenes on Stage 22. We were then to move to the back lot for four night sequences in three different locations. One of those locations was the exterior of the cabin.

When the schedule was created, the production manager included instructions for the Exterior Cabin Area: NEED WINDOW UNIT FROM INTERIOR SET

Total pages for the day: 9 3/8. With the extensive night work on the backlot, that was heavy. To further complicate the situation, George Tyne, playing Gus, had been booked for only one day. Art director Richard Haman and I put our heads together and decided that if he added more greenery to the set on Stage 22, I could shoot the business of Gus arriving and checking the license plate from inside the cabin across Tabor’s body through the window, removing the necessity to make the move to the cabin area on the backlot. By also eliminating the establishing shot of the cabin, we had saved a considerable amount of time, ensured that the scenes with George Tyne would be completed in the one day and made Friday’s schedule possible.

This was the only time I worked with George Tyne (Gus), which I regret, because he was an exceptional actor. He had a very interesting career. He appeared in movies, television and on the Broadway stage. He was blacklisted in film between the years 1951 and 1964. He also had a very successful career directing television. I have a special respect for competent and talented jack-of-all trades like George.

THE FBI was the third Quinn Martin series that I directed; THE MAN WHO WENT MAD BY MISTAKE was the tenth show, and as always the casting was first- rate. Recently there has been much belated but deserved acclaim for casting director Marion Dougherty. I would like to state here that I thought the casting directors in the Quinn Martin organization were her equals. Headed by John Conwell, an excellent ex-actor, almost all of them were also excellent ex-actors: Dodie McLean, Tom Palmer, Bert Remsen and Jim Merrick. There’s an old saying: It takes one to know one. I think that thought applies here.

THE MAN … was the first time I directed Simon Scott (John Goddard), but not the first time we worked together. Eleven years earlier I did the lighting for the Players Ring production of SATURDAY’S CHILDREN. Danny (his real name was Danny Simon) was the star. I think I used Danny as a guest artist more than any other actor. Through the years we worked together seven more times.

It was also the first time I worked with Michael Conrad (Paul, the therapist). Later I directed him in THE TYRANT on PLANET OF THE APES. Michael is best known for his recurring role as desk sergeant Phil Esterhaus on HILL STREET BLUES, for which he was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Emmy Award four years in a row. He won twice.

Harold Gould (Superintendent Arnold Bruzzi) was another exceptional actor. Having earned a PH.D. in theatre, he taught speech and drama at Cornell University until he decided to become a full-time professional actor. We had worked together a year before on THE THREAT, the episode of TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH when John Larkin, one of the series’ regulars, died mid-production. There was one sequence with Larkin that was only half-finished. It was rewritten for Harold’s role, so that the words and business previously assigned to Larkin’s General Crowe were performed by Gould’s Colonel Reed. The demotion in rank did not affect the scene.

Because of Erskine’s going undercover, the FBI was more involved in this case, as it had been when he went undercover in SPECIAL DELIVERY, the first episode of THE FBI that I directed. As a result Erskine became a very integral character in the criminal’s part of the plot. His going undercover occurred only one more time in the other fourteen episodes I directed.

The red brick building of the Valley View Neuropsychiatric Institute was a standing set on the Warner Bros. backlot, but it was not a complete building. Like most of the structures on studio backlots, it was a façade – just the outer facing of the building. This was the first time I photographed it, but definitely not the last. The following year without the menacing fencing it became a college structure in the episode of THE FBI, THE ASSASSIN. A decade later I would use it again as a college building, but in Virginia in the 1930s. That was on THE WALTONS.

I think my problem with this episode had to do with the ending. To start with, the fight between Erskine and Tabor was overdone. The vaulting over railings and leaping up onto the gate looked like what it was – two stuntmen doubles. The hospital staff materializing on the grounds in the middle of the night, Rhodes’ last minute arrival – too much, too soon. Too melodramatic! And Tabor’s last minute breakdown into insanity – I now question that. There was no preparation for it! Three years earlier in IN THE CLOSING OF A TRUNK on ROUTE 66 Ruth Roman as Alma gave a searing portrayal of a woman sinking into madness. But there were subtle hints throughout the drama of her character’s emotional disturbance. Her final descent was totally believable. J.D. Cannon’s Tabor was a shrewd, intricately etched performance of a man always in control. In the cabin scene with Gus when he realizes Gus will not lie to protect him, when he breaks down emotionally and plays the dependent younger brother pleading with his older brother to “take him home before he beats up anybody else,” he seemed on the brink of madness. But when Gus left to prepare the car, Tabor wiped away a tear as he looked at a note he had written – his plan that the next move was into an asylum. So the only remaining question: was he insane all along?

Very interesting. Brings back lots of memories.

I agree the ending was too much, too soon. I noticed in the script it was written Tabor fired three times. It looked like he only fired twice.

Also after Walter was shot Gus tells Tabor that Walter lived. In the conclusion ,Erskine is told that Bruzzi will live. Was this done to tone down the violence?

Roy Engel had a small role. I remember him from various episodes of Gunsmoke, including the two-part “Snow Train,” one of the most popular Gunsmoke episodes.

Finally, being from Chicago I was wondering if the Chicago shots were done by a second unit? I noticed the marquee on the Chicago Theatre was for the film, “The Sand Pipers,” with Richard Burton and Elizabeth taylor.

Starting at the end, the establishing Chicago shot of the Loop was a stock shot.

As for everybody living, that as the way the script came to me. It could have been a standard procedure. The networks wanted the violence, but they wanted the brakes applied as to how it was presented.

This was one of those episodes that did not let you down in any way. The action that you followed the FBI for and the twists and turns that you expected from Quinn Martin Productions. JD Cannon was almost a staple of QM shows back then and always very dramatic and intense in his delivery, this was no exception. Nicely put together overall. I would have liked to have seen a bit more close ups in the confrontational ending but that is just my preference and minor at that.

I am convinced we missed a lot of aesthetic details in those days of CRT televisions, but a bonus to pick all that up today with more current equipment–bringing out the real details that producers aimed for. This makes another grand addition to the classic annals of the Golden Age of Television