FILMED July 1977

I missed John-Boy. I knew John-Boy Walton better than I knew Richard Earl Thomas. I had been involved with John-Boy from when he was a seventeen year-old confused teenager struggling with his conscience over what to do because of seeing Yancy Tucker stealing chickens. I was with him when he went with Grandpa Walton to the mountain home of Martha Corinne and was almost killed because of her battle against the government when she refused to leave her property. And then that arduous week when against his mother’s wishes he entered a dance marathon and realized for the first time the desperation in people that was caused by the depression. I watched later when, like the hero in Ibsen’s ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE, he faced the wrath of his community because of his desire to print something in his newspaper for their edification. And finally on our last association I saw him deal maturely with the situation with Martha Corinne.

I also missed having the character of John-Boy in the story. As I related before, Earl Hamner in his fine book, GOOD NIGHT JOHN-BOY, wrote that the role of the father had been offered to Henry Fonda, who turned it down saying, “It’s the boy’s story.” And now that boy had grown up, was gone and the basic structure of the stories was different.

I knew the collective Walton family better than any other group of people from the many shows I directed. A director in a way was the co-creator with the author, the co-parent of the people in the dramas and comedies he helmed. And I directed more THE WALTONS than any other show except for THE FBI, and that was really an anthology series.

Something I learned early in my training was the importance of finding the comedy when doing a drama. It did more than provide relief from the heavier goings-on; it provided a contrast, so that serious events following something comedic would be even more dramatic. Fortunately Rod and Claire Peterson, who wrote this script, believed as I did.

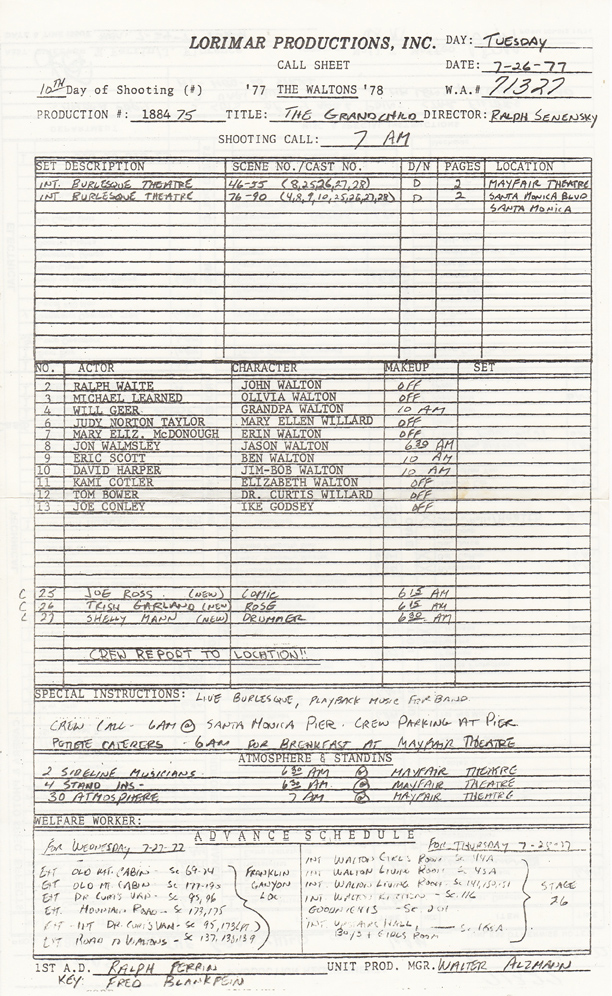

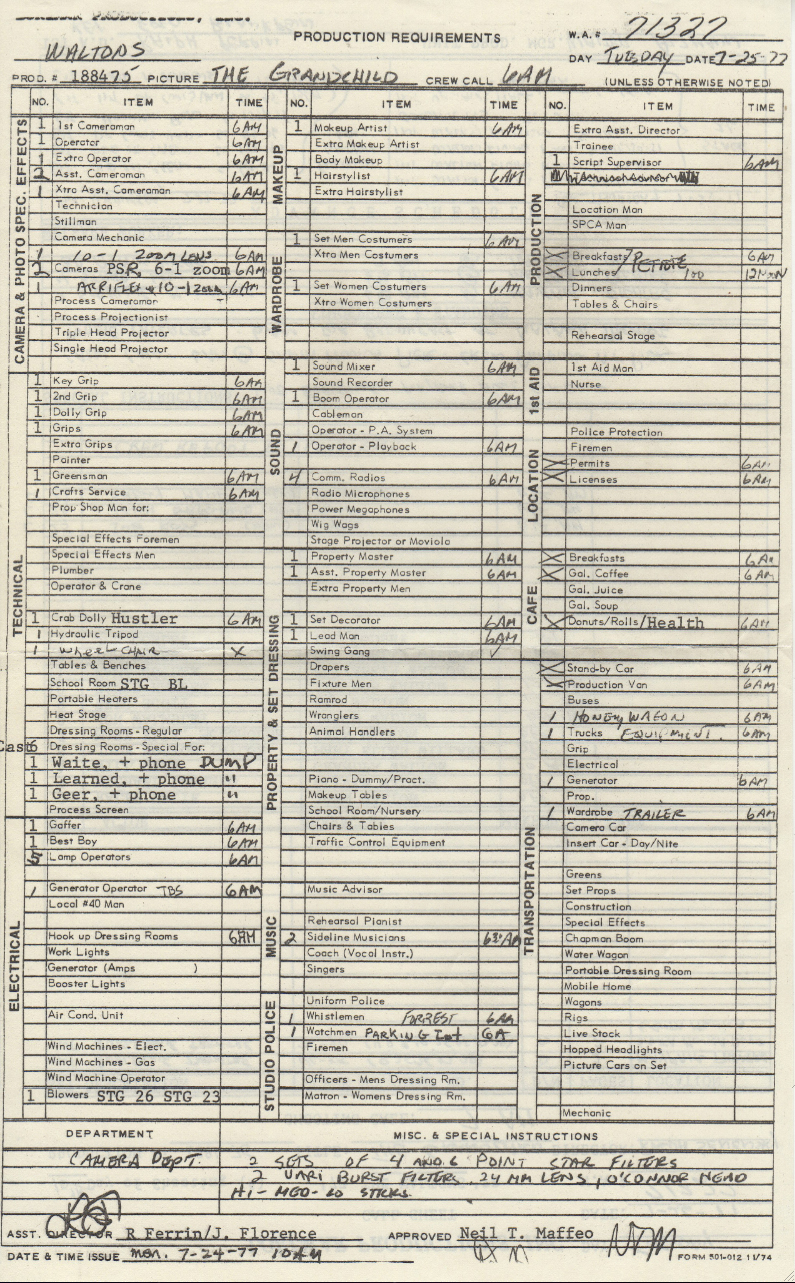

Earlier I have shown you pages of the shooting schedule that were issued during the preparation period. Once filming began a call sheet for the following day’s work was prepared each day by the production manager and distributed to the cast and all of the production departments. The sheet listed the on-camera personnel and their time to report to makeup.

On the other side of the sheet was listed in detail the production requirements. For our day at the Mayfair Theatre to film the burlesque house sequences note that 2 cameras were ordered with specific lenses and special filters; and all of the crew were given their report time.

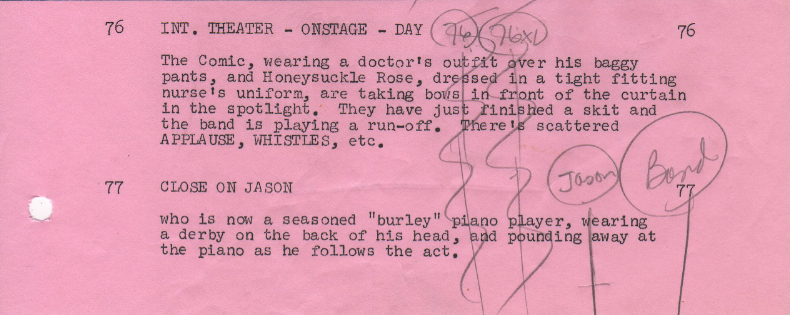

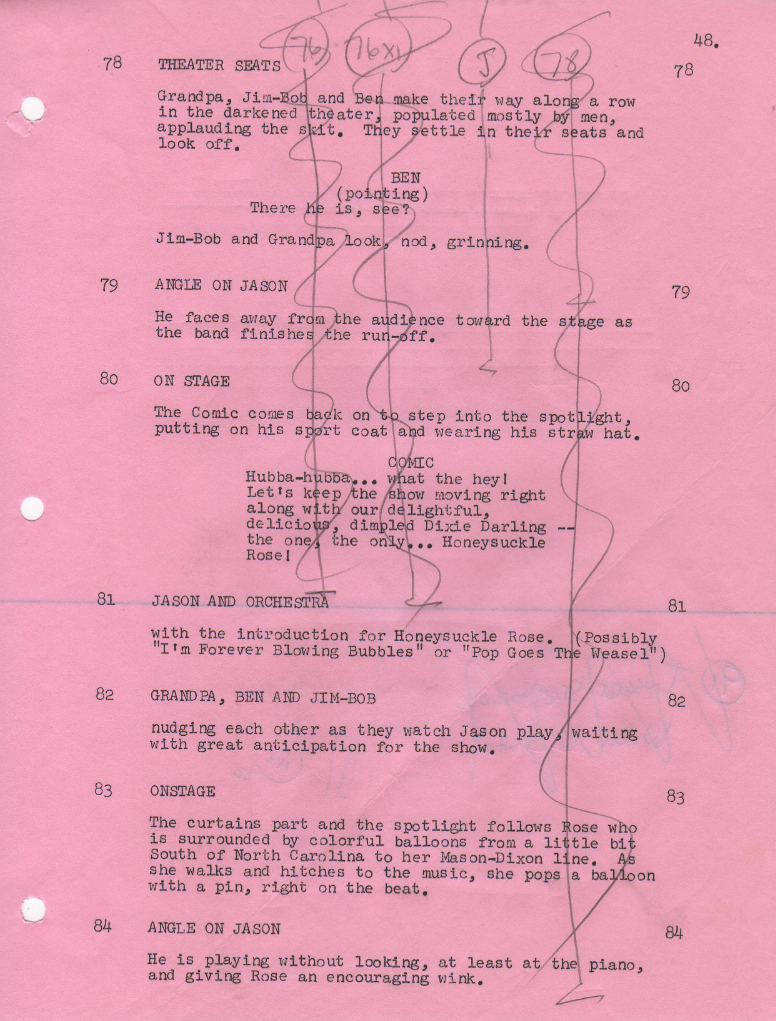

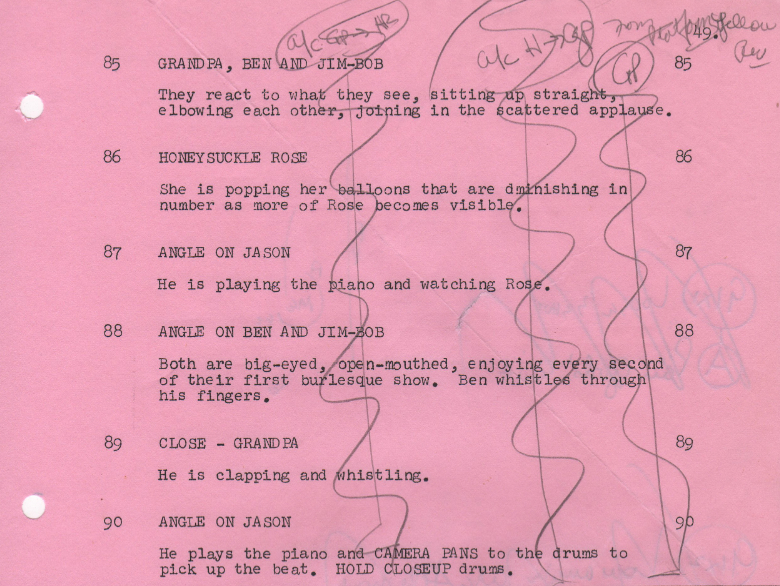

There were four pages scheduled for our tenth day of filming the burlesque theatre, two pages for each musical number. Because I had no contact with Trish Garland from the time I cast her and arranged to have her create her own choreography until the morning she showed up on crutches at the Mayfair Theatre in Santa Monica, I had not done my usual preplanning. I did that at the theatre while the equipment was being unloaded. But a lot of what I preplanned and shot did not make it into the final cut, and as we rehearsed and filmed, changes were even made in what I preplanned.

The sequence that survived came to just one minute, but that one-minute required ten camera setups. The film that was eliminated (Grandpa and the boys coming down the aisle, the comic and Trish onstage finishing a sketch) was additionally half that. The earlier burlesque theatre sequence in Part I was a more complicated dance and required about seventeen setups for its two minutes. What I’m trying to say is that we had a full day’s work to complete and with an injured dancer. When we returned after our catered lunch the crew, having a shorter break than the actors, had the first afternoon shot ready to film about five minutes before the actors’ lunch break was over. Trish Garland was on the stage ready to go. Jon Walmsley, who was to be at the piano in that first shot, was seated in the theatre, and he refused to start until his meal break was officially ended. I was surprised and stunned at his behavior. I remembered that on DAN AUGUST Burt Reynolds would wave his right to added pay if after a strenuous day filming he reported the following day before his twelve-hour turnaround. This was less than five minutes and Jon was merely sitting there, enjoying the star power he was displaying. Four working days later I was scheduled to start prepping another episode. I had already received the script and it was a story in which Jon’s character of Jason was the leading protagonist. When we returned to the studio the following day I arranged with producer Andy White to have another script assigned to me.

And there was a fourth departure from Walton’s Mountain since I had last been there. Reverend Matt Fordwick (John Ritter) had resigned as the minister of the local church and had left the mountain and CBS to go to ABC, where he took up residence with two beautiful women for an eight season run in THREE’S COMPANY. His replacement was young Peter Fox, delivering his second sermon in this episode as Reverend Hank Buchanan.

I had spent my internship and residency at Blair Hospital on DR. KILDARE without overseeing the birth of a baby. Four years earlier on THE WALTONS I almost had the chance when Olivia was pregnant, but she had a miscarriage. Finally my chance had arrived., but unfortunately not under the best of conditions.

On July 20, 1977, Nora Marlowe as Mrs. Brimmer filmed the kitchen scene with Erin, Jim-Bob and Elizabeth. On July 22 she filmed the party scene where she read the tea leaves. THE GRANDCHILD aired the evening of November 3. On the last day of the year, December 31, 1977, Nora Marlowe died.

Ralph is not as common a name as Bob or Dick or John; so I very, very seldom had to contend with having other Ralphs on the set. But that was not the case this time. Beside me there was Ralph Waite, our assistant director, Ralph Ferrin; and to add a little more confusion to the mix, the actor playing Mary Ellen’s husband, Tom Bower — his middle name was Ralph.

This was the least typical Waltons script handed to me so far; another strange one was still in my future. That is not a complaint, just a statement of fact. Walton stories didn’t usually veer from human drama into melodrama.

The journey continues

Ralph – thank you for the publishing the Call Sheet – that was Joe Florence’s scribble. It was not long after that I got the job of filling out the Daily Call Sheet – and everyone was duly impressed with my neat printing – actually anything would have been better than Joe’s. He was relieved I was eager to get the job. We’d fill it out during the day and send it off to Neil in the evening for approval. When I tell young AD’s we wrote those Call Sheets and also the Production Reports by hand they can’t believe it – plus we had no computer software, all the breakdowns were done by reading the scripts – an plotting the boards by using strips of cardboard. I know you know that well!

Notice there is no #1 or #5 on the Cast Call Sheet — out of respect for Richard (#1) and Ellen (#5) the Cast on the Call Sheet was not renumbered. It was a nice gesture, and reminder that they were missed. It was a feeling, a tone that was set by Earl.

I noticed that Ralph said, “Damn, I hate to wait.” that surprised me – I think he slipped it in.

Did you know about that? Was it approved, and in the script? I’ve no recollection, and had to rewind the clip several times and listen carefully. Certainly it was a natural thing for John Walton to say “Damn” at the moment his daughter was in pain.

Early on in the series there was an infamous note from CBS to Earl and everyone on set asking that it be made certain that a piece of dialogue Richard had be clearly understood NOT to be the word damn. How times have changed.