FILMED November 1973

When I returned to THE WALTONS in November, the script I was assigned to direct felt like a gift. It was going to give me the opportunity to make an audience cry. My main goal when directing has always been to involve an audience, to affect them emotionally, to make them laugh or bring them to tears. Now I’m sure you agree with the making them laugh part, but you may think that wanting to make them cry is a strange thing to want to do. But really there is very little distance between laughter and tears. Haven’t you ever laughed until tears streamed down your cheeks? Haven’t you ever been involved in an emotional situation that at the time brought a smile along with the tears. I have. Recently I was at the bedside of a very close friend who was dying. There was a serenity in her fearlessness as she approached her end that gave me a warm glow to accompany the tears. During the early sixties when television drama was changing from the live STUDIO ONE’s and PLAYHOUSE 90‘s to film series like NAKED CITY, ROUTE 66 and DR. KILDARE, there was a prevalence of scripts that gave me opportunities to produce both effects. But those series soon disappeared. Their replacements tended to be more action oriented, lots of crime and police dramas more concerned with how the action occurred than why. And I did my full share of them. They broadened my capabilities, but I did miss that missing why which had departed. It was eight and a half dry years from THE TRAP on TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH to my second THE WALTONS. I was ready to bring on the sobs. Incidentally the name of the script, written by talented story editor Carol McKeand, was THE GIFT. The subject of her script was death, and I felt it was an opportunity to produce a film as moving, perhaps even more emotionally stirring than HASTINGS’ FAREWELL on DR. KILDARE, filmed eleven years earlier.

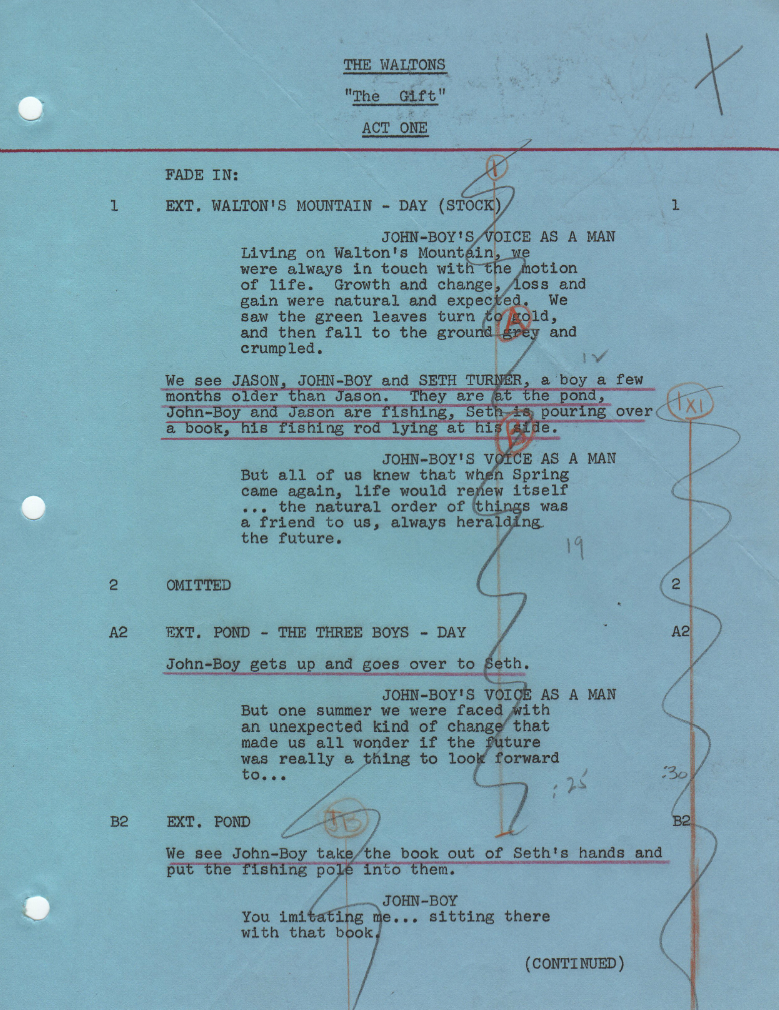

The script opened with John-Boy’s Voice As A Man over stock shots of Walton’s Mountain, followed by a sequence of the three boys fishing.

I knew that sequence would be scheduled for filming on the Warner Bros. backlot, but I didn’t want to shoot it there. I wanted air and space at the show’s opening. I remembered Franklyn Canyon, the lush location with a large reservoir lake that I had filmed several times. It was located in the heart of the Beverly Hills hills. It was expansive and green and would provide not only a better setting for the opening sequence, but there were additional scenes later in the script that would benefit by being filmed there. I asked Executive Production Manager Neil Maffeo if I could have a location day in the Canyon. He made a deal with me. He said if I could film the show in six days rather than the six and a half days usually assigned, I could have it. I immediately accepted his offer.

Casting nineteen-year old Ron Howard as Seth was easy. He had literally grown up on camera: Opie on THE ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW for eight seasons starting when he was six; the big screen THE MUSIC MAN when he was eight and THE COURTSHIP OF EDDIE’S FATHER when he was nine. But I remembered when I was on staff of PLAYHOUSE 90, casting director Ethel Winant cast five-year old Ronny Howard in one of the productions. The kid was great. The following week a PLAYHOUSE 90 production in rehearsal was experiencing difficulty. It too had a role for a five year old, and the director was unhappy with the boy who had been cast. Ethel put in a hurry-up SOS call, and little Ronny was brought in as a replacement. Quite an achievement for a five-year old — back-to-back PLAYHOUSE 90’s, the most prestigious program on television.

They let me have a big crane for the Franklyn Canyon shoot. I loved crane shots that boomed down, but cranes were also a time saver when filming on rolling terrain like in the canyon. It was easier to move the crane from setup to setup than rolling the crab dolly over the rough ground. There was a lesson concerning the crane that had been drilled into me from the first time I used one on MGM’s backlot when filming the opening sequence of JOHNNY TEMPLE on DR. KILDARE. When I was checking a setup, seated on the crane in the assistant cameraman’s seat alongside the camera operator, I was warned when it came time to dismount not to do so until the assistant cameraman was ready to take my place. Because of the counterweights if I were to jump off too soon, the camera end of the crane would fly up into the air and act as a catapult that would hurl the camera operator off into space. In my twenty-six years I never lost a camera operator that way.

Considering the scene to be played, we thought it ironic to cast Rance Howard as the doctor. Rance was Ron Howard’s father.

Seth’s home was on the Warner Bros. backlot. His run away from his home was the third sequence we filmed at Franklyn Canyon. The Franklin Canyon scenes were filmed the same day as the fishing and fainting sequences and filmed prior to the back lot scenes.

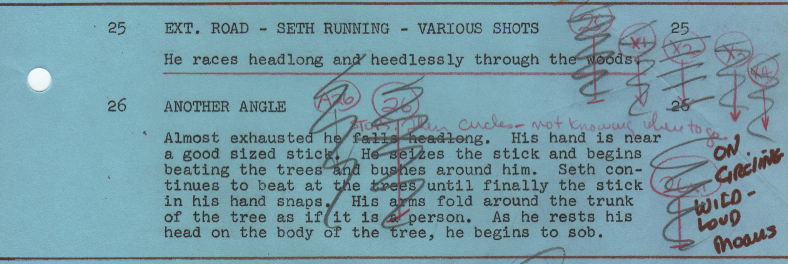

The run through the woods benefited enormously by not being filmed on the backlot. For the two-eighths of a page I filmed ten setups, although I had only planned eight. And I pushed the sequence beyond what Carol had written when I had Seth let loose with a primal scream. I pushed it beyond what ended up in the final cut. I did a full 360 degree setup as Seth circled the panning camera screaming. Carol was not too happy that I had him scream and the shot was shortened beyond what I thought was most effective.

The protagonist of this episode was Seth Turner. His story was centered in a house down the road. But the series was THE WALTONS. Stories were supposed to be about them. That’s where Carol’s script was so clever. She used the incident of Seth’s illness as a visible McGuffin, because the real story was in the Walton household; it was how the Walton family reacted when faced with the subject of death.

As I‘ve discussed before, one day during each shooting period the five adults in the cast (Richard, Ralph, Michael, Ellen and Will) would gather during a lunch hour in Bob Jacks’ office, where they would read aloud the following week’s show. Then any problems the actors had with the script would be discussed with Earl and Carol, who would do the necessary rewriting before filming began. This was done to avoid the onset delays caused by discussions for script changes. Imagine my surprise the day of filming on the Franklin Canyon location when Richard and Ralph announced they had rewritten the scene we were about to film. Their rewritten scene was the one we shot. The next day Carol was understandably upset that her scene had been rewritten.

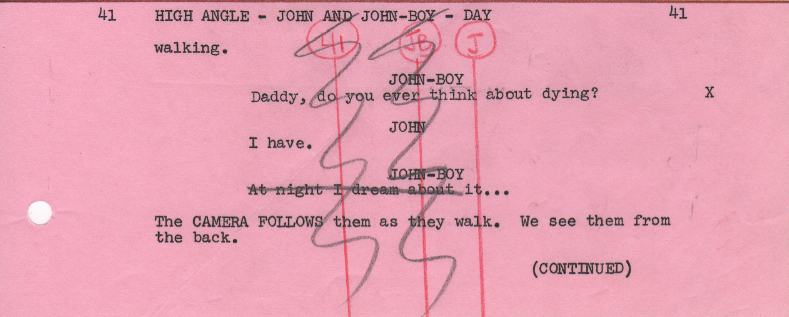

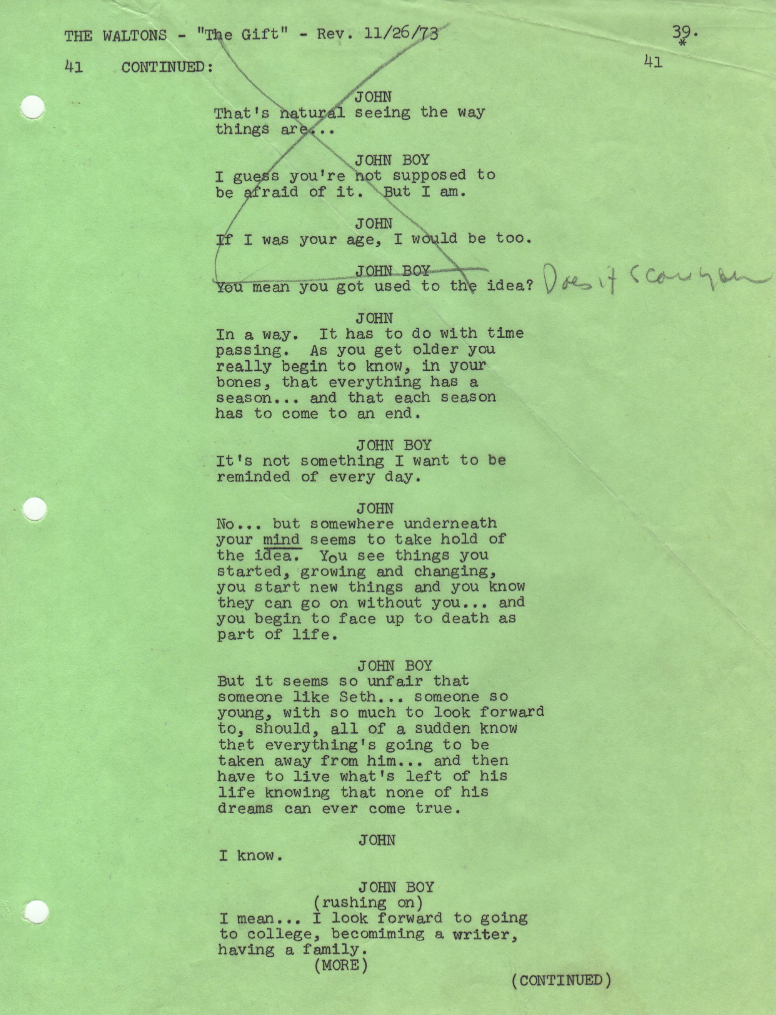

A day or so later back at the studio on the back lot Richard arrived on the set and told me he was unhappy with the scene we were about to film with him and Ron Howard. I guessed what the problem was. Ron had all the dialogue, and Richard had to sit on the swing with him and listen. Well I didn’t want a repeat of the reaction to the Franklin Canyon situation. I placed a telephone call to Bob Jacks, who came out to the backlot. I was not unsympathetic to Richard’s problem. Just as no soldier wants to go into battle without ammunition for his rifle, no actor wants to go into a scene without his ammunition — strong lines to contribute to the drama being performed. Good actors don’t just show up and recite lines. Scenes are really duels. But if there were going to be any more script revisions, I wanted them authorized by the powers above. I don’t know what happened between Richard and Bob Jacks, but after their talk, Richard reported to the set, and we filmed the scene. Ron did a sensitive job with the beautiful words Carol had provided. But thirty-five years ago it was John-Boy’s reaction that moved me to tears, and today nothing has changed. For me, with very few words, Richard stole the scene.

In Earl Hamner’s fine book, GOODNIGHT JOHN-BOY, Jon Walmsley wrote, “Ron…told me that “The Gift” was his favorite episodic performance, and that he had landed a starring role in THE SHOOTIST, John Wayne’s last film, as a result of the producers’ watching “The Gift.” I suspect Ron’s performance in the next sequence contributed to that.

The scene that Richard and Ralph rewrote was filmed on the second day at Franklyn Canyon. The perception is that the director is the all-powerful force on the set, a perception that should be a fact, but isn’t. My problem was to complete the day’s work at the location, and since it was late November, the days were shorter. This scene, which of the five scheduled sequences was one of the two that could have been filmed on the back lot, came in the middle of the day. The two remaining scenes to be filmed (Seth’s run through the woods and the opening fishing sequence) were the main reason I had requested the location. So there really wasn’t time to examine the guys’ objection to the scene as written. Plus which this was my second time at bat. Richard and Ralph were halfway through their second season. Who do you think would have won that argument? In defense of Richard and Ralph the revised pages from Carol were printed and distributed just the day before. Since they were filming during the day and did not have a chance to read the new scene until that evening, they would not have had a chance to voice their objections.

Just another case of there really was never enough time to do the work that was expected of us.

The scene between John and Seth’s father was the fifth sequence at Franklyn Canyon, although it was the first one filmed that morning. It entailed just three setups to get Red into the car. The scene in the moving car was filmed later in process.

The director of photography for the series was one of the giants of the profession, sixty-seven year old Russell Metty. His career dated back to the mid-thirties when he was a contract director of photography at RKO Radio Studio. Some of his classic credits from this period were the Katharine Hepburn-Cary Grant BRINGING UP BABY, John Barrymore in THE GREAT MAN VOTES, Henry Fonda and Lucille Ball in THE BIG STREET, Fred Astaire in THE SKY’S THE LIMIT and Ginger Rogers in TENDER COMRADE. Later he moved to Universal where he filmed the amazing TOUCH OF EVIL directed by Orson Welles and won the Oscar for SPARTACUS. He was not a physically well man. He told me he had married a younger woman, had a young daughter and made all the plans to have them taken care of if he should die. But his younger wife died first and so his concern now was to keep working to provide for his daughter.

Seth’s approaching death in Carol’s script had affected John-Boy, John, Olivia, Elizabeth, Jim-Bob, and finally Grandpa and Seth’s close friend, Jason.

The journey continues

The last scene was the best. Will Geer’s speech was so moving that it brought tears to my eyes. Entire cast and crew was excellent. I first saw Ron Howard in THE JOURNEY. I think that was his debut in the movies. He has grown up on the screen. His dad, Rance, was superb as the doctor. I just wondered if Ron was trying to get any “pointers” from you at the time?

One of “The Gift” co-writers, Jack Hanrahan, also wrote one of your ‘Insight’ episodes, “The Poker Game”, which I recently stumbled over among a collection of Youtube videos assembled by a Jeffrey Hunter fan. In that one, it appears Fr. Kieser decided to throw everything AND the kitchen sink at the audience and brought in The Dream Team to do it. Bravo to you for being at the wheel.

I think it was Peter Haskell who said as we sat down for the first reading of the script, “There isn’t another show on television that could afford this cast.”

If I’m not mistaken Franklin Canyon is also where Ron Howard and Andy Griffith shot the famous opening to “The Andy Griffith Show.” The “lake” that Opie throws a rock into is actually the Franklin Canyon Reservoir.

You’re not mistaken at all. Many, many scenes were shot at the Franklin Reservoir during the Andy Griffith Show.

Oh, Mr. Senensky. This episode was truly (pun intended) a gift…from you to us. In lesser hands, it could have turned into a maudlin mess, manipulating us into a sobfest. But your delicate touch struck just the right tone. For this, and for so much more of your work through the years, I thank you.

No Sandy, I thank you.. You cannot imagine what it feels like a year shy of half a century later to receive a message like the one you have just sent.