FILMED December 1973

The day after I wrapped THE GIFT on Stage 26, I reported to THE WALTONS’ production office to prepare my next assignment.

THE CRADLE was an ensemble piece, not only more of an ensemble piece than any I had yet directed on THE WALTONS, more of an ensemble piece than I would ever steer them through. An event would soon occur that would emotionally involve every one of the eleven occupants of the Walton home.

That was my first encounter with the delightful Baldwin sisters, Mary Jackson and Helen Kleeb. I never did ask Earl, but I always wondered if the sisters were related to Abby and Martha Brewster of ARSENIC AND OLD LACE, what with their similar propensity for concocting special spirits, although theirs proved to be far less lethal. Nora Marlowe, who played Mrs. Brimmer, was an old friend and a wonderful actress whom I had cast in earlier productions.

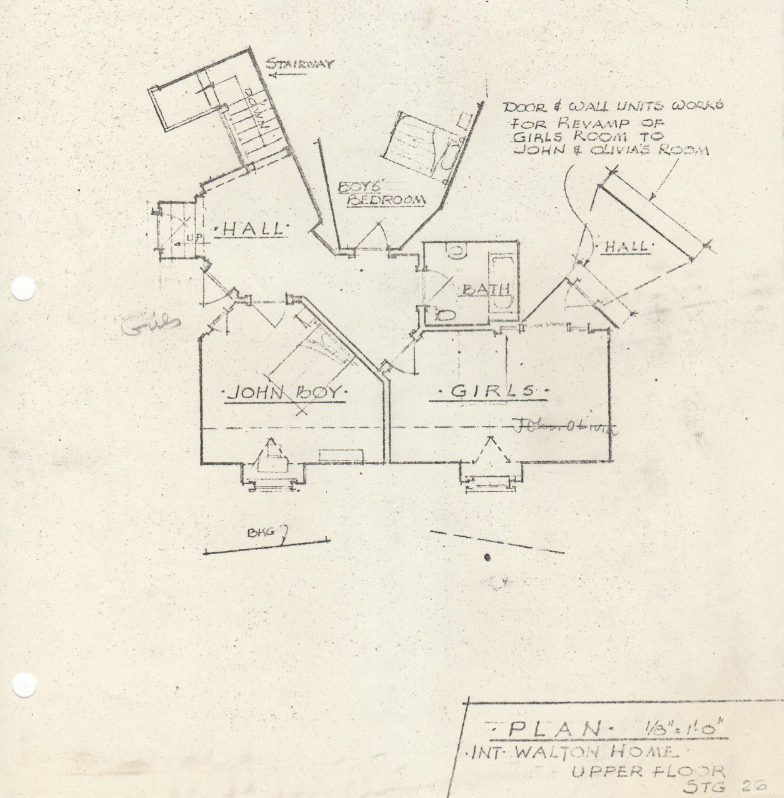

The upper floor of the Walton home presented an interesting lesson in budget accountability.

As you come up the stairway (in the upper left hand corner of the floor plan) into the upper hall, John-Boy’s bedroom is straight ahead; the boys’ bedroom is on the right, then the bathroom and finally the girls’ bedroom. The girls’ bedroom however also worked as John and Olivia’s bedroom. When we filmed IN the parents’ bedroom, the walls were revamped; a flat wall replaced the doorway used for the girls’ room and a doorway replaced a flat wall in the other corner. The view of the hall through the new door was also revamped when it was John and Olivia’s bedroom. The one change that could not be made: when filming entrances into the bedroom from the hall, both the entrance to the girls’ bedroom and the entrance to the parents’ bedroom were next to the bathroom.

The exterior of Dr. Vance’s house in this episode was the same exterior used for Dr. McIvers house in THE GIFT. The interior office and waiting room were also the same. Only the doctors changed. Victor Izay played Dr. Vance; Rance Howard had played Dr. McIvers. The depression even affected the sets.

Scenes around the dinner table presented a problem. I was never able to get a complete rehearsal of a scene because of the constantly chattering cast. But I remembered a story Edmond O’Brien had told me. In the early thirties he was carrying a spear as one of the soldiers in Katharine Cornell’s production of ROMEO AND JULIET. There were long stretches when he was not needed onstage, so he would exit his stage door and enter the stage door across the way where Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne were appearing. There he would stand in the wings and watch these two great stage veterans perform. Soon Mr. Lunt noticed this armored clad figure and would nod a greeting to him. One evening as they stood in the wings, Mr. Lunt struck up a conversation with Edmond. He asked, “How do you prepare when you’re standing in the wings waiting to make an entrance?” Eddie then tried to explain what he did, that he concentrated on getting into character, on achieving the required emotion that would be needed for the coming scene. Mr. Lunt smiled. He sauntered around Eddie as he said, “Really? I just…” and he turned and crossed out of the wings onto the stage as he spoke his entering speech. I realized there was always a wonderful interaction of the members of the Walton family in their scenes around the supper table, and if the cast was doing the same thing before the scene began, it was their way (just like Mr. Lunt) of being totally relaxed in preparation for the performances they would be giving. I quickly adapted and settled for getting the necessary information for the cameraman to light and didn’t get a complete playing of a scene until take one, which often proved to be the printed take.

Adrienne Marden (who played Mrs. Breckenridge in THE CRADLE) was a very special lady. I first became aware of her when I saw her performance of the mother in a production of William Inge’s PICNIC at the Players’ Ring Theatre in Hollywood. I didn’t meet her until a couple years later when I cast Wendell Holmes, her husband, in a production of BELL, BOOK AND CANDLE at Gilmor Brown’s PLAYBOX THEATRE in Pasadena. Eventually she played an important role in my life, but we’ll get to that later.

Adrienne made a unique and fascinating entrance into show business. She was from Cleveland, Ohio, and in 1932 at the age of twenty-three moved with her family to Los Angeles, California, relocating there because of the depression. Once on the west coast, the family searched for a new beginning. Her mother remembered an old friend from Cleveland, who years before had moved to Los Angeles where he became a talent agent in the film industry. Since Adrienne’s major in college had been theatre, her mother wondered if that might be a contact to get work for Adrienne, which would help the family’s financial problems. She looked his name up in the telephone book and discovered he had a talent agency with an office located in Hollywood. Being a fearless person she called him and he remembered her. They chatted about old times in Cleveland, about what had happened in the lives of mutual friends and then she told him of her daughter who was interested in becoming a film actress. He invited Adrienne to come see him. Adrienne took buses and streetcars in the strange new sprawling city, ending up at Hollywood and Vine in downtown Hollywood. She located the agent’s office building and took the elevator up to his floor, where she found his office and entered. He was on the phone as she came in and, without lifting his eyes to look at her, he indicated that he would be finished in a minute. When he ended his call, he hung up the telephone, stood up to greet Adrienne but stopped dead in his tracks, a startled look on his face. Wanting to see her right profile he ordered, “Turn to the left.” The equally startled Adrienne did as she was instructed. “Turn to the right.” Again she complied. “Incredible!” he said, as he came around his desk, grabbed his hat and said, “Come with me.” Adrienne was shocked. She had heard the stories of Hollywood agents and casting couches. She didn’t move. “No, it’s all right,” he said, “we’re going to the studio.” He took her arm as they rushed out of his office, descended in the elevator to the garage where they got into his car and drove for miles to enter a maze of large forbiddingly gray concrete buildings. They entered a large office where the agent instructed her, ”Sit down. Wait for me here,” as he disappeared into one of the inner offices. Shortly he returned with a man, who said, “Stand up,” which Adrienne did. “Turn to the left.” Then “Turn to the right.” And again, “Incredible!” The two of them then led Adrienne into a larger office and again they instructed Adrienne, “Sit down. Wait here,” as they went into an inner office. They shortly reappeared with a third man. Again, “Stand up. Turn to the left. Turn to the right. Incredible.” Then the three men, with Adrienne obediently following, left that building, walked a long distance past towering studio soundstages and entered another building and a very impressive office. Again “Sit down. Wait here,” and the three men left the room. When they reappeared, the three had become four. Again it was the newcomer who said, “Turn to the left. Turn to the right. Incredible.” Then as he headed for the exit with the other three starting to follow he added, “We must do a test.” Adrienne finally spoke up. “No.” The four men stopped in their tracks and looked at her. “I’m hungry,” she added. “I haven’t eaten since lunch. It’s late.” A sandwich was quickly ordered, after which Adrienne was taken to the makeup department, where a makeup man worked on her face as a hair stylist did her hair. She was then taken to the wardrobe department, where she was outfitted with a beautiful gown and then down to the soundstage where she was placed before a camera and with glaring arc lights blinding her eyes, a film test was made. “Turn to the left. Turn to the right.” But this time no “Incredible.” Only after the test was completed did her mother’s agent friend tell Adrienne what was happening. She was at the illustrious Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio where a film, RASPUTIN AND THE EMPRESS, was in preproduction. The film was to star the three Barrymores, Ethel, Lionel and John. Still to be cast were the young czarinas, the daughters. The reason for the screen test? Adrienne bore a remarkable resemblance to Ethel Barrymore, who was to play the Empress, and in the following few days when the screen test was viewed, she was cast in her first major motion picture. When Adrienne told me this story, she remembered vividly her first day of filming. She was on a huge, elaborate ballroom set, dressed in a magnificent gown, her hair and makeup having been done by experts, surrounded by hundreds of glamorously gowned extras, when a hush fell over the set. At the far end of the soundstage Adrienne saw three figures enter – the stars of the show, the three Barrymores. She was fascinated as she watched them move through the ballroom. Then she became alarmed as she realized that with Ethel in the lead, followed by Lionel and John, they were heading toward her. The towering Ethel Barrymore arrived and stared at Adrienne. Finally, “It’s true. You look exactly as I looked when I was your age.” And Miss Barrymore spun around. “Come Lionel,” and she stormed off, followed by her bemused bother. John watched her leave, then turned and leaned into Adrienne. “It’s true. You do look like she looked, but you’re a hell of a lot better looking.” Then he moved off, leaving a confused young girl waiting for her first close-up.

Adrienne played one of the three young czarinas. It was a small role (uncredited) with few lines, but it was one of the most prestigious films that year from MGM, not a bad way to make a film debut. Her two sisters were played by (also uncredited) seventeen-year old Jean Parker and fourteen-year old Anne Shirley (still known as Dawn O’Day). Adrienne told me her role was mostly decorative, but she had one dramatic scene with a couple of lines when the Empress and her daughters were hiding in the cellar, waiting for the revolutionaries. There was to be a tight two-shot of Miss Barrymore and Adrienne as the Empress comforted her frightened daughter, which was when Adrienne had her dialogue to speak. As the camera rolled, Miss Barrymore placed her hand behind Adrienne’s head and pulled her face into her bosom. Not only was Adrienne unable to deliver her lines, not only was she barely able to breathe, her face was not visible in the shot. Fifty-three year old Ethel Barrymore had no intention of appearing in a tight two-shot with a face thirty years younger than hers that was a reminder of how she used to look.

After BELL, BOOK AND CANDLE Adrienne and Wendell sort of adopted me. I was often a guest at their home in Santa Monica. They were interested and came to see the stage productions I directed. Then in 1959 they told me that members of Actors Equity on the west coast wanted to bring to the west a project that the guild had sponsored in New York – Equity Library Theatre. Since I was a member of Actors Equity (although on withdrawal) because of my employment in the Chicago and Florida stock companies, I was eligible to submit a project to the committee to be directed by me. I eagerly jumped at the opportunity and made my selection. I submitted Maureen Watkins’ CHICAGO as the play I wanted to do. A few days later I was notified the committee had approved my submission. Then a couple days after that Wendell (who was on the committee) called again, this time with somber news. CHICAGO was not available for production. The play had been written and produced professionally in 1923 and had been an enormous success. But playwright Maureen Watkins had been unhappy that the production had turned what she had considered a serious drama into a comedy. She withdrew the play from any future theatrical productions, although it did make it to the screen a couple of times. That banishment stayed in force until the Bob Fosse musical version in 1975. It was suggested that I find another play to submit. At that point I rebelled. I had really wanted to do the production of CHICAGO and the disappointment at this latest development put me in a deep pit of discouragement. It had been five years since I had returned to the west coast. I had been involved in thirteen theatrical productions during that time in addition to my full time labors at CBS. Suddenly it all seemed so futile. Which was when Adrienne stepped in. If I wouldn’t pick another play to do, she would. She suggested Paul Osborne’s MORNING’S AT SEVEN. I knew the play. I felt it was exactly the kind of gentle play I didn’t want to do. I had already directed productions of DEATH OF A SALESMAN, THE CRUCIBLE, THE ICEMAN COMETH and with fine reviews they hadn’t gotten me the attention I sought. But Adrienne was persistent, so I finally agreed to submit it to the committee. I don’t know what happened at the committee meeting when my submission was discussed, but I think Wendell’s knowledge of my reluctance to do the play may have affected their decision. They decided against MORNING’S AT SEVEN and selected THE LADIES OF THE CORRIDOR that had been submitted by John Erman. Once I had been rejected, I had second thoughts about my decision, but what was done was done. Then a few days later I received another phone call. The committee had been notified that THE LADIES OF THE CORRIDOR was not available and MORNING’S AT SEVEN had been approved. I’ve already related the final outcome of that situation, but to recap: it was a huge success. Norman Felton, an executive at CBS took notice, I went with him when he left CBS to go to MGM to produce DR. KILDARE, which was my launching pad. And all of it happened because Adrienne Marden wouldn’t accept my reluctance to pick another play.

Michael Learned was only twelve years older than Richard Thomas, but there was no problem accepting her playing his mother; and it wasn’t because she looked old. I think it was because of a wonderful quiet maturity and authority that she seemed to exude. Michael was not always front and center as she was in THE CRADLE. Many times Olivia’s presence in a scene did not include dialogue. And I think that in the later years of the series that sometimes became a problem for Michael, which is perfectly understandable. No actor wants to feel excluded, to feel that without dialogue to contribute he is no more than a dress extra in a scene. But I found that even without dialogue or with little dialogue, Michael contributed enormously just by her presence. A few years later I directed a scene between Michael and Beulah Bondi in which Bondi had the bulk of the dialogue. The night the show aired, when that scene was on the screen, Beulah Bondi was heard to utter, “She’s stealing the scene.” That’s screen presence!

The journey continues

Great story about Adrienne Marden… I think Wendell Holmes died really young and then Adrienne was married to Whit Bissell for a while… love these stories Ralph… keep’em coming

Actually it was the other way around. Adrienne was married to Whit Bissell first, for sixteen years and he was the father of their two daughters.

It may have been an ensemble episode, but Kami C. got some quality film time. 🙂

Ralph, did Earl H. ever talk about the 1971 Waltons TV movie that preceded the series? The movie had almost a completely different cast for the main adult parts: Andrew Duggan as John, Patricia Neal as Olivia, Edger Bergen as Grandpa, Woodrow Parfrey as Ike Godsey, and David Huddleston as Sheriff Bridges. Even both Baldwin sisters were re-cast. Only Ellen Corby was kept for the TV show. I’m guessing economics was one reason for re-casting the John and Olivia roles.

I, too, noticed how youthful Michael Learned looked compared to Richard Thomas…unrealistic, but how can I complain when my favorite movie (‘North by Northwest’) had Jessie Royce Landis (born 1896) playing the mother of Carey Grant (born 1904). But, casting Michael was the right move. Aside from her acting, she and R.C. Edwards brought some much-needed glam (understated, of course) to Walton’s Mountain.

I never discussed THE HOMECOMING, the TV film that gave birth to THE WALTONS with Earl. He does discuss it in his fine book, GOOD NIGHT JOHN BOY. Usually when a pilot film is made, contracts for the series are included in the negotiations. THE HOMECOMING was not a pilot film. It was a TV movie that was so successful that a series was an afterthought, so that there were no contractual negotiations with the actors in the film for any services beyond the movie. I wonder if economics was involved in casting the role of the father. Earl tells in his book that Henry Fonda was contacted (he had played the father in SPENCER’S MOUNTAIN, the earlier WB film based on Earl’s book about his family and Fonda did not work cheap). However they arrived at the cast, it was a great group.

I think the entire cast was perfect for the TV show. I was about Erin’s age and the Walton’s were my extended family as I am sure many others also felt. (smile)… As far as John Boy and Michael being only 12 years apart. Then she must have looked a couple of years older than her true age, and Richard must have looked a couple of years younger than his true age, because I never noticed.

Best TV show there ever was, and I might add, for a while not to long ago, I started having bad dreams at night, but I found if I recorded The Walton’s and would watch an episode right before bed, I had good dreams instead of bad ones… So I guess one could say, that show is good medicine… (smile)

Penny

Ralph, I watched your “Snow Job” episode of ‘The Rookies’ on Youtube and was surprised to learn from the closing credits that Adrienne Marden played the broken-down old lady!

Indeed she did.

Hi Ralph

The Waltons has & always will be my fav show to watch may it be repeats I have been watching the show for many yrs ecer since I was young & will continue to watch it, No matter how many times I have seen the show I will watch. I love the Easter story, & The episode “The Vigile” Where grandma Walton gets sick & MaryEllen thinks she knows whats wrong with her. I could say a lot more but to sum it up I will always watch The Waltons & the Waltons special movies “The Thanksgiving Story about John-boy getting hit with the saw mill fan belt. It’s very sad that you all cast members lost the 3 most very important people on Waltons Mountain Grandpa & Grandma Walton & Ike Godsey Joe Conely. I’m hoping some day that I will get to meet the whole cast members of the show. Im a Special Needs person Im in the Special Olympics bowling & Bocce ball 18 yrs now & also take pottery classes on Tues. Ralph if you are ever in Denver Colorado,,,Aurora city & county of Aurora Colo I would love to meet you. I know you once had a tv show I cant remember the name of the show but I remember something about a boat & boat docks. Anyways hope to hear from you sometime have a great day I will always keep watching The Waltons

Your fav Walton fan

Laura Spears

Hi Laura: How nice to hear from you — and such a heartwarming message. THE WALTONS WAS, IS and ALWAYS WILL BE one of the favorite series with which I was associated. It is so gratifying to know that over 40 years later, it is having as great, even a greater response from viewers.

Ralph

I have watched the Walton’s ever since they first aired. My Dad was the one who made it a family affair to sit and watch it every Thursday night as that was the night it came on in Lamesa Texas. You put on an episode today and I can tell you everything about it as that’s how many times I have watched over and over and over….I still watch it today and I am 57 years old…..

I love the Walton.s I have been watching for a long time ,all of them are a blessing. B

I have watched the Walton.s for a long time . it.s a family show .I love the sister.s and the recipe. thanks for all you all do B

Over here in the UK, The Waltons is just as popular as in the US.

I had a difficult childhood but always found escape during an episode. No matter how poor the family were, or how tough things got, they always got through it and I used to imagine my life like that as well.

Now I’m grown and in charge or my own destiny as it were, I always watch the programme when it’s on, can never get enough!

I’ll never tire of The Waltons, I can remember the elation I felt when it came on the TV and I could forget what was going on around me for an hour…

Xxx

Yes, the Waltons… in 1975 in Germany from 1975 on the television to see…

I bought the seasons on DVD… Unfortunately there is not all episodes complete in Germany… still a lovable series…