Filmed February 1985

TCM’s The Essentials recently aired George Stevens’ 1948 classic, I REMEMBER MAMA starring Irene Dunne in an Oscar nominated performance. At the end of the screening Sally Field, Robert Osborne’s co-host, stated that movie sadly would not be made today. She said it was labeled ‘a woman’s movie’, and that label was meant to be derogatory. In today’s entertainment market movies like that are considered weak. Robert Osborne added that most of the new movies he sees today are action movies.

I applaud them for daring to voice that incontrovertible but seldom stated fact, that there is a serious paucity of meaningful films about women, half of our world’s population. But it is not a new lack. It has been affecting our screens both big and smaller for many decades. I especially appreciate their statements because I liked directing stories about women. In my early career directing film I had a few opportunities to do it. In 1962 I directed two episodes of DR. KILDARE that could be considered ‘women’s films’: THE MASK MAKERS with Carolyn Jones and HASTING’S FAREWELL with Beverly Garland. In 1963 I directed two more for ROUTE 66: IN THE CLOSING OF A TRUNK with Ruth Roman and NARCISSUS ON AN OLD RED FIRE ENGINE with Anne Helm. And then the gender drought set in for me, a drought that lasted over two decades. In 1985 executive producer Lynn Roth wrote a story and turned it over to Susan Miller to write the teleplay. The project was called THE BIG D. It was commissioned to showcase the enormous talent of Lainie Kazan, and it was assigned to me to direct.

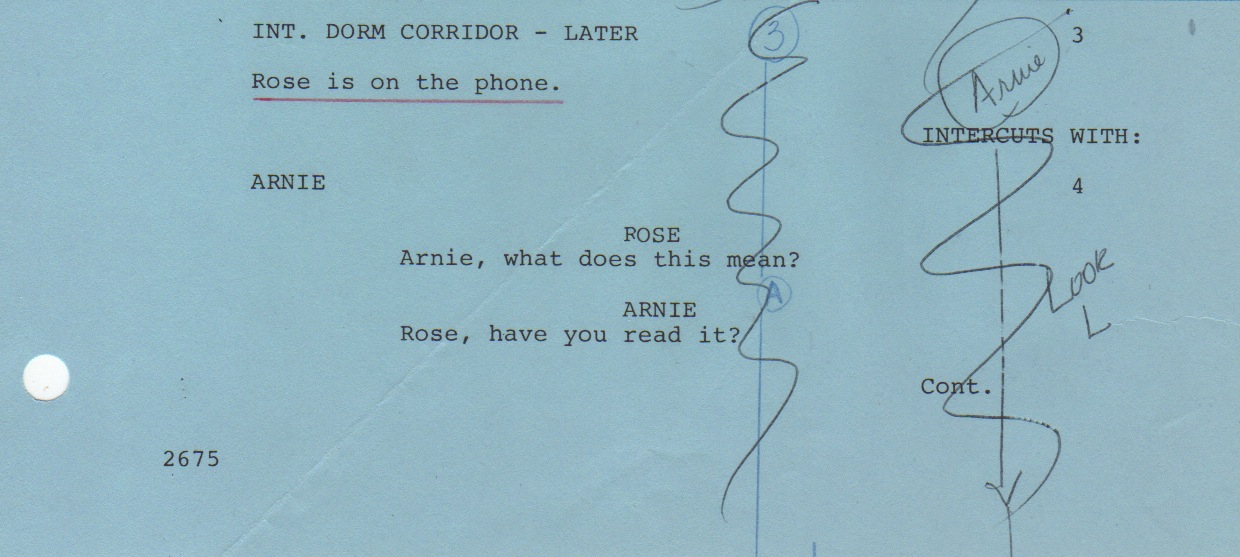

The next scene was a phone call between Rose and Arnie. It was scripted in the usual way …

… intercutting close-ups of the two people conversing.

I told Lynn that I wanted to play the entire phone conversation on Rose, just hearing but not seeing Arnie. She said she wanted to see intercutting close-ups of both people, so that’s what I filmed and what was edited. After the film was assembled, it was sent over to Showtime for their approval. They had one request. They thought Arnie should not be seen in the phone call, that it should be played just on Rose.

THE BIG D was scheduled to be filmed in the usual six days – 5 days of interiors at the studio and one day on location at the University of Southern California.

There were so many factors involved in building the schedule board. Take the one day we were to film on the campus of the University of Southern California. Normally if there was an exterior night scene to be filmed, we scheduled it on a Friday, because of the benefit of the weekend regarding turnaround. Our scheduled first and sixth days were Fridays, but we would never schedule a location for the final day of filming because of the possibility of inclement weather. The University had restrictions on which days filming on campus was available. We went to the University on Monday, our second day, and it was a heavy day. There were 8 sequences totaling 9 pages. 9 principal actors were involved, 7 of those sequence were day sequences, and we were filming in February when the days were shorter.

Phil Sterling (attorney Ben Fine) was another in the enormous pool of talented Hollywood character actors. THE BIG D was the third time I worked with Phil. Great acting is not what happens when the actor is hitting his marks and saying his lines. It’s what happens on his face, in his eyes between the lines. Phil came to the table with a full plate.

Sidney Walsh (Rose’s daughter) was an example of exceptionally good casting. Not only was she a very fine actress (unknown to me before working with her), but she looked like Lainie. She could have been Lainie’s daughter

Question: How many lawyers does it take to screw in a light bulb?

Answer: How many can you afford?

Shades of Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland! Starting in 1939 with BABES IN ARMS, they made four musicals in which two teenagers gathered their friends together and put on a show in their backyard. Our young people were no longer teenagers, but beyond that I think the analogy holds true. The courtroom can be a form of theatre. In this case we just wouldn’t have Lainie Kazan sing.

There was a general practice in series with large running casts of having stories with parallel plots. When the plots collided at the finale, it worked fine, but most of the time the two plots were unrelated. That was the case with THE CHOICE, my first THE PAPER CHASE. The main plot of the young couple with the question of “to abort or not to abort” had nothing to do with other students’ nervousness over attending the faculty tea. THE BIG D had a single thread plot that stayed focused on the emotional turmoil of Rose Samuels. Well, it did make an intriguing adjustment. It expanded with the involvement of Rose’s fellow students into what could have been retitled, ANATOMY OF A DIVORCE.

John Houseman’s career was truly unique. The profession was loaded with successful actors who moved behind the camera to direct: Laurence Olivier, Clint Eastwood, Barbra Streisand, John Cassavetes, Jerry Lewis, Gene Kelly, Warren Beatty, Robert Redford, George Clooney. John spent many years backstage and behind the camera as producer, writer, director. At the age of 72 he not only starred for the first time in a film, THE PAPER CHASE, he won an Academy Award for the performance and then spent the following 15 years continuing to act.

One day mid-afternoon production manager Jack Oliver came onto the set. When filming was completed on the scene before the camera, he assembled the crew for an announcement. He said that federal narcotics agents had come onto the lot and were on the set of the Lee Majors’ series, THE FALL GUY. They were conducting a thorough search for drugs. Without stating it the implication of his announcement was clear, and there was an immediate scurrying around before we returned to our subject of divorce. The federal agents did not come to our set.

I have heard for years that in television there was no time to rehearse. I didn’t agree with that. I always rehearsed. Well, almost always. As an example of the almost always, consider the following scene, 2½ minutes with only Rose on screen and talking. Since she was seated throughout the scene and there was no camera movement involved, I kept the rehearsal to an absolute bare minimum. In doing a scene like that I always wanted to be sure the camera was rolling when the actor’s emotions kicked in. I was rolling camera on what would normally have been a dress rehearsal. We got through it, and I called for take 2. Lainie was magnificent. At the close of the scene I said, “Cut, print,” but Lainie asked to do it one more time. I was satisfied with what we had, but you never know. Maybe she could be even better, so I called for take 3. Since Lainie was already so emotionally involved, the performance on the third take was over the top. That was our final scene for the day, and as I left the set Lainie was still sobbing. Take 2 was the performance that was included in the film.

There was an unexpected advantage in not cutting to Arnie in the earlier telephone call. Like Laura (whose reaction was, “and that’s Rock Hudson?”), the audience’s image of Arnie was as Rose recalled him, and the contrast between what she recalled and his present image added insight to her continued love for him.

Walter Brooke (Arnie’s attorney) as an actor was a chameleon. I had known Walter since 1952, when I was the assistant director at a summer stock company in Wheeling, Illinois (a community north of Chicago). Walter was appearing in a touring stock production starring Franchot Tone that came to our theatre, and I stage managed it for the run. I was a twenty-nine year old in his first professional job, and Walter, already a seasoned pro, talked to me like an equal. He told me he had been one of the two final contenders for the role of Biff in the screen adaptation of Arthur Miller’s DEATH OF A SALESMAN. It was between him and Kevin McCarthy, the decision to be based on who was cast as Willie Loman. When Fredric March won that role, Kevin was in and Walter was out. I knew Walter and his wife socially on the west coast. Later in 1985 I directed a production of YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU at Theatre 40 in Beverly Hills. Walter and his wife came to see the production, and I cherished his comment to me afterward. He said ‘the direction was seamless.’ Walter died the following year.

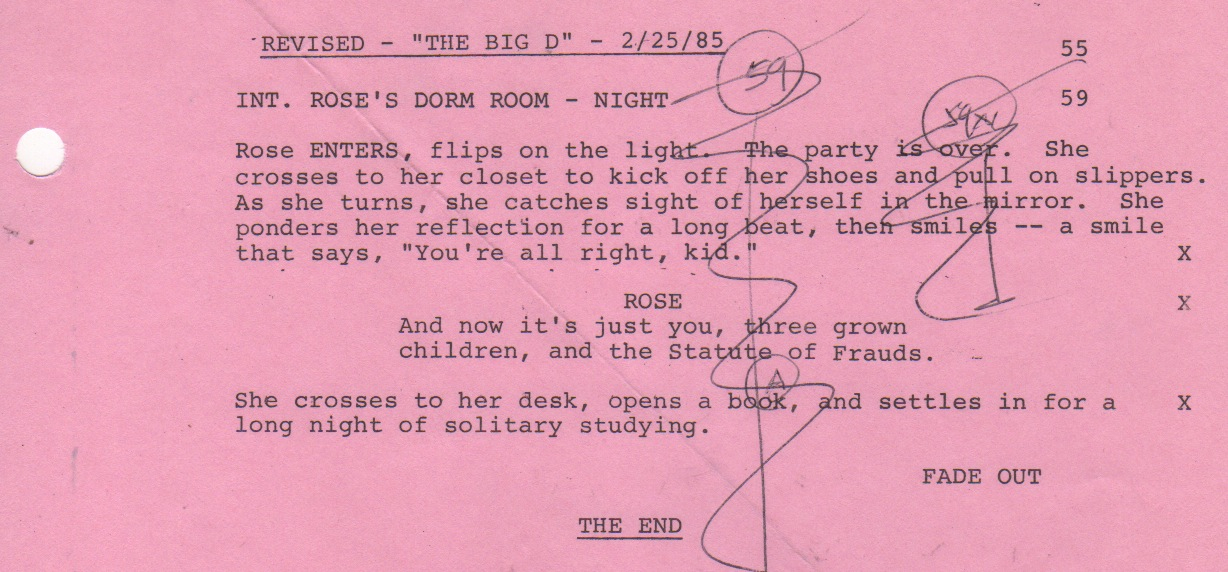

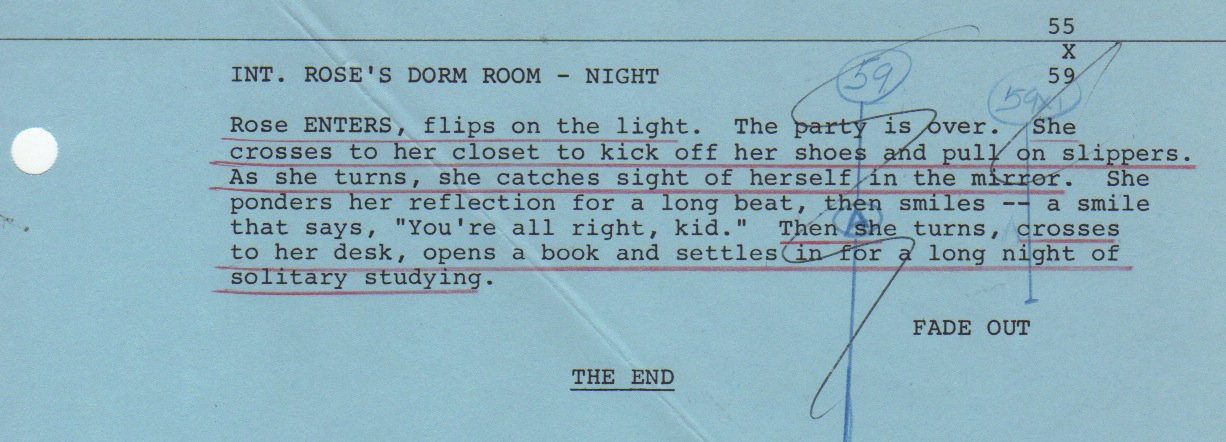

As I’ve reported somewhere in my previous PAPER CHASE ramblings, Lainie had understudied the role of Fannie Brice in the Broadway production of FUNNY GIRL. I liked the opening of the FUNNY GIRL movie when Fanny on entering the theatre, catches sight of herself in a mirror and says, “Hello gorgeous.” The final scene of our film had only half of that — Rose looked at herself but just nodded …

… but I felt she should speak. I don’t demand happy endings, but I believe strongly in positive endings. I relayed my feelings to Lynn, and on February 25 a revised page for that scene was published. We filmed it on February 27. I was satisfied. Her words to her image in the mirror added closure to her last toast: ‘to a new beginning,’ and I had my homage to FUNNY GIRL, another strong lady, the legendary Fanny Brice.