Filmed June 1966

With the commencement of the 1966-67 season there had been some major changes in the personnel structure of the QM Production Company. I again want to stress that my knowledge of this was strictly that of an employee at the lower rungs of the company ladder, like the awareness of a soldier in the front lines of the realignment of generals and colonels at the upper end of the echelon. John Conwell the previous year had cast 12 O’CLOCK HIGH and had overseen the casting of THE FUGITIVE. He did that with the title of Assistant to the Producer. Now with the addition of the third series, THE FBI, John was elevated to Assistant to the Executive Producer and in that position he oversaw the casting of all three series. Bert Remsen was assigned to cast THE FBI. Bert was truly a profile in courage. He was a very fine actor who had had a tragic accident on a film set when a camera crane fell on him. There had been many, many surgeries (and there would be many more); Bert at this time was severely impaired and with great difficulty walked with two canes. I thought that John and the QM organization were to be highly commended for keeping Bert in the profession by converting him into a casting director.

The changes in the organization didn’t stop there. Arthur Fellows, who had held the position of Assistant to the Executive Producer, was now designated as In Charge of Production. I’m sure Arthur was fulfilling the same duties but with a more impressive title. And the changes still didn’t stop. A new figure was imported into the company. Adrian Samish, a former executive at ABC, was now added to the QM staff and he too was designated as In Charge of Production; he would be in charge of preproduction and would oversee the scripts, while Arthur would continue to oversee postproduction. I learned some of the staff were perplexed by Adrian’s recent addition to the company. There was a suppressed feeling that his sojourn at QM Productions might be a temporary arrangement, that a private deal between ABC and Quinn Martin might have been made for Quinn to take over Adrian’s contract as a means of ABC’s terminating him. All of this conjecture turned out to be false. Adrian joined the company and stayed with it until a decade later when it ceased operation.

Under my new contract with QM Productions I immediately started prep on THE ASSASSIN the day after I completed photography on THE ESCAPE. The parentage of the new script was diffuse.

To interpret the information on that credit card:

Teleplay by John McGreevey with the Story By credit underneath meant that McGreevey had been hired to rewrite a script that had been deemed unacceptable and had changed enough in his version for him to be given total teleplay credit.

Story by Anthony Spinner meant that Spinner had been given the original assignment but had turned in a script that was found to be deficient, but the final rewritten script retained enough of the original story structure that Spinner was credited with Story By.

Add producer Charles Larson into the mix. Charles (like Gene Coon) was an enormously gifted writer who managed to put a final polish, (many times of major proportions) on the scripts that crossed his desk. And like Coon he rarely took screen credit for his efforts. Having directed scripts by all three men, I detected Charles’ fine handprints all over THE ASSASSIN, the best script I had yet been handed on THE FBI and eventually the best one of the series I would ever direct.

The Manila embassy and street were on the backlot of Warner Bros. studio. That assassination scene provided another justification for me to have insisted on the right to be in the editing room. Marston Fay, the editor, in assembling the sequence of the killing used only the shot across the gun from inside the van as the man fell and the vehicle drove away. I also wanted the second shot of the body falling in the foreground as the van is driving off. Marston didn’t argue the point, but he did think it was unnecessary.

We decided very early that we wanted Dean Jagger to play the pacifist, Bishop John Atwood. An Academy Award winner for his performance in 12 O’CLOCK HIGH, Jagger had not appeared in any film since the end of his series, MR. NOVAK, two years before. (I vaguely remember that there might have been some illness during that period.) He showed up at the studio several days before the start of filming for the usual wardrobe fittings; but he also wanted discussions about the role. He was like a young colt prancing to get out of the starting gate. He was excited, anxious and I think a little nervous.

For the role of Atwood’s friend, Dean Sutherland, I wanted the wonderful Rhys Williams. Rhys earlier that year had appeared in an episode of THE WILD WILD WEST that I directed. He had been a Hollywood fixture since his debut in films in 1941 when he arrived from England (he was born in Wales) to appear in John Ford’s classic, HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY.

Appearing as the security guard was a very solemn and somber Ted Knight, just four years before he cast all that seriousness aside to join THE MARY TYLER MOORE show.

At that time there was the network of giant talent agencies in Hollywood: William Morris, MCA, Ashley Famous Artists (en route to becoming ICM). They handled the big, big stars. Then there was the tier of smaller but fine agents who handled respected feature players. I knew some of those agents because they would drop by my office to chat and make suggestions: Lou Deuser of Deuser-Armstrong Agency, Billie Greene of Greene-Vine Agency, Alex Brewis of his own agency. Alex would regularly drop by my office at QM, seeking work for his clients. He had some very talented people, many young ones just starting out. Alex had been touting a young Tom Skerritt to me for some time. There just hadn’t been a role that he was right for. This time there was. We hired Tom Skerritt to play the idealistic young college student caught up in the cause.

The casting of Anton Christopher, the assassin, was a very interesting journey. My first choice for the role was slightly built, blondish David Wayne. He proved unavailable. John Conwell then suggested George C. Scott. Now this was not in line with my concept, but I had worked with George and who could say no to casting him. But he too proved unavailable. I then suggested Gig Young, dark-haired but at this point in his career mainly a light comedian. It would be three years later that Gig would win an Oscar for THEY SHOOT HORSES, DON’T THEY?, definitely a non-comedic role. But he also was not to be had. John along the way had suggested Fritz Weaver. I thought Weaver was a fine actor, but he was exactly the dark-haired ‘heavy’ image I was trying to avoid. I said no. I had seen an actor in one of the John Houseman produced theatre productions at UCLA (the group that eventually metastasized into the Mark Taper Forum) who filled my original vision of the role when I sought David Wayne. He was William Windom. Bill had been around for a long time, a very working actor in television starting back in the live days in New York. There were no great objections to him, but there was no great excitement either. Then John called me one day and said if we wanted Fritz Weaver, we would have to decide right now because he had another offer pending. I again said, “But I don’t want Fritz Weaver, I want William Windom.” And I got William Windom.

There was a glaring director’s error in that scene. I didn’t catch it at the time, but it has bothered me every time I have viewed it since. Anton, when he took the dead pilot’s pulse, left his thumbprint on the wristwatch. Was that a clue for the FBI? But nothing came of it. My goof.

The very first scene on the first day of filming was between Efrem Zimbalist and Dean Jagger. This was Dean’s first time in front of a camera in a couple of years and as I wrote before, he was as nervous as a young actor facing his first job. As we began rehearsing and then filming, that nervousness was very much in evidence, but not for long. It was amusing that it only took a couple of takes and Dean, confidence now restored, in his enthusiasm was kindly making suggestions to Efrem about his role. Efrem looked at me with a knowing smile. It was great to welcome this Academy Award winner back to where he belonged — in front of the camera.

Billy Spencer was an artist who painted with light. He had won an Emmy the previous year for his black and white photography on TWELVE O’CLOCK HIGH. Now he was filming in color and his photography was magnificent, because he lit it the same way he lit black and white, with cross lighting. One of the things I had learned working with Billy was that when the camera moved into the set, that hampered what he could do with his lighting. He had to avoid casting shadows of the camera or the sound boom. Richard Haman had designed a beautiful set for Dean Sutherland’s home. I told Bill I had staged the scene with the camera staying out of the set, that he could go ahead and paint to his heart’s content.

The scenes of the FBI at work often provided a challenge. They were usually filled with exposition, agents spouting, “just the facts” and most of the time doing it over the telephone. There was a limit to how visually interesting scenes like that could be shot. This script had a scene between Erskine and Rhodes that avoided that trap. Richard Haman provided a simple set with wonderful hanging light fixtures and Billy Spencer did a masterful job painting a pure film noir sequence with his lights. The page and three quarter scene, which according to my usual frame of measurement could have required an hour and forty minutes to film five setups, was completed in a little over an hour filming only three setups. I made it easy for the film editor too. All he had to do was cut off the slates of the three pieces of film and make two splices.

In an ideal movie world schedules would be set so that films would be shot in sequence; on the first day start with the beginning of the story and continue through so that on the last day the final sequence would be filmed. That didn’t happen in feature films. It certainly didn’t happen in television. The difficult situation I found myself in was that a strong climactic scene in Anton’s hotel room was the final scene to be filmed on the FIRST day of production. It was the first scene in which Bill Windom and Tom Skerritt were involved. What was even more difficult for me was that I had never worked with Bill Windom or Tom Skerritt before; we were total strangers when we met on the set that afternoon.

When series episodes went into syndication, there was a good and a bad. The good was the residual income; the bad was that further cuts were made in the shows to provide room for more commercials. The scene above was cut from those early syndicated airings. This was disturbing to me, because I felt it was one of the most effective scenes in the film. I had strong feelings about Anton’s line and Bill’s delivery of it, “I was fourteen, the bartender was my father, my first and last crime of passion.”

The standing sets for the offices of the FBI were extensive and elaborate. Since so many of the scenes of the activities of the Bureau were telephone conversations, I wanted to do more than show closeups of two people at their desks with telephones held up to their ear; I wanted to present the picture of an active and thriving organization.

If the production schedule started off with the difficulty of my having to do a major scene on the first day between Anton and Hastings, it did provide an eventual advantage. Having filmed the first three pages of Anton’s hotel room Friday afternoon, Monday was devoted to completing the other ten pages in that location, eight of them additional scenes between those two main characters. And those scenes were sequential. It was almost like doing a one-act two-character play. It was intense and exciting.

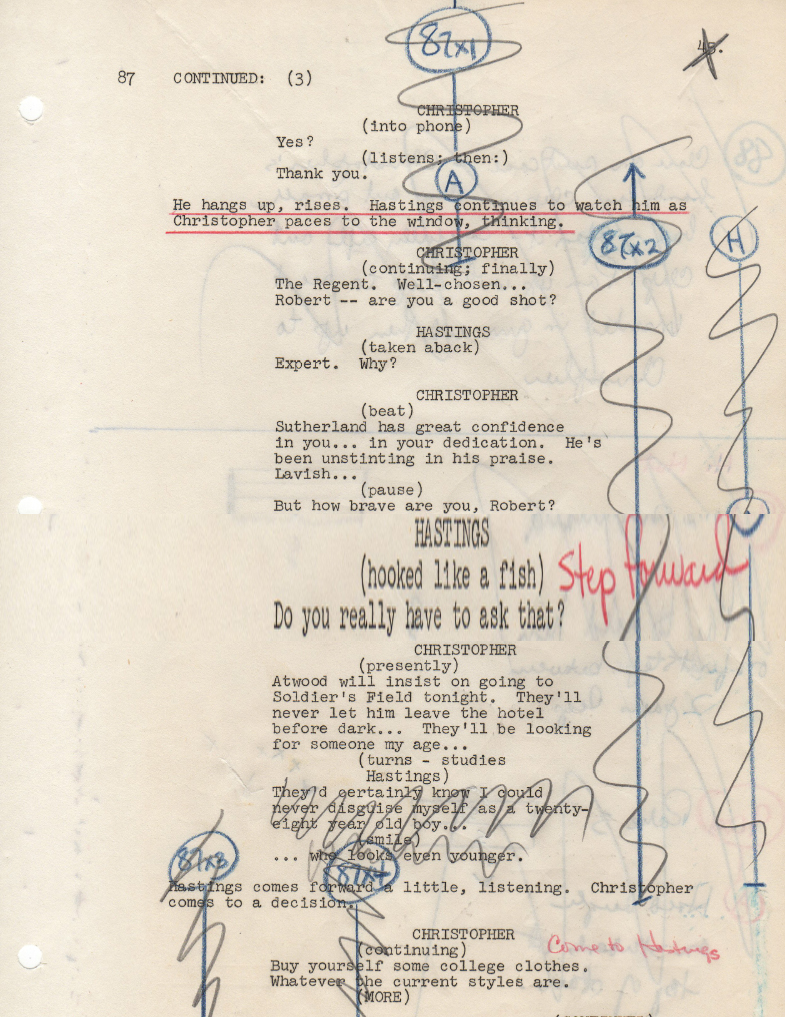

One day during the preparation period Charles Larson called me into his office. He seemed perturbed as he told me he had just received a memo from Adrian Samish with notes on THE ASSASSIN. We went over them one by one and found them to be minor criticisms that could be corrected without doing any damage to the script. But then there was a note on the scene when Anton turns the act of assassination over to Hastings. Adrian said he didn’t feel there was any justification for Hastings to agree to Anton’s proposal. I was disturbed. I liked the scene and had no doubt it would play. Charles agreed with me. He told me not to be concerned. It was fixable without harming it. He said he knew that Adrian was an avid fisherman. He was going to add a simple stage direction before one of Hasting’s lines. He would write in, (hooked like a fish). And that’s the only change that was made.

Bill Windom, whose performance I think dominates this production, completed all of his scenes in the first three days of the seven-day schedule. Arthur Fellows, who never came to the set, did drop by on the third day of filming after he had viewed the rushes of the scenes in Anton’s hotel room. He told me, “I am fascinated by the dailies.”

It was great to work with Bill. As a director I tried never to tell an actor how to play a scene. If I had any critique, I couched it in an analysis of the situation. Very early on I did this when working on a scene with Bill. He listened to me and then, with a twinkle in his eye he said, “You mean you want me to talk slower.” As I remember it, my response was, “Yes, I want you to be more like Alan Ladd in THIS GUN FOR HIRE.”

Charles told me that the following day when they viewed the rushes, Quinn expressed surprise and wonderment that in a screening room, watching dailies he had shed tears during the final Atwood-Erskine scene.

In the original script the final scene of Anton’s arrest came at the end of Act IV. The epilog that followed was a meaningless wrap-up scene. To avoid making any cuts for time in the main body of the show I suggested to Charles that the arrest be the epilog. He agreed.

The day after THE ASSASSIN aired on October 9, 1966, John Conwell told me he had a slew of telephone calls congratulating him on his casting of William Windom as the assassin. He very graciously said he had responded that the credit belonged to me.

The journey continues

This is my favorite episode of The F.B.I. among those which you’ve directed.

Mine too.

Great casting of William Windom as the assassin. He was marvelous in a menancing way. He gave the character depth and feelings that I didn’t expect. In the epilog, I felt he was all “played out,” and just seemed glad he was captured. He could have run, but he just stayed there waiting for the FBI. His heart wasn’t in the game anymore. Wonderful, exciting, classic episode! Bravo again, Ralph!

Ralph, just wanted to weigh in here and say how much I love reading your dissections of these classic TV episodes. This is exactly the kind of thing I wish we could do more of at the Paley Center for Media. Really fascinating to read your posts, which I think are further evidence of how so many people tend to undervalue the craftsmanship that was involved in creating episodic television during the post-live-anthology days.

I’ve just heard about the passing of William Windom. He was such a great actor. You were fortunate to work with him on numerous occasions. May he rest is peace.

“No great excitement” after you asked for William Windom? Wow…well, he just finished doing three years of a sitcom (‘The Farmer’s Daughter’). Who could imagine a clean-cut Minnesota congressman bumping off three people in an hour?! It’s called acting! I liked him more in your ‘Mission: Impossible’ episode, but more on that later.

Besides “out-Shatnering” Bill Shatner in ‘Star Trek’, do you know what else I like about WW? His voice – it cuts through the air effortlessly with volume and clarity. In this day of an aging population with less than perfect hearing, it’s a valuable quality. In contrast, My Dad and I watched the 11th video and we could not figure out what Tom Skerritt said from 0:54 thru 1:03 without replaying it more than once.

Tonight at 10:30 PM, Antenna TV will have WW’s 1971 episode of ‘All in the Family’, which is priceless. I flipped on that channel the other day and caught the last five minutes of his first ‘Barney Miller’ appearance – he was wearing a belt of dynamite sticks in the police squad room!

Speaking of 1971, IMDB says he had THIRTY credits that year (14 TV series eps., 8 TV movies, 3 feature films, 3 talk show eps., and 2 game show eps.). He also did an ESSO gasoline commercial!

And with all that talent, he was a charming, unassuming, totally professional actor with a great sense of humor. He was a joy to work with.

Wonderful, informative post Mr Senensky,

William Windom was one of my favorite actors – as you know, he was in everything and continued his superlative performances all the way into the 90s with his role in Murder She Wrote. I remember seeing an interview of him discussing his work in the late 50s and 60s and he said whenever they needed an actor who could cry, they would call “Willie the Weeper” – I’m sure he was being modest – I thought he had great range and could perform any role that came along, and I had forgotten he was an Emmy winner for his role on My World and Welcome to It. Very nice to know he was as nice a person as he was talented as an actor.

You may have saw this already – it’s a Star Trek Fan based site that stages their own productions – William Windom appeared in this episode along with Barbara Luna……..http://www.startreknewvoyages.com/?page_id=336

You got great performances from everyone in this episode – the scene you mention above between Mr Zimbalist and Mr Jagger – the first scene Mr Jagger performed in several years – I thought was brilliant, riveting acting on his part – what a pro……..

Pingback: William W. Spencer: ‘Artist who painted with light’ | The Spy Command

William Windom is one of my favorite “unsung” actors of all time. Everything I have ever seen him in was elevated by his performance. He was imminently “watch-able”.

Even his thankless role in the “Columbo” pilot was a joy to behold.

He will be missed.

Pingback: 6 Mantras That Mattered - Ralph's Cinema TrekRalph's Cinema Trek