Filmed January 1967

STAR TREK was a phenomenon. I directed six and a half episodes of the original series, working a total of ninety days. I worked many more days than that on just the pilot of DYNASTY. I directed twice as many episodes of THE WALTONS and two and half times as many episodes of THE FBI; I directed more episodes of THE PARTRIDGE FAMILY and more episodes of THE COURTSHIP OF EDDIE’S FATHER than I did of STAR TREK. And yet today if you google-search my name on the internet, you will think I spent most of my career directing STAR TREK. So although STAR TREK was five years after I began my journey in film, let’s begin our trek into the past there.

How and when did this phenomenon involve me? It was early December, 1966, when one of my agents called to ask if I would like to direct an episode of STAR TREK. I had not seen the show, and I was not into science fiction, but I also was not one to turn down a challenge, so I said, “Yeah, go ahead and book me.” They did, and the studio sent me a script, THE DEVIL IN THE DARK by Gene Coon, which was scheduled to be filmed in early January, 1967. I liked that script a lot. I then packed my bags and flew back to Iowa to spend the holidays with my family. A few days after my arrival I received another script from the studio with a note telling me that they had switched scripts, and I would be directing one called THIS SIDE OF PARADISE. I was disappointed. THE DEVIL IN THE DARK was a strange, eerie script, totally different from anything I had directed, while THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, although it was science fiction, was not really new territory for me. It was a bittersweet love story. But the die was cast, so I went to work on the new script.

After the holidays I returned to the west coast and reported to the Desilu studio to prep. Desilu was the old RKO Radio lot at Melrose and Vine where Katharine Hepburn had made her first film and where Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers had danced their way into our nation’s heart. Our first order of business was casting. For Leila we cast the exquisite Jill Ireland, and for Sandoval, the leader on planet Omicron Cetti III, Frank Overton. The biggest problem facing us was finding the locations, the buildings of the colony. There was neither the time nor the money to build sets, so we were faced with the problem of finding something standing that could serve our purpose. Our search of the area produced only one possibility, the Disney ranch, and to use that we had to do some creative rationalizing. The buildings on the ranch certainly did not look like they belonged in the STAR TREK century. But what if the settlers on this planet went to the past for their architectural inspiration — back to early Americana. Good idea? It had to be; there was no other choice.

To start filming we were scheduled for three days at the Disney ranch. The first two days went swimmingly. We completed over eight pages each day, were right on schedule, and it all seemed as if I was just filming a rustic love story, the only difference being that the guys were dressed in funny suits and one of them had funny ears. Then came day three. We reported to the ranch as usual in the dark so that we would be ready to film with the first light of day. But before the first light got to us, the news did that Jill Ireland (who had not worked yet) would NOT be reporting to the location; it was feared that she had measles. We then went to work, completing all the scenes at the ranch that did not include her, after which we packed up, moved back to the studio and finished the day filming on the Enterprise. The next day we learned Jill did not have measles and would be returning to finish the show. However we hit a new snag. The Disney ranch was no longer available; it had been booked by another film company. The fortunate thing for us was that all of the scenes that involved buildings at the ranch had been filmed, so arrangements were made for us to complete our location filming in Bronson Canyon, an area in the hills conveniently close to the studio.

I was amazed then, and now inching toward a half a century later I am still in awe of those studio magicians, who in answer to a request for a ‘garden’ in the middle of a pristine green hilly landscape could fulfill my request, and on such short notice.

This was my first film with cameraman Jerry Finnerman, and it was the beginning of a friendship that has lasted over forty years. Jerry later told me that it was the following scene that made him sit up, take notice and decide that I was a director he really wanted to work with. That feeling was reciprocated.

Sometimes things do work out for the best. What may seem like a misfortune can actually be a boon. Bronson Canyon turned out to be a more idyllic setting visually for the remaining location scenes than the Disney Ranch would have been.

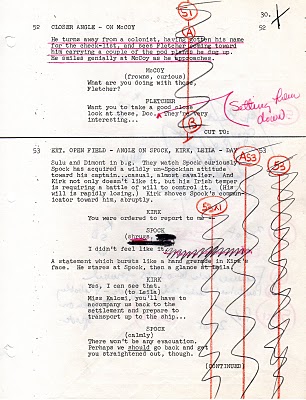

There was a first for me on this production, and I think a last. I had a scene blocked, lit, rehearsed and ready to shoot, but I was not happy with the way it was playing. To forestall any possible other recollections of what occurred, here is some archival evidence. First the script for the scene. You will note scene 53 is set in an Exterior Open Field.

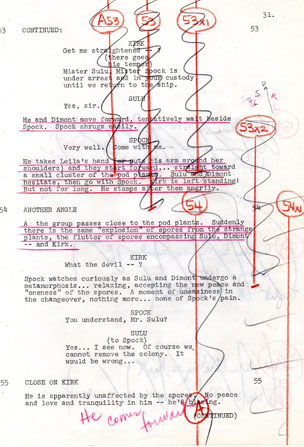

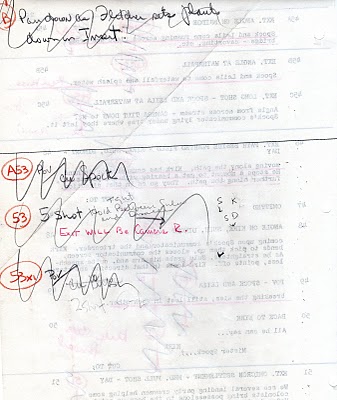

My pre-planned staging for the scene shows that I had planned a five-shot in the middle of the field.

Fifty yards away I had spotted a very inviting limb.

I asked Jerry if we could break the set-up and move to another location. He readily agreed. So we moved everything the fifty yards and filmed what has become a classic scene of the series.

Spock’s character was not the only one drastically changed by the spores. Dr. McCoy, after his encounter with the spores (and a few mint juleps) suddenly emerged with his southern charm intact, embellished by Georgia-born DeForest Kelley’s original sho nuff accent.

When we completed our location filming in Bronson Canyon, we returned to the studio to shoot the interiors of the settlement and the Starship Enterprise. Jerry Finnerman, director of photography, was a master at lighting. He had learned his craft from a giant in the film industry, Harry Stradling. Jerry was the assistant cameraman on Stradling’s crew, and then he became Stradling’s operator. His closeup of Jill Ireland in her first scene in the film I think is a master work. For his final step in lighting her closeup Jerry placed a small baby spot directly behind Jill’s head. Her movements had to be totally restricted or the lamp would show.

When Kirk returned to the Enterprise, Jerry not only lit the set beautifully for the mood of the sequence; he used light changes in Shatner’s close-ups to illustrate visually his emotional feelings.

When staging fight scenes, stuntmen were usually used in the wide shots, with the principal actors doing the closer angles. As it turned out in the struggle between Kirk and Spock, the set was not large enough to shoot a wide enough shot to totally conceal the substitutions.

One of the important lessons I learned when directing theatre was that when doing comedy look for the serious moments, and when doing drama, look for the comedy. Spock hanging from the tree limb like a monkey was an injection of comedy into this serious drama. And Kirk’s final line, “Had enough?” was, I thought, a fine comic touch to end a scene of violence.

With the crew back on board, the love affair over, all that Spock has to do was participate in my favorite final scene of the STAR TREK episodes I directed.

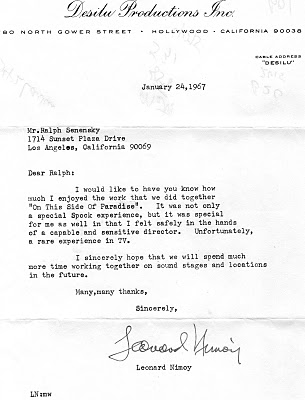

After production had finished, I received a very nice note from Mr. Spock.

I was no longer disappointed that THIS SIDE OF PARADISE had been substituted for THE DEVIL IN THE DARK. What I didn’t know at that time was that an even stranger and (I thought) better script than DEVIL (also written by Gene Coon) would be my next STAR TREK assignment.

The journey continues

Loved the whole new set up and your rendition of the Star Trek love affair makes me wonder why I never watched the series so long ago. I wasn’t a fan then, but I am now.

One of the great aspects of the original Star Trek was it’s great blending of drama and comedy. And of course putting contemporary issues into science fiction. I think Dorothy Fontana’s script for “Paradise” was excellent. She reworked Jerry Sohl’s original story into something much more meaningful. And she was promoted to story editor after this assignment.

Loved the behind-the-scenes information on one of my favorite “Star Trek” episodes! Thanks so much for sharing with us!

LOVE the new format.

Look forward to each and every new episode.

Congratulations and thank you

Peter W

Love the new format.

Great work, and thank you in advance for many more.

I was great to read what goes on a television production. Especially a great Star Trek episode. Thanks!

What wonderful recall you have, Desilu was a special time in television history.

And your work with this show has become timeless and part of the lexicon that is fine science fiction drama.

Thank you for your insight and clearly your framing of shots is second to none.

I enjoyed this episode, but I heard that there were many female fan letters protesting Spock’s having an affair with a woman. They liked his cold, unemotional logic. They felt it made the show compared to Kirk’s and McCoy’s emotional reactions. After this episode I don’t recall Spock’s involvement with other women. Please set me straight on the real story, Ralph!

I did not know of the fan letter protests. I never had any problem with his new behavior. After all he was half human. The spores had released him and freed his emotions to respond as a human. He of course reverted in the end to being a Vulcan, but he was now very aware of what was missing in his life when he said, “For the first time in my life I was happy.”

I just recently found your website and though I have only met you once in person, Jay has talked of you often, I look forward to learning more about you and your journey through the films and shows you directed.

Isaac Asimov wrote: “It hadn’t occurred to me that Mr. Spock was sexy… that girls palpitate over the way one eyebrow goes up a fraction; that they squeal with passion when a little smile quirks his lip. And all because he’s smart! If only I had known! If only I had known!”

Joke aside, J.J. Abrams’ recent Trek movie “solved” this problem and presented a love affair between Spock and Uhura. I think it’s all wrong! Spock’s character was interesting because of these contradictions present in this episode, and in many others. That he even can’t told his mother he loved him, not speaking about women like Leila. Abrams ignored this, and made him a much simplier character, losing all the great edges and conflicts he had in the original series.

Dear Ralph,

I was only 11 when Star Trek began and I loved it and watched it religiously; though much of the third season was hard to take.

Now thanks to Netflix I am able to see and study the shows. I saw the excellet This Side of Pardise just the other day.

Naturally one sees things much differently as an adult. I was so stuck by this episode that I wanted to seek you out and thank you for your fine work. Jerry Finnerman was indeed a master. I’m going look for the work of Harry Stradling too. Together you made one of the very best Star Trek episodes ever. The ending is superb and launches Mr. Spock into our hearts, at last a full equal from then on to Capt. Kirk.

Hope you are well. Thank your for your generous sharing of the details of your work.

Dear Ralph

I enjoyed this episode. Especially for the performances made by the late Jill Ireland and Frank Overton(who died shortly after this episode was filmed).

Thanks for directing the best of Star Trek. They get better and better with each viewing.

Love this episode, too. Those plants still kind of creep me out. Might be the music reused from the Talosians. Another great Kirk story AND a great Spock story. Hard to do. I love the one Act Out where Kirk says, “This is mutiny, mister!” and Mr. Leslie says, “Yes, sir. It is.” Was it true that Charles Bronson was on set to keep an eye on Jill Ireland? I love this website. So cool to revisit stories I know so well and see them through your eyes and with your input. Thanks again!

I don’t know where the story of Charles Bronson being on the set started. As far as I know, no, he wasn’t. Or if he was, he was being unrealistically quiet.

Ralph,

I’ve just stumbled here via a link from the ClassicTvHistory blog. Fascinating stuff, these behind-the-scenes details. The final scene clip gave me a bit of a shiver — I knew Spock’s line, but had not watched it in too many years. Superb stuff, and your close-up on him really makes it work.

Ralph, at startrek.com they have one-minute episodic previews from The Original Series. I assume they were made by Paramount to promote the series in the ‘60s. The one for ‘This Side of Paradise’ includes a scene of Spock and Leila walking down to a small stream filled with rocks. From what I’ve read elsewhere, it was the prelude to a love scene (also filmed?). None of it was in the finished episode. Can you add anything more to this? Thanks.

I have checked my script. There were three shots of Spock and Leila on a bridge and cavorting by the water that were shot but ended up on the cutting room floor because of time. They came after the love scene and before the scene where Spock swung from the tree branch like a monkey. Many times extra footage that did not make it into the film will be used for trailers and publicity.

Marvelous. I have dined like a gourmet on your behind-the-scenes story of This Side of Paradise, for many decades one of my very favorite Star Trek TOS episodes of all time. Obviously all the exteriors were dubbed, because otherwise there would be birds and insects (not to mention, perhaps, traffic and wind) on the soundtrack. Frank Overton and Jill Ireland were pitch-perfect as rebellious “flower children” in a far off solar system.

The only thing that bothered me a bit was Spock’s explanation of where the Spores came from…he said “They drifted through space until they finally landed here.” Which of course was totally unnecessary. It would be much more credible if the spores just came from the biology of Omacron Ceti 3.

I think this was certainly the best of the “counter-culture” stories in Star Trek’s universe. Thanks a lot.

The only thing I must contradict: the exteriors were NOT dubbed. That was a good sound crew, and if there was a sound disturbance on any take I would call for another take.

Mr Senensky – thank you for all of your recollections of working, not only on TREK, but all the other classic – and not so classic – shows you worked on. PARADISE also has the wonderful scene where Spock beams Leah up, and she realizes he has gone back to normal. The small, wistful smile Spock manages at the end of it is classic.

One question, if I may: One of the many strengths the original TREK had, in addition to the talented writers, performers, producers and technical people, was Roddenberry’s insistence of using the best directors out there. People like yourself, Joe Pevney and Marc Daniels. I am sure that you ran across Daniels and Pevney occasionally; what can you tell Trek fans about them. To me, Daniels is the interesting one – here is a the guy who gets very little credit, but is as historically important as any. He did as much to help launch I LOVE LUCY as anyone, establishing how a three camera sitcom would be rehearsed and blocked. He was perhaps THE pioneer of live TV drama. He was a key in pioneering the corporate televison program. And on top of that was as busy a director in the 60’s as there was – doing both comedy and drama, and working almost up to the day he passed. Can you shed any more light on him? Thanks in advance, and thanks again for your talent and memories!

I knew Marc better than Joe. And I so agree with what you say about Marc and I LOVE LUCY. I used to take special pleasure if I bumped into Marc socially, and as I introduced him to my companion, I would say to her,”Do you want to see a grown man cry? Ask him how much he made in residuals from the first season of I LOVE LUCY” (when I think he directed most if not all of the episodes). The amount of course was $00.00.

I found your site on a reference regarding Stephen Brooks, whose portrayal of a young ensign in Obsession, I was very impressed with, but quickly found that your body of work and insight on so many television series that I remember very well, but slightly pre-dated my conscious foray into the magic box ( i was born 1969). As a professional photographer, I was very interested in your acknowledgement and insight on the techniques of your Director of photography, Jerry Finnerman. As a young teen I was able to run around the Paramount lot as my stepfather worked under Eddie Milkus, who I believe was part of Star Trek: TNG in early pre-production of the series, but pulled his name off before the original pilot. Regardless, I am thrilled to have found your memories, and will be back to study more of this era in television. I love Star Trek, but I have not watched these episodes in a few decades. To stay on point, I can see why Nimoy would write you this letter as you allowed him to give a stunning unforgettable performance, and your memoirs certainly share the respect with the TEAM that made this era in television remarkable. If I had one question, it is that I was always surprised that ST only lasted 3 years, you directed your share of Star Trek episodes, enough to proudly be a solid part of its success without argue, so with your insight, would you say the Desilu restrictions were crucial in bringing down the show? When I watch these early episodes, with an older eye, and fresh perspective, it is remarkable to watch how this ensemble worked together, and how well the writing and directing was. TNG was given years and a fan base already in place for the actors to seem to get not just in total sync but stride, but ALL of the original Star Trek cast, well, they are incredible to watch, from 1st episode. I look forward to working my way through your body of work, and appreciate your commentary.

Eddie Milkus indeed was a vital part of the STAR TREK team. I wonder if I knew your stepfather. As to your surprise that ST lasted only 3 seasons, if you read my other STAR TREK posts, I comment on how I saw the situation. To recap it it in brief, I felt the decline came with the sale of Desilu to Paramount Studios (then owned by Gulf Western). The high quality of the series was established the first year and a third when Desilu (under the stewardship of Herb Solow) produced the series. It was the Paramount restrictions that lowered the quality in production, so that by the end of the third season Paramount and NBC agreed the time had come to put an end to its run. The network had always been unhappy with the low ratings and had cancelled the show at the end of the first season and again at the end of the second season, only to restore it to the schedule after the onslaught of fan’s objecting mail. The refusal of STAR TREK to die is (IMO) one of the amazing stories in television.

Hello. I enjoy the episode about the space spores. Was Leonard Nimoy and Charles Bronson was involved in a conflict during/after the filming of the episode?

I have been asked that question before, and I again say that to the best of my knowledge the answer is no. I am sure if Charles Bronson had visited the set that Jill would have introduced him to me. That didn’t happen.

Loved this episode, it’s my favorite one. I grew up a few blocks away from Ralph’s brother in Mason City, Ia and when I heard from Ralph’s niece that he was directing Star Trek I simply could not believe it. I must have been about 11 years old. It was just to much information for me to process at the time. Sorry Lisa, you were right!

Hi Ralph

Been chatting w/Marlyn Mason recently ’cause I’m a fan and she mentioned your blog. Told her I was a devout Star Trek addict back in the day and she said I should make a post on your blog showing my appreciation. Indeed, anyone who had anything to do w/the original series are legends of the universe! 🙂

“Damn it Jim, I’m a doctor, not a bricklayer er psychiatrist er physicist er escalator er mechanic er engineer er magician er coal miner …”

Ralph, take care and “Live long and prosper!”

Hello. I like the episode that you help to write, but I wondered how the plants would reproduce and thrive in the planet’s environment.

First off I love your remembrances of your time in the industry. I wish more directors and crew would do the same, I find the technical aspect to putting together a television show or motion picture quite “fascinating”. Regarding this episode specifically, I was 8 years old when this one first aired. Loved it then, because of the emotion, humor and adventure that you, the cast and crew infused into it, that and I wanted to be Captain Kirk. Again watching it (repeatedly) as a teen in the 70’s I began to realize and appreciate the direction, the writing and overall production. As corny as this sounds, being a child of 60’s, 70’s television it were those in moments in Star Trek, the Waltons that helped form the desire(courage) for me to pursue many of my dreams, engineering,stand up comic and actor and (the hardest job) a father. So thank you Ralph for contributing to a legendary and iconic television show(s) which I know inspired many others beside myself, after to all isn’t that what a great storytelling is supposed to do.

To which I have to respond and say, “THANK YOU!”

Ralph, long time no see.

I always wondered, if let’s say in 1987 Gene Roddenberry or Bob Justman called you up and said, “Ralph, we’re launching a brand new series this year called The Next Generation. We’d like to ask if you’re interested in revisiting the old Paramount lot to direct an episode (or more) for us?”, what would’ve you answered?

If I had not seen any of the new series, I probably would have said yes. If I had seen (as I did early on when THE NEXT GENERATION aired) the new series, I probably would have said no.

In going over your fascinating blog, I see that you directed the two episodes that each contained a line that made a subtle reference to “Star Trek”‘s occasional problems with NBC. In this one, after McCoy comments “That didn’t sound at all like Spock,” Kirk comments “I thought you said you’d like him better if he loosened up.” “I never said that” McCoy protests. This little exchange mirrors an event described at length by Harlan Ellison in his forward to the printed edition of his unedited teleplay for “City On the Edge of Forever” where, when the show was in development, NBC tried less alien looks for Spock. After the show’s-and the character’s-success, NBC suppressed all evidence of this until Ellison secured a photo and presented it to the befuddled executives, who reacted much the way McCoy does. And coincidentally, in “Bread and Circuses” to encourage Flavius:

Master of Games: “You bring this network’s ratings down, Flavius, and we’ll do a special on you!” This I’m sure accurately reflects at least some network’s executives’ feelings about Roddenberry and his “low-rated” sci-fi show!

Thank you Ralph for creating this golden archive of your past work and the accompanying illuminating insightful commentary. These are the shows I grew up on; the shows that made me want to be an actor. To be able to revisit these episodes and read how they went down has given me a quick link to the process that I can only glimpse when I am working on a set. Thank you. And thank you again for your solid work over the years.

Mr Senensky, just discovered your blog and as others have stated here, let me say how much I enjoy your in-depth accounts and insights of all the wonderful series I grew up with in the 60s – they’re a real treasure – and I learn something new from each post. I’m hooked……..

For this one – I especially enjoyed your account of Jerry Finnerman’s use of the baby spotlight behind Jill Ireland’s close-up – I would have never noticed it – I just remember the unique ethereal and angelic like quality of the scene, and now know why……..

Hi Ralph…I just discovered your site today. Excellent. Thanks for sharing memories of not only “Star Trek” but all the other wonderful productions you’ve been associated with.

Just curious, have you ever done a “Star Trek” convention and what was your impression of it if you did.

Each of the “Trek” episodes you directed really resonated with me. I will echo what some others have said about the music of George Duning. He really brought a dynamic score to episodes like “Metamorphosis”, “Return to Tomorrow” and one you didn’t direct, “The Empath”.

I would say both George and yourself are two of the unheralded “masters” of “Star Trek”.

Why is a TV show with only 79 episodes from the 1960’s still studied today…because of the concepts explored, the high level of craft and talent on display and of course, the written word.

Thanks Ralph for entertaining us for more than 50 years now. Your notes on these episodes are most appreciated.

ps…I will add that “The Partridge Family” is now being replayed on “Antenna TV” and it is a charming sitcom from a much simpler time. You’re right that Danny Bonaduce had incredible timing and delivery for being a kid actor. He had “it” much like how David Cassidy had “it” for being the “teen idol”.

To answer your question: No, I have never attended a Star Trek convention.

To add to your later reflection: I agree with all three of your reasons why STAR TREK, its 3-year mission cut down from its original 5-year intended mission by some very misguided people, is actually more popular today than when it originally aired: the stories presented REAL people. The special effects were there to enhance the people in the forefront, not to STEAL THE SCENES. The productions were geared to make viewers think and feel, not to titillate them with false thrills.

Hello Ralph,

Thank you for sharing your stories about the making of your wonderful Star Trek episodes. I really love how certain chance elements and occurrences came together to make the episodes even better than they would have been otherwise.

During my latest viewing of The Side of Paradise I noticed Spock does something odd with his fingers while pointing out a dragon in the clouds. It seems almost to qualify as a sort of invocation. It is during the scene where Spock is laying across Leila’s lap in case you wish to review it yourself. Spock’s finger movements seem very precise, even choreographed. I was hoping you may be able to shed some light on this interesting bit of business. Spock could have just as easily pointed in a casual manner–in fact it would have been easier for him to have done so. I’d love to know whose idea it was, and what it was meant to indicate. Thank you in advance for any insight into this little enigma.

All I can say is, that was Leonard. Everything he did he carefully choreographed. That’s why he was so good. No, good doesn’t do it. He was better than that!

Ralph,

I just watched This Side of Paradise for I don’t know, the 30th or 35th time. I was watching a modern TV show that’s pretty good, but I just wasn’t getting into it and I realized I had the urge to watch some Trek. Looking through the playlist this episode called to me, and I’m so glad I watched it. Did Leonard Nimoy ever had a finer hour as Mr. Spock? There must be 5 or 6 moments when Spock’s world is turned upside down, and you can sense how his head is spinning, but Nimoy (under)plays it so perfectly that it just makes it all the more powerful. It was the perfect episode to watch in the wake of Leonard Nimoy’s passing.

This Side of Paradise has everything everyone loves about Trek, and you put it together masterfully. You and DC Fontana and Nimoy all deserved Emmys for that episode.

Thank you so much for your many outstanding contributions to this timeless, universal TV series.

DC Fontana thanks you, Leonard Nimoy thanks you, and I thank you for those wonderfully encouraging words!

Pingback: TVC 3/13

Pingback: TV CONFIDENTIAL Show No. 269: Tribute to Leonard Nimoy

I love this story.

Hi, Mr. Senensky:

I had the immense pleasure of watching “This Side of Paradise” once again after many years and felt compelled to see who the director for the episode was. I was so thoroughly happy to see your website and learn more about your life and work. Thanks so very much for sharing your talent and following your passion and profession with such integrity. This website is a great resource for anyone interested in persuing a carrer in film and television industry.

Thanks again.

Sincerely,

Karim Miteff

It was 50 years ago today that “This Side of Paradise” started filming on January 5, 1967. Amazing just to think about it. Half a century and the show is still going strong, thanks to the marvellous talent in front and behind the camera.

I totally agree! I’ve been looking for a service that would email or tweet “50 years ago on this date, filming began on…”, but haven’t come across one yet.

Along those lines, I believe the next episode to being filming is Ralph’s “Bread and Circuses”, starting in 12 days (minus 50 years)…

(“You may not understand because you’re centuries beyond anything as crude as television.”)

Actually I didn’t start filming BREAD AND CIRCUS till the following summer. METAMORPHOSIS came first.

Pingback: Right Next To The Dog Faced Boy | Professor Wagstaff

Thank you for sharing your wonderful memories, Mr. Senensky. I love your incorporation of the notes you scanned, including the one from Nimoy. How special! Earlier tonight, I also enjoyed your comprehensive interview with the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences.

I find “This Side of Paradise” one of the most beautiful episodes of Trek. It’s probably my favorite TOS episode second to “The Menagerie.” I’m curious– How was the collaboration with the performers? Were there any on-set revisions to the story? How far did the creative process extend for you?

Also, what is your personal belief or reaction toward the concluding exchange between Kirk and McCoy? McCoy said, “Well, that’s the second time man’s been thrown out of Paradise.” Kirk replied, “No, no, Bones, this time we walked out on our own. Maybe we weren’t meant for paradise. Maybe we were meant to fight our way through, struggle, claw our way up, scratch for every inch of the way. Maybe we can’t stroll to the music of the lute. We must march to the sound of drums.” This is a profound, staggeringly thought-provoking moment. If you have the availability and interest, I’d love to hear your take on it and how this line of thought may or may not personally resonate with you.

Thanks again for lending your artistry to such a beautifully told, endearing story. Many blessings!!

And thank you Wes for your response to what I did 52 years ago. As I wrote, PARADISE was my first introduction to STAR TREK. And it was near the end of the first season when STAR TREK was still a Desilu Production. There were no on-set revisions in the excellent script by D.C. Fontana. The only major change in staging was the one I described that ended in Spock hanging from the tree. As for the dialog in the concluding scene about the exit from Paradise, I thought it was beautifully expressed and as I stated, Spock’s final line, “For the first time in my life I was happy.” was my favorite closing of the 7 STAR TREKs I directed.

And like you, THIS SIDE OF PARADISE is a favorite, but second (and here we disagree) to my METAMORPHOSIS.

This episode is one of a few where every aspect comes together to produce some of those special moments in TV that are sometimes matched but never exceeded.

One sometimes comes across such special moments in film, theatre, sport, family, TV, etc.

This episode has some of those moments.

My favourites ?

” I can love you ”

” For the first time in my life I was happy “.

Your work will be appreciated and admired as long as there are people to watch it.

Many thanks for your contribution to this classic.

BJ: I hate to be repetitious , but I say to you what I said to Wes up above: thank you BJ for your response to what I did 53 years ago. (I changed your name for his and I added a year to the intervening years.)

Hello again, Ralph:

I’m 60 now, and Star Trek has been in my life for 55 of those years now (my Dad was a big sci-fi fan). And of all the episodes I’ve seen and how many times I’ve seen them, THIS episode contains the only ST scene that ever made me tear up, when Jill Ireland breaks into tears that she was losing Mr Spock again. Thank you for the moment!

Ralph, I only just discovered this website and, having just listened to your discussion of the show on the “Enterprise Incidents” podcast, I wanted to take a moment to thank you for the work you did on Star Trek. I’m yet another 50+ year-old who has been enthralled by Star Trek his entire life, so forgive the duplicative nature of this comment but it’s great that I have a way to tell you after so many years of watching and re-watching Star Trek how much I appreciate you and your many contributions to shaping my heroes! Your imprint on the franchise will always remain and be appreciated by generations to come.

Dear Mr. Ralph Senensky,

Fantastic stuff to read and revel in after watching so many of these sensitive episodes. “Metamorphosis” and “Obsession” were always two of my favorite episodes, followed by “This Side of Paradise”, “City on the Edge of Forever”, “Balance of Terror”, “Trouble with Tribbles” and “The Naked Time” with the little alien dog

Thank you so very much for your time, talent and contribution to this TV franchise that so many million of people have enjoyed as pleasant entertainment. Especially I thank you for your extra dedication and devotion to your fans by replying as often as you have on this Blog considering you are much, much older than many of us and I pray you are still in good health and spirits to read and have these “fan” letters repay you in some small way for the gift you have given all of us in this Star Trek pleasure “trip”

Bless you,

Sincerely,

Tim Fremuth

I have just discovered your website/blog and started making my way through it, delighting in the long list of entries that promises a wonderful reading experience. Star Trek was a huge part of my formative years and beyond — I’ve never stopped watching it — and I even have it to thank for bringing together me and my best friend in life from the age of 14 until today, 52 years later ! I’ve also been an old film fanatic since the age of 13, and anything having to do with behind the scenes adventures is something I never get tired of reading about.

“This Side of Paradise” is (like for so many others) a particular favorite episode for me, where all the elements merged so wonderfully to produce one of the most emotionally satisfying examples of what episodic tv COULD do. Your sensitive direction in particular I believe is responsible for much of that. To realize that this was your first ST episode is to see how remarkable your skills were in seamlessly picking up the characters and their relationships, interpreting with the actors DC Fontana’s beautiful script and collaborating with Jerry Finnerman to produce one of the most gorgeously shot episodes. I don’t think there’s ever been a lovelier actress than Jill Ireland to grace the show (and I’m well aware there were tons of beautiful actresses across 3 years) but her scenes were really something special.

This blog entry was so great — thank you for recording your career memories which I’m so looking forward to immerse myself in, and I’m happy I was able to express my appreciation for your efforts while you’re still here!

Warm regards,

Karen Snow

Welcome to my trek Karen. And I’m more than happy when you write “and I’m happy I was able to express my appreciation for your efforts while you’re still here!”