Filmed December 1965

It was early December when I drove out to Warner Bros. Studio and entered the gate on Barham Boulevard for the first time. Warner Bros. was the only lot of Hollywood’s seven major studios where I had not yet worked. As I drove through the studio, I passed a sound stage and thought James Cagney’s YANKEE DOODLE DANDY might have danced there, another one where Joan Crawford’s MILDRED PIERCE might have had her chain of successful restaurants, and one where Bogie might have uttered the immortal line, “Play it again, Sam” and then the many soundstages where Bette Davis’ decade-long procession of brilliant screen characters, unmatched before or since, were possibly filmed. The soundstages where Paul Muni brought Emile Zola, Louis Pasteur and Juarez to life and those where Busby Berkeley reinvented the movie musical with 42nd STREET, FOOTLIGHT PARADE and all those GOLD DIGGERS. What I did not realize as I drove past those soundstages was that in the next twenty-two years I would work more on that lot than any other studio in Hollywood. The show I was reporting to was THE FBI, Quinn Martin’s new production in association with Warner Bros. But reporting for this new series was not as daunting as it had been in the past. I had already directed nine productions for Quinn Martin in the previous seventeen months and producing THE FBI was Charles Larson, formerly associate producer on 12 O’CLOCK HIGH. The staff included director of photography Billy Spencer, art director Richard Haman, production manager Howard Alston and casting director John Conwell. I had been associated with all of them on 12 O’CLOCK HIGH. The assistant director was Dick Gallegly, new to QM Productions, but I had previously worked with Dick when he was second assistant director on DR. KILDARE. And THE FBI was a return for me to crime shows, a genre I had enjoyed directing on NAKED CITY and ARREST AND TRIAL.

Some things in life we learn the hard way. I always stood next to the camera during filming, sometimes on the right side, sometimes on the left. During the setup when Earl fired the gun …

… I was standing camera right in the position of the man he was shooting. I was directly in the line of fire and as the gun blasted, I felt stings on my face from the pellets of the blank that was fired. Needless to say I never again stood in the line of fire of a gun when filming.

Heading the cast for the series was Efrem Zimbalist Jr. as Lewis Erskine supported by Philip Abbott as his superior and Stephen Brooks as his partner. I had worked with Stephen three years earlier when he had a recurring role on THE NURSES. THE FBI was another crime show, but a crime show with a difference. NAKED CITY and ARREST AND TRIAL had been cop shows; this one was about the Federal Bureau of Investigation, its stories drawn from the files at the Bureau. The part of the story devoted to the criminal, usually the predominant part of most crime series, in this case had to relinquish more of its time to those seeking to catch the wrongdoers. THE FBI was taking a back seat to no one.

I remember that when I started directing film, I truly believed that I would never forget any actor with whom I worked. Big aspiration? No. Impossible to accomplish? You bet. Just the sheer number of performers that a television director worked with made that an impossibility. In 1974 when I was prepping an episode of THE WALTONS, I went on the set one day of the show currently filming and watched Victor French performing as guest star. Victor had recently had a huge success with his own series. When the scene was finished, he came off the set, saw me and came over and greeted me effusively. He reminded me of the SUSPENSE THEATRE we had worked on together a decade before. I had forgotten that we had even met. And on THE FBI that remembering problem was exacerbated by the number of actors cast as agents in each show, many of them in small roles. I had not viewed SPECIAL DELIVERY for several years. As I prepared the clips for this posting I recognized the actor playing Agent Leeds. It was Sid Conrad. Twenty years later Sid Conrad played young Kirby’s father in my stage production of YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU. After that he appeared in an episode of THE PAPER CHASE that I directed. And we interacted socially. And all that time I did not realize we had worked together twenty years before. Now I wonder if Sid remembered. If he did, he never mentioned it.

For the role of Linda Rodriguez, a very good Hispanic woman’s role, we immediately cast beautiful Barbara Luna as the companion of the fleeing bank robber. For Bobby Porter we took a little more time. The western series RAWHIDE had recently ended its run on CBS midway through its eighth season. That meant series’ star Clint Eastwood might be available. Stars of recently cancelled popular television series were very sought after for guest appearances, so John Conwell contacted Clint’s agent to check his availability. As I remember, he was available but the agency was having trouble locating him. After a couple of days when they had had no luck, we decided we had better move on and we selected Earl Holliman, another graduate of the Pasadena Playhouse, but in a class a few years after mine. Earl was one of that army of established film stars in the fifties with booming careers who saw feature film work dry up. Television in the sixties offered them not only a place to continue to act, it provided them opportunities to play roles they had been denied in features.

I think there were more new sets per episode on THE FBI than any other series I ever directed. The permanent sets were the FBI offices. They were very imposing but usually were not used for many scenes in the stories. It was my good fortune to be associated again with Richard Haman, art director for the series and whose work on 12 O’CLOCK HIGH I had so admired. He always provided more than just a room in which to place the actors. Notice the flashing Grace Hotel neon sign outside the window of the seedy hotel room.

And then there was William Spencer, in my opinion one of the unsung artists of Hollywood film. Billy won an Emmy the year before for his black and white photography on 12 O’CLOCK HIGH. THE FBI was the first time Billy worked in color and he hated it. He told me that he switched off the color when he watched color films on his color television set at home. He watched them in black and white. But Billy was just as great an artist in color as he had been in black and white. He lit for color just as he had done in black and white, using cross lighting and artistically treating each frame of film as a portrait to be painted with lights.

Scott was played by William Bramley. He had played Officer Krupke in both the Broadway and film version of WEST SIDE STORY. This was the fourth time in two years that I cast him in one of my productions. He had been in THE BULL ROARER on BREAKING POINT and two episodes of SUSPENSE THEATRE, A HERO FOR OUR TIME and THE JACK IS HIGH. And he would be appearing in more of my productions in the future.

Night for night filming during the winter months had its advantages and disadvantages. Because sunset came so early, night filming began earlier. Thus work could be concluded sooner. On the downside I can attest to the fact that filming at night in December or January in southern California, whether on the backlot or some location, could be a bone chilling experience. Many was the time the grip crew would provide a fire in a large can around which those not actively involved could gather for a moment of thawing out.

I had done minimal exterior night filming up until this time and most of that had been on studio backlots. Quinn Martin insisted on night scenes being filmed at night rather than the more economical day for night process. The stories being told on THE FBI (and actually on most of Quinn’s series) were very film noirish, which meant that they occurred at night. Again Billy Spencer has to be commended. My staging for the night scenes in SPECIAL DELIVERY covered a very wide expanse and he still managed to do more than just photograph it. Again he painted with his lights.

As I’ve written before, roles for women in television were becoming scarce and good roles were very rare. Although a woman was seldom the main protagonist in THE FBI stories, the wives, girlfriends or accomplices still managed to provide better roles for ladies than were being offered on many other shows.

I have my schedules for this production, but I didn’t save the daily call sheets. I vaguely recall that inclement weather affected our work at the next location. The wind blowing during the sequence between Erskine and the boy with the kite indicated a possible rainstorm coming. And I’m remembering that it did start to rain as we finished at that site and moved to the next where we manage to complete another sequence, and that Claudia Bryar, in another one of her early appearances in one of my productions, had to return the following day to film the final sequence of the day, her scene with Rhodes. In my next lifetime I know I will keep daily logs so that I will be more efficiently prepared for a possible website.

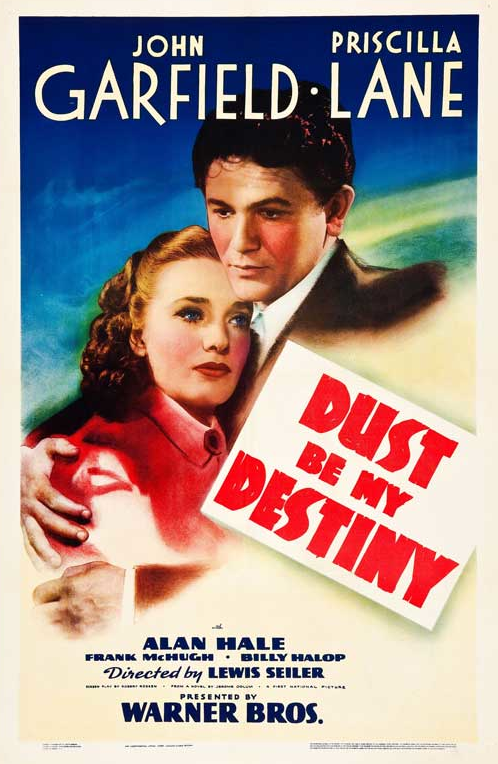

I favored the crime films produced by Warner Bros. in the thirties and forties. There was an energy and grittiness in their telling, a feeling of stories fresh out of the headlines of the daily newspapers. And Cagney, Bogie, Edward G. Robinson — Hollywood didn’t turn out any guys tougher and meaner than that trio. In 1938 they were joined by a fresh face from Broadway, John Garfield, who brought a different quality to the screen criminal. He was tough, but sensitive; circumstances seemed to turn him into a perpetual victim. One of my favorite Garfield films was DUST BE MY DESTINY in which he and Priscilla Lane were on the lam.

When doing a story dealing with a hardened criminal, I always wanted to resist compromising and softening his character in order to gain audience sympathy. Cagney I thought was the best when it came to refusing to compromise, as witness his sensational performance in WHITE HEAT. If in the end you couldn’t feel sympathy for his Cody Jarrett, you certainly were fascinated by him. But Garfield was softer, more vulnerable. His characters couldn’t always cope with their circumstances and ended up being the victim. Victimizing the criminal provided a way of gaining sympathy for him.

From the location where we filmed the sequence of Erskine and the boy with the kite, we moved down the road to the site we had selected to film our final sequence. It had started to rain, as is evident by the wet roads and the muddy field, but it let up enough that we were able to finish the sequence before we had to wrap for the day.

And so I ended my first case at THE FBI. I soon learned I would be returning for a second case and later that the following season I would be devoting my full services to THE FBI.

The journey continues

Tense and exciting episode. The police car sliding in the dirt was slippery due to the rain, but it really was effective. Earl Holliman was fine and so was Barbara Luna. I felt more sympathy for her than him. I don’t think you got Clint Eastwood because he was probably on his way to Italy to make those Sergeo Leone Westerns that made him an international star! I rather doubt that he was hiding from you! Looking forward to another post real soon,Ralph!

Hi, Mr. Senensky! Just wanted to say my father would only watch two television series, “The Untouchables” and “The F.B.I.” This series was among my earliest childhood memories and as a youngster of two, I thought Erskine’s convertible was a special F.B.I. car because it had no hood. I love this series for the great acting, great score, and great direction. Thank you.