FILMED October 1969

The THOLIAN WEB firing took place in August, 1968. I did not work again until four months later in December when I directed my first THE COURTSHIP OF EDDIE’S FATHER. I continued to work during the following ten months (suddenly I was employable again) but I only directed half-hour comedies (four more of COURTSHIP and four of THE BILL COSBY SHOW). There were three half-hour dramas that I directed for INSIGHT (a series I’m hoping to discuss soon) but since I contributed my services to that show, that hardly addressed the situation of my no longer being hired to direct television dramas. Could it be that the whole town regarded me as did David Victor, for whom I had directed several episodes of DR. KILDARE? When my name was submitted to him to direct on MARCUS WELBY, David said, “But he’s a sit-com director.” And then in October the ice was broken. I was booked to direct an episode of a new series at MGM.

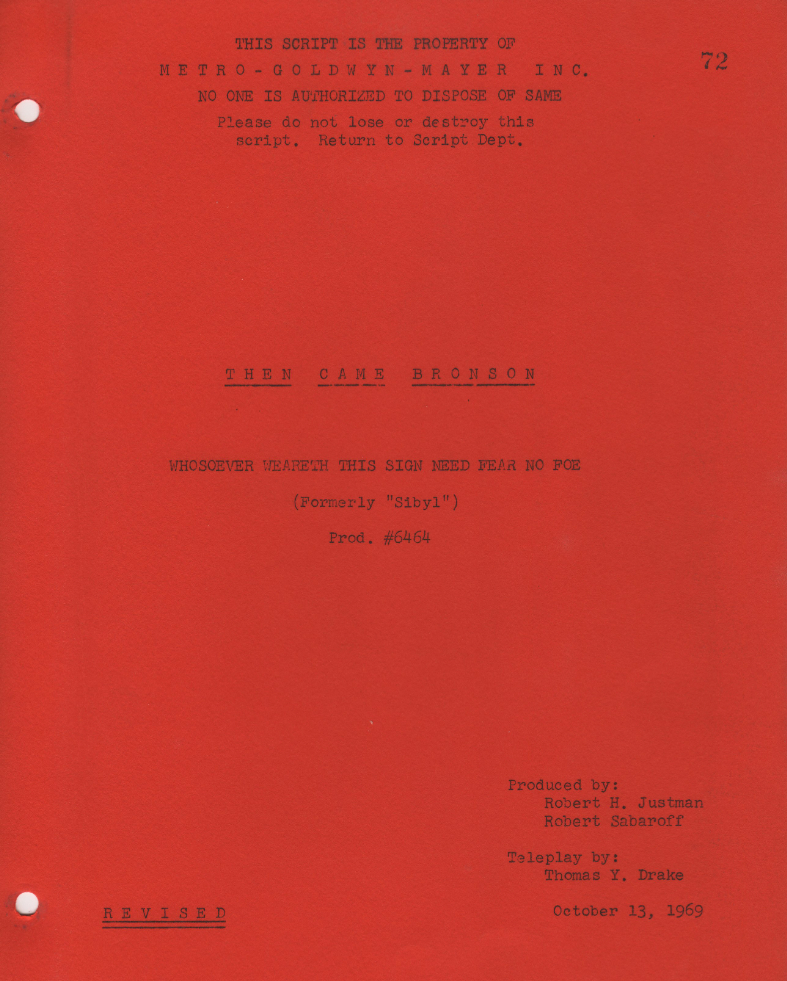

It was THEN CAME BRONSON, being co-produced by Robert Justman, former associate producer on STAR TREK. The script was WHOSOVER WEARETH THIS SIGN NEED FEAR NO FOE, formerly titled SIBYL.

THEN CAME BRONSON, written by Denne Bart Petitclerc, had been filmed by MGM as a two-hour television pilot for NBC. It aired in March, 1969, was a big success and NBC scheduled it as a one-hour series to begin its network run in September of that year. The show was sometimes accused of being a knock-off of the movie EASY RIDER, but it actually preceded the release of that movie. If it was a knock-off, I wondered if the inspiration came instead from ROUTE 66. Like the two protagonists of that earlier road show Bronson was a young man traveling around the country seeking the experiences life has to offer. He traveled alone, and instead of a Corvette his mode of transportation was a motorcycle. Like ROUTE 66 the series was shot entirely on location, so I flew to Phoenix, Arizona, where my episode was to be based. Once there I was told we were going to film two days in Sedona, which was 116 miles north of Phoenix. Since motoring to Sedona would have been a two-hour drive, we flew up there in a small plane to scout our locations. Normally I had no fear of flying, but my friend Jerry Finnerman had very recently been scouting locations in Colorado, and the small plane in which he was traveling crashed. The pilot and Robert Sparr, his director, were killed; Jerry was the only passenger to survive.

I have not been back to Sedona in forty-three years, so what I write now is what I recall from that far distant past. As our small plane flew into the area, the scenery was breathtakingly beautiful. With its red-rock monoliths, Sedona is often called “Red Rock Country”. I remember the landing strip for their airport as being rather unusual. It was atop a mesa; it is in fact called Airport Mesa, and I remember it feeling like we were landing on a navy aircraft carrier, except over the edge the drop-off was not to water and it was several hundred feet down. We found our locations for our upcoming shoot and then faced the ordeal of getting back into the plane for our return flight. Since it was a small plane I hoped it would get up enough speed so that by the time we reached the end of the mesa, there would be sufficient power to have us going up into the air rather than the other direction. My hopes were fulfilled, and we safely returned to Phoenix. A few days later after arranging for the locations in Phoenix it came time for the company to move to Sedona for our first two days of filming. I was very graciously offered the convenience of being flown to Sedona, but I declined. The two-hour drive appealed to me more than the thought of again landing on that mesa.

I met Michael Parks six years earlier in 1963 when he auditioned for THE BULL ROARER on BREAKING POINT. I tell of that meeting in full detail in my post of that show. I don’t know if Michael remembered that meeting; the subject never came up. On-camera he was totally professional; his persona was a mirror of his behavior in life. Off-camera he was coolly aloof, like David Janssen. Or maybe he did remember.

I don’t remember if I interviewed Renne Jarrett in Hollywood or if I cast her without meeting her, but we connected immediately. I remember when we were filming the sequence near her bus, while they were setting up for the shot down by the water, she and I were gabbing away when I happen to notice Michael, about fifteen or twenty feet away holding a headset of earphones. Renne and Michael both had wireless microphones attached to their costumes to record the scenes when we filmed, and during the set-up time I had laid my headset of earphones, which I wore during filming so I could hear the dialogue, on the ground. Michael was holding my earphone to his ear, listening to our conversation.

I thought that ROUTE 66 was a masterwork template for producing a series on the road. Their itinerary was laid out; arrangements were made at the different cities that would serve as the bases of operation for the productions; and then many times the author went to the city (in my two instances Corpus Christi and Galveston) where the story was developed to make use of the surrounding environment. But I don’t think that was they way they did it on THEN CAME BRONSON. I think they bought a story idea from a writer, commissioned the script to be written and then filmed it wherever they happened to be in their itinerary. It was a risky way to do it. I certainly lucked out. Sedona was close enough to Phoenix to film a third of our show there. For our location in Phoenix the script called for a “mystery castle,” and the location manager took me to the Gulley Mystery Castle. As I remember, they did not know of the Gulley house when they selected Phoenix as the place to film this show, but it was perfect for our needs, so perfect and with such a rich history I would have liked to film the story of the Gulley family and their castle rather than the script I was assigned.

In the 1930’s Boyce Gulley discovered he had tuberculosis. Not wanting to drag his wife and three year old daughter through the agony of what he perceived as his future and choosing not to live a life of quiet desperation awaiting the end, he ran away from home. He left his wife and daughter in Seattle and moved to Phoenix. In his loneliness he remembered the times he and little Mary Lou built sand castles on the beach in Seattle, and how she would cry when the tide washed them away. He remembered her saying, “Please, Daddy, build me a big and strong castle that I can live in.” And so with the little money that he had, he picked up a mining claim of some 80 acres in the foothills of South Mountain, just outside the city, and spent the next sixteen years building a castle by hand while waiting to die of the disease he had been diagnosed with. He used naturally found material in the area and old abandoned artifacts found in various scavenging trips to the Southwest and Mexico. With never a letter or contact home, he lived out his life in his strange and beautiful creation until 1945 when he was thrown by a horse into a cactus bush. He died soon after, not from tuberculosis but from complications caused by the fall. The house was left to his eighteen-year old daughter, who came to Phoenix with her mother and took up residence in the castle her father had promised to build for her. By the time we arrived a quarter of a century later, her mother had died, but Mary Lou still resided in the castle. She was around during our filming, but I had little opportunity to interact with her, but as I said, I regretted that it was not her story I was filming.

I had seen the National company of BOYS IN THE BAND when it played at the Huntington Hartford theatre in Hollywood. Michael Lipton played Harold, the role that Leonard Frey had portrayed so brilliantly in the off-Broadway production and in the film, and Michael was equally as dazzling. I asked for him for the role of Hermes, and I had my request filled without any objections.

I had eighteen rooms, thirteen fireplaces and several patios from which to select areas in which to stage the different sequences, and each area was amazing in the versatility and originality of its design. Gulley was truly a man ahead of his time. I remember in the kitchen he had concocted a hood, which was suspended over the burners on the stove. That was long before that became standard design in American kitchens. There was a glass wall partition created with the square glass lids of containers, and small clocks and other artifacts were embedded in walls made of rock and stone he had gathered from the desert and from riverbeds. Even his most prized possession, his Stutz Bearcat automobile, contributed its wire-rim wheels to the structure.

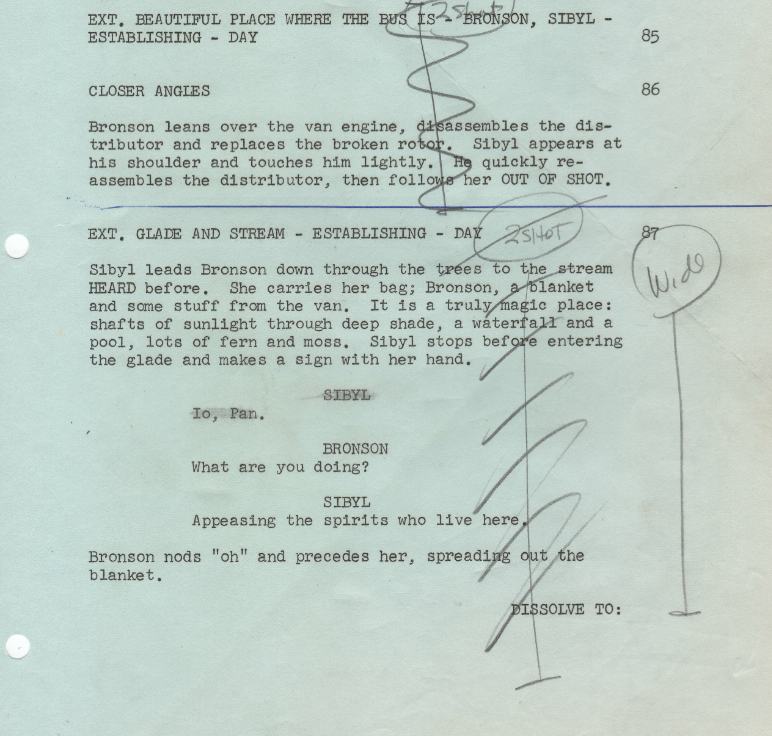

Sibyl’s line when she hung the medallion around Bronson’s neck, “Whosoever weareth this sign need fear no foe,” was obviously the inspiration for the change in title of the episode from its original title of SIBYL. I wondered it that too might have been inspired by ROUTE 66, noted for titles like that (i.e. NARCISSUS ON AN OLD RED FIRE ENGINE). But sometime between completion of photography and the night the show aired, someone made a counter change, and the show reverted to its original title, SIBYL.

I’m ambivalent when it comes to the occult, to ghosts and séances. When I was very young I had a Ouija board. In the late 1950’s I directed a production of William Archibald’s THE INNOCENTS (the stage adaptation of Henry James’ THE TURN OF A SCREW) at the Morgan Theatre in Santa Monica. The story involved two young children, Miles and Flora, and their involvement with ghosts. One Friday night after rehearsal the cast and I decided to hold a séance on the small darkened stage of the theatre. We did, but we were unsuccessful in raising anything except a little dust. When directing a play I used to rehearse during the day on the weekends. Since at the Morgan Theatre the weekend was the time for the volunteer members of the theatre to work on the stage building the set, our rehearsal was held in the theatre’s large lobby. At one point when I was working on a scene with two of the adult actors, the young ones playing Miles and Flora decided to have their own private séance and found some quiet dark area of the theatre not in use and proceeded to have one. Suddenly the two of them came rushing back into the lobby, disturbed and frightened. They couldn’t explain what it was that frightened them, but they had obviously raised more than dust. I later related this to Mel Wixson, one of the founders of the theatre group. Mel was not surprised. He told me that during the week, when volunteers would come in the evenings and work building the set in the shop, he was not available because he worked a swing shift. So he would come during the day and work on instructions left by the night crew. Many times he said he would have to leave. He would hear a heavy breathing and feel a presence near him. Geoffrey Morgan, the former mayor of Santa Monica, who had been an avid supporter of the theatre and had been instrumental in their acquiring the property on which the theatre was built, had died of a lung disease. Later when we were in performance, Audrey Descher, mother of Sandy Descher who was playing Flora, would stay backstage during performance, helping with the two kids and actually functioning like an assistant stage manager. There were six actors in the play. Audrey told me with that small cast she always knew where everyone was. And she added, she also felt there was another presence. She heard heavy breathing.

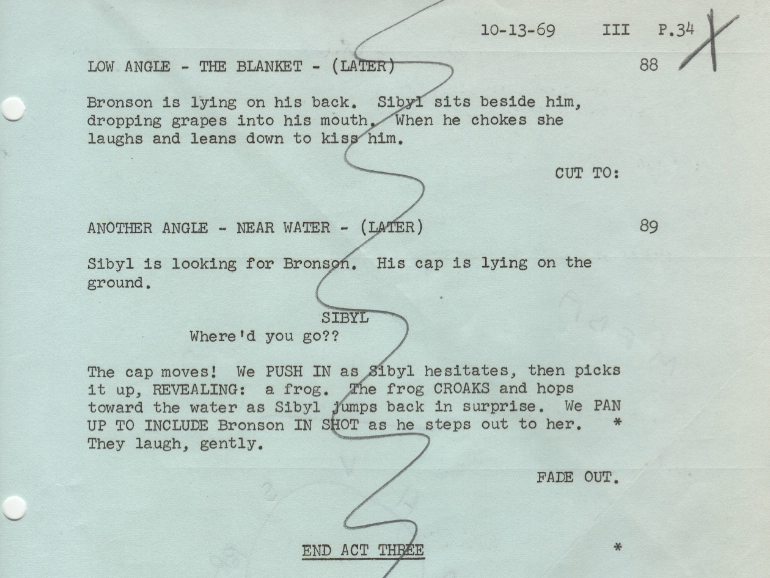

In the script that was not the end of Act Three.

I had never been involved in a professional séance, so I did not feel confident about directing the big séance scene in the film. I asked the producers to hire an expert in that field to act as technical advisor. Why they turned that assignment over to the casting director, I will never understand. Anyway one was contracted and sent him to Phoenix. A driver from our transportation department picked him up at the airport and reported that our technical advisor had been escorted off the airplane under guard. When our “expert” had boarded the plane in Los Angeles, he had announced some cockamamie story about his current mission (I have forgotten the ridiculous details of his yarn) and had immediately been suspected of being a terrorist. Somehow by the end of the flight that situation had been cleared up, and he was (unfortunately) released so that he could come fulfill his commitment with us. The cast and I assembled that evening so he could give us a presentation of what we would be doing. Emerging in a tacky toga-like garment, he delivered what seemed like a bad comedy act on the occult. By the time he was finished, I realized I would have to rely on my own shaky instincts to stage the scene.

When we returned to Phoenix after our first two days of filming in Sedona, we still had a half-day of exterior location work – the final scene of the film, which was shot on our third day of filming on a highway near the outskirts of the city.

THEN CAME BRONSON was developed at MGM when Herb Solow was Executive in charge of Production. Solow had held the same position at Paramount earlier when under his stewardship STAR TREK and MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE were created. All three were unusual concepts for television. Unfortunately THEN CAME BRONSON did not duplicate the success of its predecessors. It debuted with high ratings, based on the success of the pilot film, which had aired six months before, and its future looked very bright. At least two of the episodes for the season had aired by the time I began filming. One day when I was working in one of the castle’s patios, Michael was visiting with Paul Stanley, a director who had filmed an episode and was set to direct another one following me. As I passed by them, intent on setting up my next set-up, I heard Michael proudly raving about the high ratings those early show had garnered, and he felt the success of the show was directly attributable only to himself and producer Robert Sabaroff, who was in charge of the scripts. But the ratings soon drifted downward, and the show was cancelled at the end of the season. Unlike STAR TREK, which had also been cancelled at the end of its first season, there was no viewer write-in campaign to reverse the cancellation. Did THEN CAME BRONSON deserve this early death? True it was not a show dealing in standard plots. Its aim seemed to have been to make people think, rather than excite them with aggressive action. But since it was more of an esoteric show aimed at a smaller audience, might that audience have grown if the show had been allowed to continue, had been allowed to improve, to rectify its flaws and develop its inherent strengths. Maybe the scripts needed some adjusting and the character of Bronson would have grown with time. Who knows, that might even have helped raise the standard of television programming. I know I’m being an impractical dreamer, and of course it didn’t happen. The network did what it usually did — it threw the baby out with the bath water. THEN CAME BRONSON joined that distinguished list in the television graveyard of one-season victims of the television ratings game.

The Journey Continues

Ralph – wonderful to see Amzie Strickland again – Amzie could do anything, she was amazing – surely she must have been one of television’s most prolific character actors. Thanks to you, I had the privilege of meeting her – a genuinely warm human being – when my dad passed away from Parkinson’s he had the 8×10 she had given him still hanging on the wall of his bedroom. I can’t believe she is gone now.

I’m sure you must miss her.

How many times did you two work together?

– John

As best as I remember, counting a play we did together — 8!

I guess Michael Parks really did believe what he said. In his archive interview executive Herbert Solow said the series came to an end when Parks said he no longer wanted to do it. And since Parks was the only star there really wasn’t anything that could be done about it.

Thanks for this blog Ralph. I love hearing first person accounts about “then came Bronson” There is a lot more history to the show and the many reasons for it’s demise than can be discussed in a short Email/blog. But the show still has a large following, and a small group of us gather every year to commemorate the series. More info on past gatherings and more insight and behind the scenes info here at http://www.jimbronson.com/

Fascinating. I did not know about your blog for Bronson. The amazing thing I am finding out by response to my website is how many shows from that long ago time have a responsive audience today. My big regret and because of it I almost did not do a post on SIBYL was the poor faded quality of my copy of the show. It does not do justice to the red mesas of Sedona. Billy, do you have a better copy of SIBYL? If you do, I will gladly and eagerly pay to purchase a copy of it.

I loved Then Came Bronson. I watched every episode. Your analysis that “I wondered if the inspiration came instead from ROUTE 66” was echoed in a Mad Magazine satire of it. In their intro they said, if memory serves me “Bronson had half as many wheels as Route 66 and was half as good” I thought that phrase was clever and funny, but I still loved Then Came Bronson.

As I watched the 2nd video unfold, I was thinking how this was the feared nightmare of many parents back in the day: their young daughter in hippy-ish garb with a VW bus(!) is stranded alone in the middle of nowhere and is met by an unknown man on a motorcycle.

I see your point about lack of “aggressive action” in the plot. When I first saw Michael Lipton as the creep, I assumed he would either kidnap, assault, or brainwash Sibyl – then Bronson rides to the rescue. But, she was never in any danger. How can Hermes scare anyone when he invites a minister to his castle?!

The best part of this post is the 8th video – ALL of it. There’s the transition from the pyramid eye decal on the bike to Renne Jarrett looking through the pyramid formed by the bike’s chassis. There’s the amazingly compliant cat. There’s Jarrett snuggling up to Michael Parks. There’s Red Rock Country. There’s Parks singing. There’s more Jarrett! It concludes with a pullback view that looks like God’s Country. Except for the 4:3 aspect ratio, this clip would have fit in well to any cinematic feature film.

After about 30 seconds of the 4th video, it hit me – this music is Richard Shores! He did similar instrumentation on ‘The Wild Wild West’ the year before.

Regarding the wireless microphones used in the 3rd video, I didn’t know that technology existed back then. Was it a recent invention for the industry, or had you used them before? Was this option available when you did the fishing scene with Milner and Begley in ‘Route 66’?

Phil, I don’t remember when we started using wireless microphones. But if they were available as early as 1963 when I filmed the fishing sequence with Milner and Begley, we would not have been able to use them. The small radio box attached by a wire to the microphone was stuck in the actor’s pocket and would have been inundated by those cold, cold waves.

Stephen Bowie’s recent write-ups about ‘TCB’:

The actor in the station wagon in video one is Stu Klitsner:

http://classictvhistory.wordpress.com/2014/11/05/then-came-klitsner/

Complete article:

http://www.avclub.com/article/hang-there-then-came-bronson-captured-spirit-count-211297

I started watching this show from the beginning a couple of months back, and this is one of the better episodes so far. Loved how you shot Sybil and Jim’s conversation by the river (trippy), and the way you framed people in outdoor scenes in general — it added something dynamic to what was too often a stagnant, talky series. Even the oddball mysticism stuff is underplayed. Nicely done.

Ralph,

Since this series was totally filmed on location did you film on a Saturday? In researching various projects I’ve noticed many location shoots film on Saturdays but not on Sundays. Is that due to budgetary reasons?

Steve

Hi Steve: I don’t know (and didn’t know at the time) why, but location filming was a 6-day week, Monday through Saturday and off Sunday.