Filmed March 1963

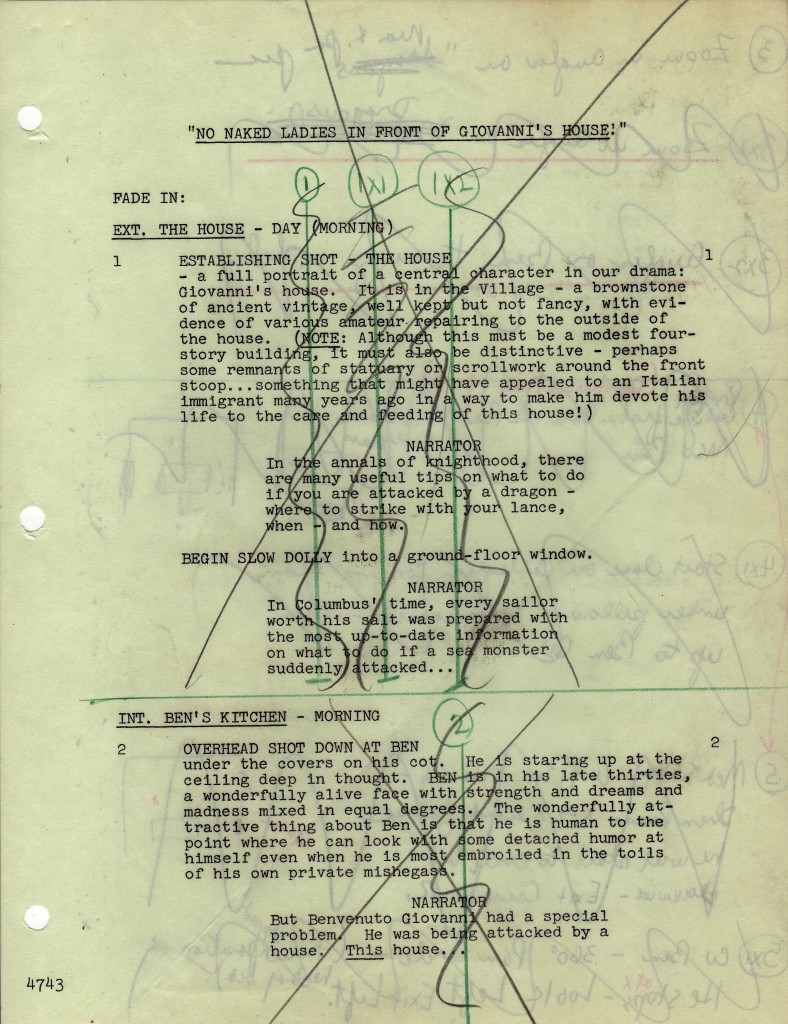

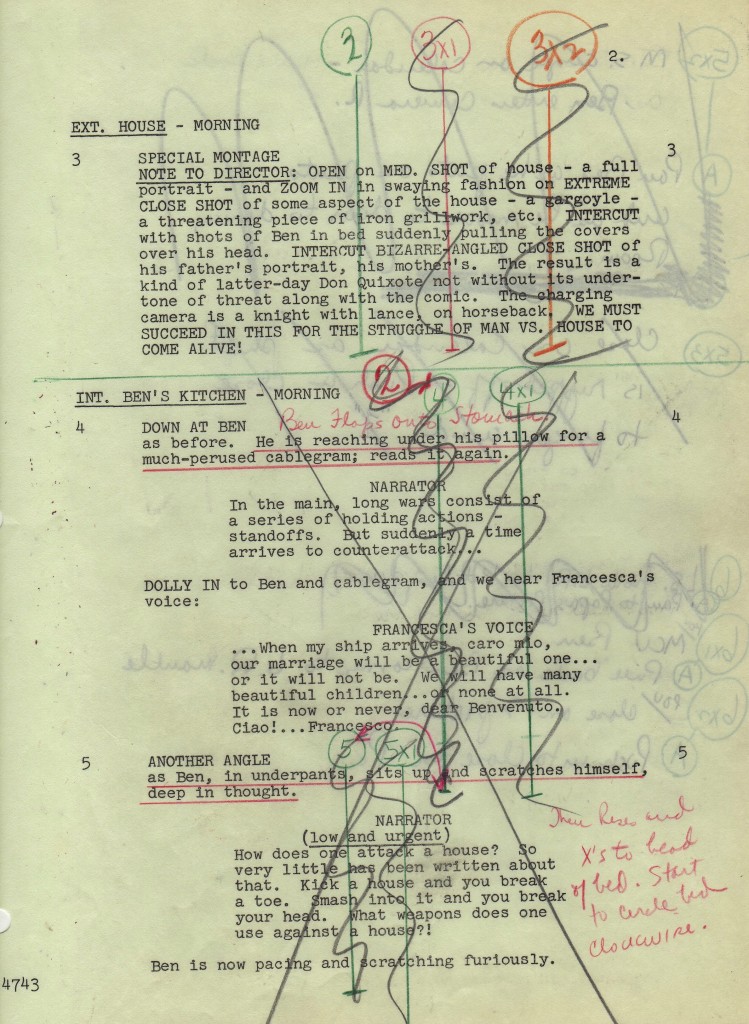

After wrapping ALIVE AND STILL A SECOND LIEUTENANT I flew back to the west coast, where I had just a couple of days to unpack, do laundry, pick up my next script (a COMPLETE one again), repack and fly back to New York to start work on my third production for Herbert Leonard, another NAKED CITY titled NO NAKED LADIES IN FRONT OF GIOVANNI’S HOUSE. I arrived the morning of Saint Patrick’s Day, checked into my hotel, and the production people picked me up early to scout locations before the day’s big Parade. There was only one major location to find, Benvenuto’s house; but why don’t I let the author’s script describe what we needed.

The location manager had a list of potential houses to show me, and after the turmoil of the search for the isolated house in Corpus Christi for ROUTE 66, it was a relief to find what we needed fairly quickly. As I was being driven back to my hotel, I asked where the company was shooting that day. I was told they were in midtown Manhattan. I decided I would be dropped off at the location, say hello to the crew and then walk back to the hotel. Little did I realize what I was letting myself in for. The company was shooting at a construction site, a new building going up. And when I say up, I mean UP! Sixty-two stories up. And they were filming at the top on the sixty-second floor. But having committed myself, there was no backing out. They dropped me off at the site, and I was escorted over to the outside elevator that was going to take me up to where the company was filming. I am being generous when I call what I got into an elevator. I swear it seemed like a piece of flooring attached to four tall vertical poles at the corners with horizontal bars about waist high to discourage (but not prevent) anyone thinking of jumping off on the ascent. As we went up, it did not seem as if we were rising; rather that the surrounding skyscrapers were dropping, so that we were looking down on them. That ride stopped at around the fifty-second floor. The final ten flights had to be walked. The stairs for those last ten flights hadn’t been completed yet. The structural framing for the risers was in place, but the treads had not yet been built, so loose planks of wood were laid across the openings. I finally reached the top, totally open, with a nice cold breeze, no, a not-so-nice cold wind blowing. I greeted everyone — Paul Burke, the crew, stunt man Max Klevin and then found a box dead center where I could sit and watch. Paul Burke was at one end of the building, leaning over to see what was going on down on the street below. I feared at any moment the wind blowing would give him the chance to see it close up. They were filming a fight scene; Max and another stunt man had safety ropes attached to their waists as they struggled at the very edge of the building. I was already wondering if there might be the possibility of my sitting there until they finished construction, so I wouldn’t have to get back into that damned elevator. And then they called lunch, and everyone started leaving. Well I wasn’t about to stay up there alone. Besides I was tired (I had traveled all night) and hungry. So I started down those improvised stairs to the fifty-second floor, where I had a decision to make. It was not a difficult decision. I WALKED down the remaining fifty-two flights, staggered back to my hotel, giving thanks all the way that I had not been assigned the script I had just visited.

NO NAKED LADIES IN FRONT OF GIOVANNI’S HOUSE, as the title might suggest, was a comedy–my first film comedy (this was fourteen months before MAYBE LOVE WILL SAVE MY APARTMENT HOUSE on DR. KILDARE). On ROUTE 66 when we didn’t have a completed script, had difficult locations and inclement weather, we started filming anyway. Here I had a completed script, a show that was going to film mostly in the studio, and my few locations all selected. I was raring to go, but I sat around for several days waiting for the current show to finish shooting. Finally even difficult shows eventually wrap.

I was pleased to learn Harry Guardino had been cast to play Benvenuto Giovanni. This was a reunion for us; the previous September we had worked together on DR. KILDARE (HASTINGS’ FAREWELL). As with the casting of Robert Sterling in my first NAKED CITY (ALIVE AND STILL A SECOND LIEUTENANT) and Don Dubbins on ROUTE 66 (IN THE CLOSING OF A TRUNK), I welcomed the chance to direct again an actor with whom I had previously worked. It was an advantage for me to have a knowledge of how the actor worked, but just as importantly there was a trust that the actor had in me, which made the communication between us deeper and more meaningful.

The casting of the tenants by Marion Dougherty was terrific. Casting for a Broadway play and even for most feature films could entail endless auditions. Episodic television didn’t have time for that. My usual procedure in casting on the west coast was to start by going through the Academy Players’ Directory, a three inch thick annual publication containing the names, portraits and agency representation of every actor willing to fork over the fee it took to be placed in the book. I would prepare a list of possibilities for each role, which I would take to a meeting with my casting director, who had also prepared his or her list. Most of the roles could be cast without having the people come in. I knew performers I had worked with; I also knew performers whose work I had seen and admired. But that was on the west coast. New York had a whole community of fine actors with whom I was not acquainted. That was why it was so advantageous to have Marion. She knew actors and had a wonderful eye for matching the actor to the role both in appearance and in ability.

I think the influence of live television from the Golden Age of Television of the fifties was still being felt. This script by Abram S. Ginnes could have been produced on any of the New York hour-long live television programs of that era. I appreciated the comedic quality of the writing when I filmed it; I appreciate it even more today when I compare it to the comedy being heaved at us from our screens — large and small.

As before, filming exteriors in New York city was an exciting experience. There was a visual energy that not only provided an exciting background to the action, there was another energy that seemed to permeate the actors because of working in those surroundings and seemed to add an extra coating of reality to their efforts.

The challenge of this script was to reconcile its broad farcical events with the usual gritty realism of the series. But then, isn’t that the challenge of all good comedy? When I was on staff of PLAYHOUSE 90, they did a production of James Thurber’s THE MALE ANIMAL. PLAYHOUSE 90 aired on Thursday night. Friday mornings across the country newspapers would carry reviews, people at water coolers would discuss and critique the previous evening’s airing as if it had been a Broadway opening. The response to THE MALE ANIMAL was not good. The reviews were almost totally negative. It was the alternating show, so I had not worked on it. Lenny Horn, the assistant director on the production, was in the office the next morning, totally surprised and confused by the response to the show. He told me he had thought they had a fine production, a very funny show. He asked me what I thought of it. I said I didn’t think it was very good. He wanted to know why I thought that. I said, “Because it wasn’t real.” His response: “But it’s a comedy.” Get my point?

Columbia Studio in the thirties was known as “Poverty Row.” Although it was considered one of the seven major Hollywood Studios, under tyrannical studio head Harry Cohn it operated on a far less opulent level than its six competitors. Unlike those competitors it did not have a long list of major stars under contract. When it came time to cast one of their few major A productions, the studio had to negotiate for the services of free lance stars or try to borrow stars from one of the other studios. A legendary story from that era concerned Clark Gable, who in 1934 (not yet the superstar he was to become) asked his boss at MGM, Louis B. Mayer, for a raise in salary. As punishment to the young upstart for his ridiculous request Mayer made a deal, and Gable was loaned to Columbia Studio, where they were having difficulty casting their latest Frank Capra production. Gable was so furious, legend has it, that he reported to the studio drunk. But things did work out. The movie was IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT, the surprise smash hit of the year, and Gable won the Academy Award for his performance. He returned to MGM a bigger star with more ammunition behind his request for an increase in salary.

Although Harry Cohn was long gone, the frugality of his reign lingered on. An example: the script called for a holding cage where Benvenuto would be retained. MGM would have built a separate set. In their small studio in lower Manhattan there wasn’t room for another set so, for this episode only, a caged area was added to the standing police squad room set.

Now in the usual procedure for editing a film the editor puts together his first assemblage from the yards and yards (sometimes it seems like miles and miles) of film that has been shot. This then is screened in a screening room for the producer, who will give the editor his requests for changes and cuts. (The director’s cut in the early days of television did not exist.) The editor makes the requested changes, and the film is again screened for the producer. Any further changes the producer may ask for, plus the matter of editing the film to the specified length required by the network are made. Then the film is shipped off to the other departments — sound effects, music, possible special effects — before it is sent to negative cutting. But Bert Leonard didn’t do it that way.

During the few days I was back in Hollywood after finishing filming NO NAKED LADIES and before leaving for Texas for another ROUTE 66, I went to the studio one afternoon. That afternoon turned into a late night event. Bert took me with him to a large editing room where he had not one but three (maybe four) editors at work. Each editor had a reel of the picture that he was cutting. The room buzzed with the sound of the several moviolas. When an editor completed assembling his reel (about ten minutes of film) Bert looked at it, not in a screening room but right there in the editing room on the moviola. He had his hand on the moviola’s brake, so that if he saw a place where he wanted a change made, he stopped the film and gave the editor his instructions, which the editor made note of. When he had viewed the entire reel, the editor went to work on the requested changes, while Bert moved to another editor, another moviola. When Bert was satisfied with a reedited reel, he said, “Ship it.” That’s the way he worked his way through the six reels. Never did he look at the film from beginning to end. Never did he view it on a big screen in a screening room. Never was the matter of the length of time discussed.

As I remember we were there in the editing room till after midnight. Strangely of all the sequences in the film, I remember Bert editing the scene of Francesca at the street market the most strongly. I don’t remember whether we shot the scene at a real street market or whether we had to create our own market in the street, but I do remember being very impressed and encouraged by the care Bert took to make each moment in the scene work, of admiring his fearless intercutting of closeups for reactions with never a thought or care to “speed it up.”

In Hollywood’s heyday large cathedral interiors were created on studio soundstages. But television did not have the money, and New York’s NAKED CITY did not have the studio space to continue this procedure. Live locations were the answer and a very effective, economical one at that. The cathedral for Benvenuto’s wedding was the first of many in which I would film.

One of my standing rules was that when working in drama, look for the comedy, and when working in comedy look for the drama.

In HASTINGS’ FAREWELL Harry Guardino had one word of dialogue to learn. In NO NAKED LADIES he had considerably more, in fact a great deal more. But that was another major difference between telvision then and television now. Television then was not afraid to let actors explode in dialogue rather than have them running away from exploding buildings and cars.

The final scene in Benvenuto’s house was in his basement. Somebody got the bright idea that if you needed the basement of a New York house for a set, why not use the real basement of a real New York house. So I was shown the basement of the building which housed the studios for NAKED CITY. It was great. Atmospheric. Sinister. But then some wiser heads prevailed. In the sequence we were to film, Benvenuto starts a fire in the basement. Even with the greatest precautions this posed a dire risk. There was one narrow stairway out of the basement. If a stray spark were to cause a major fire, there would have been 7 cast members, a minimum of 3 camera folk, me and the first assistant director, the sound boom man (the mixer could have been upstairs), at least 2 special effects men to tend to the fire in the scene, at least 2 grips and 2 gaffers and the script supervisor all rushing for that lone stairway. That’s a grand total of 20 people. As I said, some wiser heads prevailed, and it was decided to create a basement set in the upstairs studio.

There were two sequences in our script that took place at the docks; the first when Francesca arrived on the ship and the final one with the ship sailing away. Well obviously we couldn’t schedule two trips to the docks; that would have been too expensive. So I filmed the second sequence the same day as the first; but all film angles had to exclude a departing ship. We found out what date the ship would be leaving, and on that day a second unit (just an arriflex camera, no sound) was sent with Harry and Marisa to film two shots involving the departing ship. By the time the film editors put it all together, you would never have known it was not all filmed on the same day.

During the few days I was back in Hollywood after finishing filming NO NAKED LADIES, when I went to the studio the day I ended up in the editing room til the wee hours of the morning, as I rushed through the dark dilapidated halls of Columbia Studio, I bumped into Peter Kortner. My first year on PLAYHOUSE 90 when I was still a secretary, my desk was near Peter’s office. Peter, the son of German film star, Fritz Kortner, was a story editor on PLAYHOUSE 90. He was obviously at Columbia on a development deal. We greeted each other, and he asked me what I was doing there. I told him I was directing episodes of ROUTE 66 and NAKED CITY. His response: “Well I’m surprised. I’m really surprised.” I don’t know where Peter went after that. I continued down to Herbert Leonard’s office, on my way to Texas to direct another ROUTE 66.

The journey continues

hello ralph

i could only watch 5 of the videos you sent with this show, 6 had the quicktime player icon.

mike

It appeared in this episode Horace McMahon, the captain, has limited speaking roles. In fact, in the one clip, he walked out of the office and then turned and walked back in without saying anything. Had he taken some time off?

One question about this episode. In the scene where police are stomping on the trap door Detective Arcaro is yelling “it’s the police.” One of the times he yelled this it seems he threw in a slight Italian accent.

I know sometimes an actor or director will like to throw in little stuff like that. Or did I imagine this?

Thanks again for the memories.

Horace probably had less to do in this episode than in some,but it was not because of his taking time off.There was also a phone call scene between him and Arcaro that I have not included in the clips. And no, that wasn’t your imagination about Arcaro’s Italian. In the opening scene where Paul Burke and Harry Bellaver came to the apartment house and Harry was trying to quiet the crowd, one of the women says excitedly, “Oh, Italiano!”

In the last clip I wish I could have been the beautiful Marisa Pavan. Harry Guardino was a sexy and versatile actor! It was obvious you enjoyed working with him. The script was funny and touching about the “agonies” of growing up and accepting responsibility. It was a great “change of pace” to the usual heavy dramas on NAKED CITY. It seemed that everyone involved was having fun. Superb directing with a remarkable cast, Ralph!

Hello Mr Senensky – I just saw this episode for the first time last night on Youtube…wonderful balance of comedy and drama. You guided Harry Guardino through a pitch-perfect performance. Really enjoy all the articles on your site – thank you for taking the time to share them with us.