Two years elapsed between my productions of THE GLASS MENAGERIE and NIGHT MUST FALL. To capsulize those years: I responded positively to Martha Barclay’s suggestion (bordering on urging) to continue my theatre education at Northwestern University. In June of 1949 I enrolled at the University, attended the summer session and then the fall quarter. Then through a combination of my father’s health and a set of circumstances September of 1950 found me installed as the resident director for Mason City Little Theatre’s 1950-51 Season. In the ensuing 10 months I would direct 4 productions plus 2 Childrens’ Theatre productions. I would pick the plays, subject to the board’s approval. I had not engineered this change in plans, but I was ready. Enough of going to class! I was 26 years old. It was time to start doing, and a laboratory had emerged in which to do it.

I had been an admirer of Emlyn Williams’ 1935 play NIGHT MUST FALL ever since I saw the 1937 MGM film version starring Robert Montgomery. I don’t remember why I missed seeing it when it played in Mason City; in those days I didn’t miss too many films, but somehow I missed that one, so a couple of weeks later on a day I had spent in Clear Lake (my aunt and uncle rented a cottage there for the summer), that evening my cousin Arlene (age 14) and I traipsed to the Lake Theatre to see NIGHT MUST FALL. To this day Arlene and I laugh over our reaction to that movie and what ensued, but we weren’t laughing then. When we exited the theatre, not unaffected by the thriller we had just witnessed, we realized there had been a very strong summer storm. As we made our way back to the cottage over dark unlit water-drenched streets, we encountered a crew from PG&E repairing a downed electric line. I remember seeing a live wire lying in the middle of the road. Someone on the crew steered us around the live wire and cautioned us to be extra careful as we continued on our way. The streetlights of course were out because of the downed lines, which made the trip back to the cottage even scarier than the thriller we had just seen.

I selected NIGHT MUST FALL as the third of the four plays I would be directing that season. It presented directing challenges I had not yet faced. The plotting was dark and suspenseful; the relationships were intense, and the interactions of the three principal characters would need to reflect the evil shroud of sensuality that hovered over the English bungalow in which the story transpired. Since it was only my fifth directed production after graduating from the Pasadena Playhouse, I was still a very inexperienced director.

I don’t remember how, when or where I met Millie Chorak. I just remember she was a local lady and a very talented artist. She became a close friend and my art director. I would design the floor plans (the placement of archways, windows, doors and the arrangement of furniture), and Millie would design the wall décor and paint the flats. That was an enormous challenge for her. Productions were presented on the stage of the Mason City High School. Mason City Little Theatre did not have its own theatre building with a scene dock where sets could be constructed and painted. My father’s jewelry store had a large space at its rear that he very generously offered, but the area was not spacious enough for us to construct flats and set pieces. We could only do the painting there. The area was not spacious enough for us to paint the flats in an upright position as would be done in a scene dock. With the flats for the set lined up along the two walls, there was just room enough, one at a time, to lay a flat on stands in the open area, and that’s where Millie painted. Now Millie didn’t just paint the walls a flat color. She designed “wall paper”, then with an airbrush and the stencils she designed, she sprayed the pattern onto the flats, which she had previously painted the base color. For NIGHT MUST FALL I wanted the walls to be painted in cool blue tones. Here is our set for NIGHT MUST FALL, but in black and white.

Casting for two of the three principal characters was easy. I wanted the aforementioned Martha Barclay to play Mrs. Bramson, the fifty-five year old wheelchair-bound invalid who divided her time between her chocolates and being abusive to her household staff and her niece, who worked for her. I knew Steve Stahl from before. He was the brother of D.L. Stahl, who had played Tom in THE GLASS MENAGERIE, and it was Steve’s portrait in World War I uniform that hung on the wall of that set and lit up every time Amanda referred to the husband who had deserted her and the immense charm he possessed. Steve owned a print shop located in the building and under the local newspaper, the Mason City Globe Gazette. He was not trained as an actor like Barclay. It was strictly an avocation, but I sensed in that very quiet sensitive man the depth for Danny, the baby-face monstrous bellboy from the Tallboy Inn. For Mrs. Bramson’s introspective niece, Olivia, I cast someone I didn’t know before, Jean Pearce, but that casting did present a problem. Jean, even wearing flats, was a shade taller than Steve. I solved that with my staging; I never had them standing next to each other. When they were in near proximity, by having Steve a bit downstage of Jean, he seemed taller, …

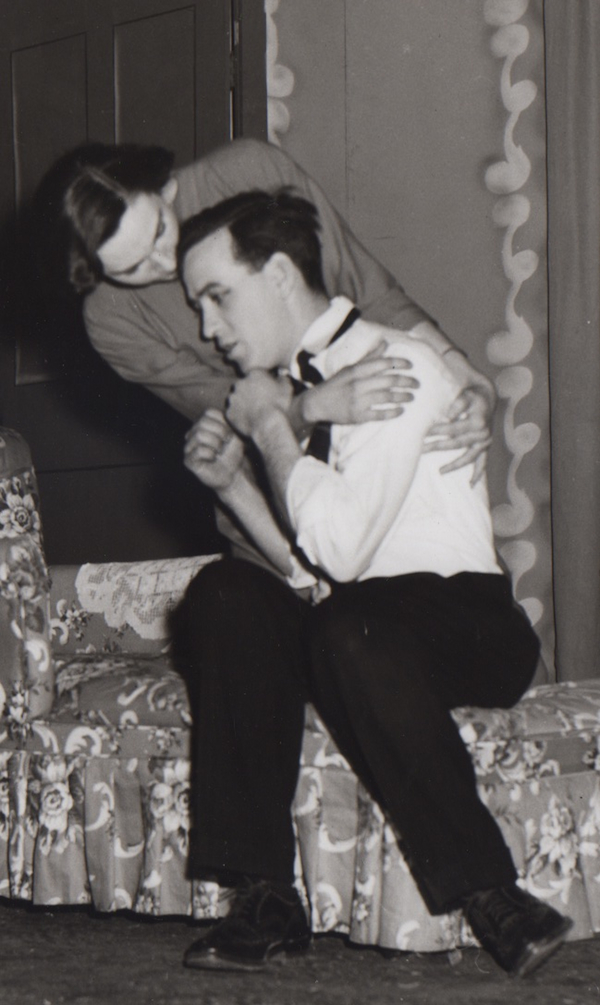

At one time when I was serving as her assistant, Myrtle Oulman told me, “If at any time the action on the stage could be frozen, the audience should be able to tell what was happening from the picture presented.” The developing relationship between Olivia and Danny was a major thread in this story. Their related positions on stage needed to show that, progressing from Olivia’s early suspicions through her growing sensual feelings.

Incidentally, those are not posed photos. Frank Free, a local photographer, came to our final dress rehearsal, and they are candid shots during that performance.

I realized something very early in my directing career. I insisted that from the start of rehearsals, all of the actors would wear the shoes they would be wearing in performance. If a lady’s character was going to be wearing high heels, I did not want her rehearsing in flats. Since Martha Barclay would be seated in her wheelchair for most of the performance, I wanted that wheelchair available from the first rehearsal, and I learned something from Barclay. If a character spoke to her necessitating her turning to him or her, she didn’t just turn her body. Turning the wheels of the chair, she rotated the wheelchair. She used the wheelchair as part of her body.

NIGHT MUST FALL was remade as a film in 1964 with Albert Finney playing Danny. Times had changed. Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 PSYCHO had extended (brilliantly) the extent to what was deemed necessary to shock and thrill an audience, and he accomplished that in spite of ingeniously casting Anthony Perkins, until then seen only in young All-American-boy roles, as Norman Bates. Finney’s Danny was no longer disarmingly innocent. Bosley Crowther in his New York Times review stated of the NMF remake, “…it falls short of the psychotic outburst of Mr. Montgomery 27 years ago.” Imagine what a revival on stage or screen today, awash in violence and blood, would probably be. I still prefer the understated stirring of an audience’s imagination.

One of the most frightening things in the play was a mere prop. A murder had been committed at the Tallboy, and a lady was missing. When Danny was brought to the cottage because of his sexual involvement with Mrs. Bramson’s maid, Olivia sensed immediately there was something disturbing behind his boyish charm. When he was hired by Mrs. Bramson to be her constant companion, Olivia found herself with mixed feelings – she was also attracted to him. When the missing lady’s body was found, her head was missing. Headed by Olivia, the group brought his luggage onstage, including that prop — a not so innocent looking hatbox!

It worked then. I think it would be effective today, but I wonder if it were being filmed today, would the filmmaker resist the urge to open the hatbox!

I have just finished viewing a group of current films before voting for the Directors Guild of America award. I wonder how Mrs. Bramson’s murder would be done today. Sixty-five years ago Olivia and the servants all left. Mrs. Bramson was alone in the cottage. When she called out and no one came, she calmly rose from her wheelchair and walked to the table to get a chocolate. Then as she became aware that she was alone in the house, she began to panic. She became hysterical …

… and collapsed in total terror on a chaise.

Danny comforted her and helped her back to her wheelchair. Exhausted she looked up to see him standing before her.

She said, “What are you going to do with that cushion?

… as the lights slowly faded and the curtain descended.

I repeat: I wonder how Mrs. Bramson’s murder would be done today.

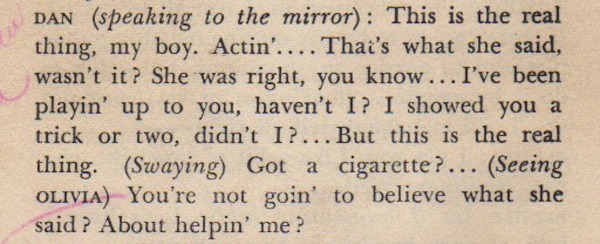

For the finale Olivia returned to the cottage with the police, who arrested Danny for Mrs. Bramson’s murder. Danny in handcuffs stopped in front of a mirror where he spoke to his image.

Frank Free, the photographer, had been unable during the dress rehearsal to get a shot of that action with Danny’s reflection in the mirror, so I asked for a posed still publicity shot. His face in the mirror was not lit, so I had Steve with a cigarette in his mouth light a match. Mission Accomplished.

I think we did something right.

I found directing to be a never-ending learning experience: Probably most important was how to work with actors. In Community Theatre actors came with varying degrees of talent, different amounts of experience, and as a group they included an infinite range of personalities. I could not have a “set” way to steer an actor into a performance. I found I must make it personal, adjust my guidance to his or her talent, experience, personality.

I learned very early that in critiquing, never start with the negative. Always start with what the performer is doing well and build on that with a suggestion of what to do in place of what I felt needed changing. And I always gave criticisms quietly and confidentially. No one but the actor I was speaking to heard what I said. I did not want everyone in the room to know what the performer had done wrong, what they were going to try to do to correct that. I did not want the actor to feel that everyone in the room was sitting in judgment.

That’s just a tiny bit of what I learned, and not so strangely a dozen years later when I was plying my craft on Hollywood soundstages, I still did it the same way.

Ralph,

Your quiet, confidential private approach to directing actors on THE WALTONS has remained with me through the years – it has been the single-most primary foundation of my approach as a producer to not only actors, but every other member of the production team including the crew.

I agree! Especially “The Pony Cart” – it is a masterpiece of understated perfection, possibly the best-directed episode of ANY television drama.