FILMED August 1967

There was a published theatre book when I graduated from the Pasadena Playhouse written by Frenchman Georges Polti: THE THIRTY-SIX DRAMATIC SITUATIONS. The book listed his thirty-six situations and contained extended explanations and examples of every one that might occur in a story or performance. I never owned the book, but I’m sure I read it. Whether I believed what Mr. Polti prescribed was a moot point. At that early point in my career I was like a sponge, soaking up all of the information I could absorb, but delaying any processing and eliminations. By the time I started directing television thirteen years later, I was still not a total believer in his restricted list, but I did admit that there were wisps of possibility in his categorizing.

I apologize for the faded quality of the video clips. Although it looks like we were filming sepia, we were filming in Technicolor. My main concern is that the performers and performances are very vivid.

How many viewers of this website recognize which plot of my previous films THE MONEY FARM seems to be cloning? Here’s a hint: it was made four years earlier in 1963. Give up? It was MY NAME IS MARTIN BURNHAM, an episode of ARREST AND TRIAL. In that story Martin Burnham had an argument atop a tall building under construction with a friend and coworker. When the person he argued with fell to his death, Martin was charged with murder. And no, I didn’t cast James Whitmore, who had played Martin Burnham, to play John Patrick McKenna in this film as an act of typecasting. John Patrick McKenna’s character was the diametrical opposite of Martin Burnham. It was a vibrantly written role, and I admired and respected Whitmore’s talent as an actor and sought out any chance to work with him.

In the editing a major trim was made in the ending of the previous scene …

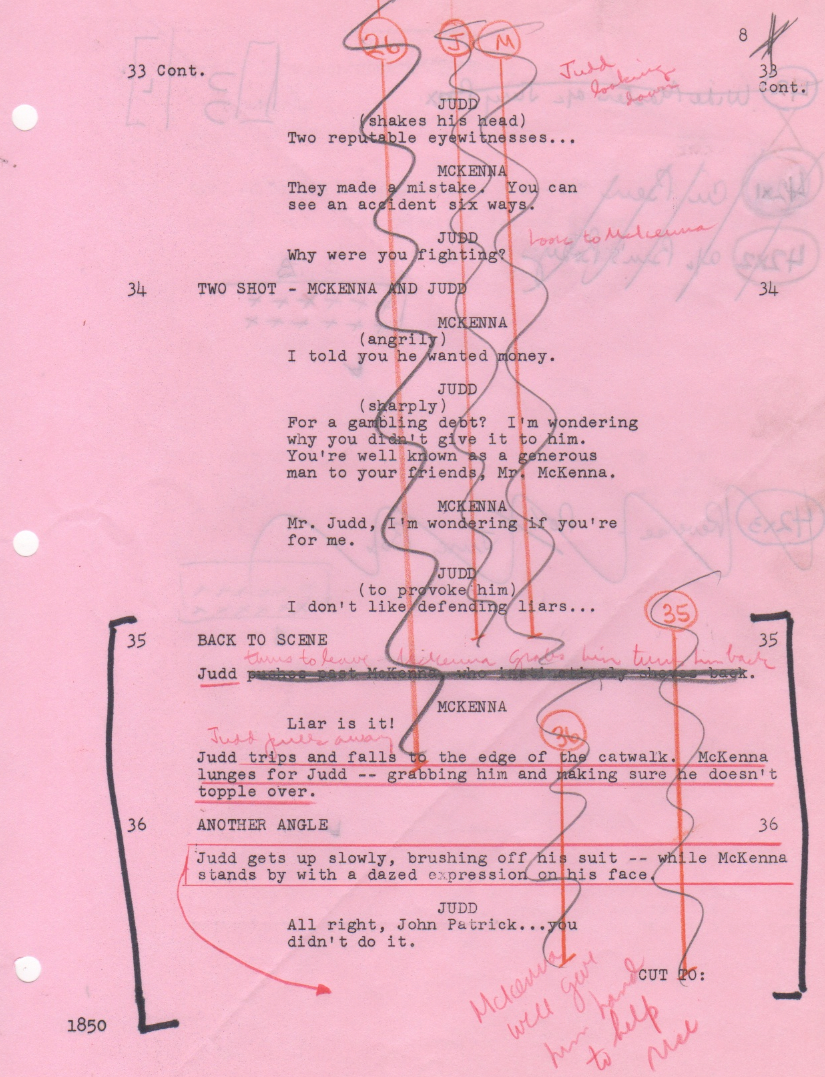

You’ll notice Scenes 35 and 36 showing Judd’s tripping and being saved from falling off the catwalk by McKenna were cut. The scene in the film ends with McKenna’s speech, “And I’m wondering whether you’re the right man for me, Mr. Judd,” rewritten by Whitmore to replace, “Mr. Judd, I’m wondering if you’re for me.” (You may also notice that Whitmore reworded most of his speeches to fit the Irish brogue he used.) I learned a valuable lesson. How much more dramatic it was to retain the adversary relationship between Judd and McKenna!

Our six-day shooting schedule began with our one day of location filming at the visually impressive oil refinery in El Segundo, a beach town south of Los Angeles Airport. The city earned its name because it was the second Standard Oil refinery on the West Coast. El Segundo, from Spanish, means The Second in English.

The script for THE MONEY FARM (and it was not titled that during production; the original script was titled THE WHEELER DEALER) ran 66 pages. As I reported on my last post, THE SNOW JOB, that script ran 64 pages, and since the anticipated running time for the first assemblage was over 60 minutes, a one and a half page scene that was filmed was not even a part of the first assemblage. The unusual thing on THE MONEY FARM was that the first assemblage, for a script that was even longer, was short. An additional scene had to be written. That scene was the lunch scene with Judd and Ben. Since by the time that happened I was long gone, and since I do not have that scene in my director’s script, and I don’t remember directing the scene (although I must admit, it is as I would have directed it) the additional scene was obviously directed by someone else, probably the director of the production currently before the camera. That was not unusual. It was a carry-over of the procedures long used by the major studios. Are you aware that Victor Fleming, who in 1939 won an Oscar for directing GONE WITH THE WIND, was not the only director on that film – that George Cukor, Sam Wood, and David O. Selznick all directed scenes for the film. Are you aware that Victor Fleming, who that same year received sole directing credit for THE WIZARD OF OZ, was not the only director on that film – that George Cukor, Mervyn LeRoy, King Vidor and Norman Taurog directed scenes for the film. That was a situation that eventually was changed. As the Directors’ Bill of Rights evolved, the original director of a film had to be notified and hired to direct any additional scenes added to a project. If he was involved in another production and not available, only then could another director be assigned.

Forty-three year old Martha Hyer (Leora) had been part of the Hollywood scene for 21 years. Nine year earlier in 1958 she received an Academy Award nomination for her supporting role in SOME CAME RUNNING, in which she starred opposite Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Shirley MacLaine. Director of Photography John Nickolaus (this was the first of several projects we did together) told me that Miss Hyer had come to him with a request and instructions for how she would like to be photographed: in her close-ups she specified where she wanted to look –she did not want her look to be too close to the camera, and she did not want to be photographed in extremely large close-ups. This was a first for me.

Amzie Strickland (Barney’s wife) was one of my closest personal friends. We met in 1955 at Barney’s Beanery on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. We had both arrived in Los Angeles the previous year, and she joined Paul and Claudia Bryar and me for lunch. The Bryars and I were in rehearsal for a production of MY THREE ANGELS at the nearby Players Rings Theatre, and Amzie had just auditioned for the role of Rosemary in their production of PICNIC. Amzie got the role. I remember when I saw the production being disappointed in her performance. I felt it was too overt, too melodramatic, but because of her performance in the role she secured the services of one of Hollywood’s top small agencies (Meyer Mishkin) and her long career in Hollywood took off. I got to know more about Amzie. She and Claudia Bryar were close friends from their days growing up together in Oklahoma. From Oklahoma she had gone first to Chicago and then to New York, where she had a very successful career as an actress in radio. The thing I remember most, and of which I am most proud of Amzie, is how successful she was when she came to Hollywood and had to adapt her radio approach to acting to the visual demands of film and television.

That was my first production with Diana Muldaur. I had seen her in a John Houseman stage production at UCLA, and like my reaction the previous year when I had found William Windom in a similar way, I was eager to cast her in one of my productions. This was the beginning of a short but lucrative association. I cast Diana again in my next assignment, an episode of I SPY, and the following year I cast her in RETURN TO TOMORROW, an episode of STAR TREK, the first of the two that we did together on the series that refused to die.

Courtrooms made for exciting drama: TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, THE CAINE MUTINY, WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION, JUDGMENT AT NUREMBERG, ANATOMY OF A MURDER. Television in its earlier years, when dramas based on words rather than action were still allowed, had some good ones. Although I filmed many scenes in courtrooms, I only directed two series where a lawyer was the leading protagonist: ARREST AND TRIAL (and here attorney Chuck Connors only had half the show) and JUDD FOR THE DEFENSE. I liked the courtroom because it was theatre. I learned when I was doing ARREST AND TRIAL that lawyers didn’t just stand still and ask questions. They moved about like actors do on a stage. I learned a favorite position for them was to stand by the jurors, so that when the person testifying looked at him, he (or she) was looking at the jurors. And I liked that courtroom dramas usually had fine roles for actors.

I would like to blast an old Hollywood myth. The accusation was that Hollywood actors really weren’t actors. Their scenes were done in short pieces that were then joined together to create a performance. James Whitmore and Martha Hyer did not have to have that protection. They were two solid pros, they came to the set prepared, and boy, did they deliver!.

THE MONEY FARM was my sixth association with 20th Century Fox Studio, but it was the first time I worked on their main lot on West Pico Boulevard. My first four 20th Century Fox productions were on 12 O’CLOCK HIGH, a co-production with Quinn Martin Productions, which I filmed on the old Fox lost at Western- and Sunset Boulevard.. I then directed an episode of THE LONG HOT SUMMER, a 20th Century Fox production, but it was filmed on the MGM lot in Culver City.

This was the only time I worked with Carl Betz. Carl is mostly remembered for the eight years he spent as Donna Reed’s husband on the ABC sitcom, THE DONNA REED SHOW. He won an Emmy for his performance as Clinton Judd, but JUDD FOR THE DEFENSE only aired for two seasons. He was a very versatile, attractive, powerful actor, whose career was cut short with his untimely death in 1978.

The thing I admired about James Whitmore was that when playing an unsavory, flawed character, he didn’t compromise. Like James Cagney (remember his Cody Jarrett in WHITE HEAT, his final, “Made it Ma! Top of the world!” atop a gas tank about to explode) he didn’t soften in order to gain audience sympathy. And like Cagney, his characterizations always ended up with viewers rooting for them.

My website is a journal, a memoir of my Hollywood trek. It is not a platform for political discourse. But I can’t resist. THE MONEY FARM was produced in 1967, 47 years ago. I am surprised viewing it today that network television allowed this frank presentation of the underbelly of the oil industry. I am dismayed that 47 years later, I don’t think anything has changed.

Very enjoyable episode Ralph – and a great script. And another superb performance from James Whitmore – I never thought about it until you mentioned it but Mr Whitmore and James Cagney certainly are comparable; especially in terms of the intensity they brought to their performances.

I didn’t watch Judd for the Defense during its first run, but I remember Carl Betz receiving very favorable reviews – now I know why. If he had not passed so young, I wonder if he might have had a career similar to Brian Cranston; i.e., someone known primarily for their light comedy and SITCOM work, who startles everyone with their dramatic ability and talent. I agree with you, he brings strength and power to his character.

Plus another one of my favorite character actors – Allan Oppenheimer – not sure there’s enough digits to count all the shows he has been on – and he’s still going strong today doing voice work.

Hi Mr. Senensky,

Thanks for another interesting account of your fascinating directorial career. I have seen many episodes of Judd for the Defense and I think this is one of the best because as you mention it, James Whitmore’s unwillingness to compromise when playing an unsympathetic character and yet he still managed to make you root for him because of his charisma. It’s a very modern performance. I think he should have been Emmy nominated for this role.

I know that Judd has a good critical reputation, but overall I must confess that I found the series to be underwhelming. Few of the scripts lacked the moral ambiguity of “The Money Farm,” many times I was dismayed that the eps would cop out at the end by having the villains/unsympathetic characters having a change of heart at the last second, and some of the more controversial/new issues such as alcoholism, rape, and mental challenges were clunkily handled.

I didn’t realize that Martha Hyer had certain demands about how to be photographed. Well, I guess she knew what she was doing because she looked gorgeous as always.

On another note, I think this is one of her better roles as she tended to get typecast in either icy or waify parts. Here, she is able to play a sympathetic wife without being sappy. May she rest in peace.

Like so many, no like most of the Hollywood actresses of that era, when it came to how she was photographed, she knew exactly what she was doing. Her face at the jaw line was a little puffy, so shooting her straight on only worked in wider shots (i.e. in her scene with Carl Betz with the coffee pot). Her hair was also styled to help cover that. She was most attractive in the closer angles with her look further from the camera, where again her hair was styled perfectly.

When I worked in Ft Worth (2003-4) Martha lived close-by, I nearly ran over her one day when she dashed across the road from behind another car. This is how we met. I apologized, she laughed, taking the blame, we lunched, and I got to know her for a brief time as a neighbor. What a lovely lady. I’m sorry to see she has recently passed.

A joy to see Amzie again. I was surprised to see her recently on the old ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW playing Barney Fife’s very first romance, long before “Thelma Lou”.

Ralph, I think we might have discussed this before, however I seem to recall a certain episode of THE WALTONS, I think it was THE PORTRAIT, when you and Earl Hamner had a strong disagreement over a scene. You shot it your way – it was your last day of your show. Director Harry Harris had the following show and had been in prep. The next shooting day of his show he re-shot your scene the way Earl had argued. I recall it being a key scene. There were so many memories, at times I think “did that really happen?” I believe you were never notified, and I thought it strange. Am I correct?

Fun to see Sc 34, the writers calling for a TWO SHOT. I don’t see writers telling a director what to do much anymore, but that old saw of who is the author of the show, the writer or director is still alive and well in good old Hollywood.

I don’t remember ever having a disagreement with Earl. On that show I did have a very strong disagreement with Rod. I wanted some scene rewritten and he wouldn’t do it. I don’t remember anything about a reshot scene. But then that is one WALTON I try to forget. You’ll notice I’ve not done a post on it.

Ah, so it was Rod Peterson, not Earl, makes sense – I think you SHOULD do a post on THE PORTRAIT.

I’ll think on it. It was such a negative experience and as a result in my opinion such a negative non-Walton show!

I always thought of “Judd for the Defense” as the anti-Perry Mason in that Clinton Judd did not always win his cases at the end of the episode.

It was also a reminder that a very young age, I should’ve been asleep instead of watching the show at 10:00 in the evening.

Thanks for posting your experiences on this entertaining, short-lived show.

Judd for the Defense is a very underrated show. I wish it experienced a longer run. I downloaded every episode from YouTube, many years ago.

Unfortunately, time was not too kind to the color prints so, they are way too extreme in some color imbalances.

So, I ran them through a black and white to clean up the contrast and, they look much better. I always though black white heightens the drama in many scenes.

James Whitmore was one of my favorites. You could always count on him to deliver no matter what type of character he was playing.