FILMED February 1967

You hear that driving pulsating beat of the theme song for MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE? That’s the way I remember feeling when I was directing THE TRAIN, the assignment that could almost have been labeled an impossible mission. I have to correct my comment in the Archive of American Television interview that THE TRAIN was filmed in six days. In checking my records I find it was filmed in a scheduled seven days. Whether all MISSION episodes had seven-day schedules or whether the extra day was given to THE TRAIN because of its expansive requirements, I don’t know. What I do know is that seven days was still far from adequate. The series at that time was still being produced by Desilu Studio, so the same leniency in scheduling being given to STAR TREK was probably also in play for MISSION.

The series’ first season was drawing to an end, and the company was in the process of planning changes for its continuance. There had been a problem from the beginning between Steven Hill, the leader of the mission force, and the studio. An action series like MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE always entailed night work and in television night work, because of union turnarounds was usually scheduled for Friday night. For Steven, an orthodox Jew, Friday after sunset was the Sabbath and he refused to work then. So for the current production his character of Briggs had been demoted; he would only receive the instructions for the mission and make the assignments. Martin Landau, a member of the force, would perform the role in the mission that Hill would normally do. William Schallert was cast to perform the role of the doctor that Landau would normally have played.

I did not direct any of the teaser — the sequence of Briggs’ receiving the instructions for the mission and the sequence where he checks the photos to select the force; that was designated on the schedule as stock footage. The only time I worked with Steven Hill was the second day of production when he met with the members of the force. I was concerned that it might be an uncomfortable situation for him, but if it was it didn’t show. I found him to be charming, cooperative and totally professional. And I think he’s a hell of a good actor.

THE TRAIN was a caper film but with a more ingenious plot and more complex characters than will be found in many caper films. Casting was relatively easy. I just went through the list of actors with whom I had already worked and came up with some gems. First William Windom to play Deputy Premier Pavel, the evil heir apparent to power. Eight months earlier when we had worked together Bill had given an amazingly good performance in THE ASSASSIN on THE FBI. For Prime Minister Larya I chose Rhys Williams; this would be the third and unhappily the final time I would get to work with him. Earlier he had appeared for me as the mad scientist in THE NIGHT OF THE DRUID’S BLOOD on THE WILD WILD WEST and as the Communist professor in THE ASSASSIN on THE FBI. Finally there was Noah Keen as General Androv, he too was making his third appearance for me.

Because of the complexity of the Missions and the fact that much of the activity was presented visually without dialogue, there were many, many inserts (close-ups like the ones in the preparation of the x-ray) per episode. Many times these inserts could be omitted during principal photography and completed later as a second unit under the direction of an associate on the production staff. When I was the assistant to the producer on DR. KILDARE that was one of my chores. However I always preferred, when directing, to shoot my own inserts during principal photography.

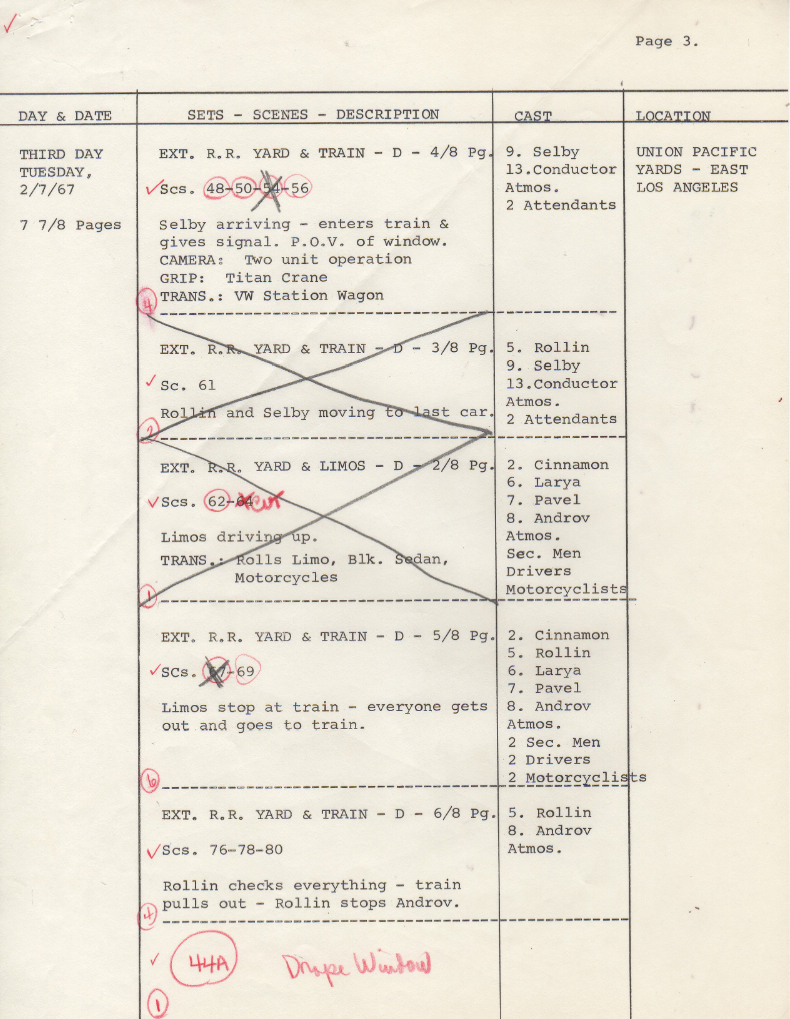

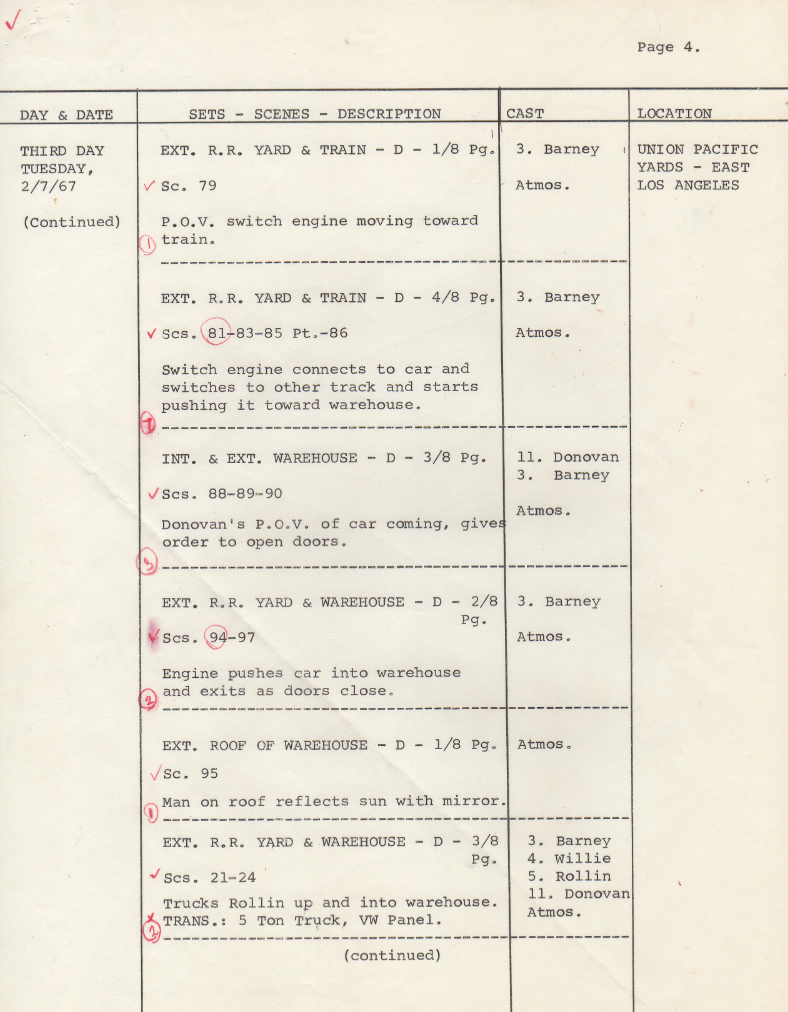

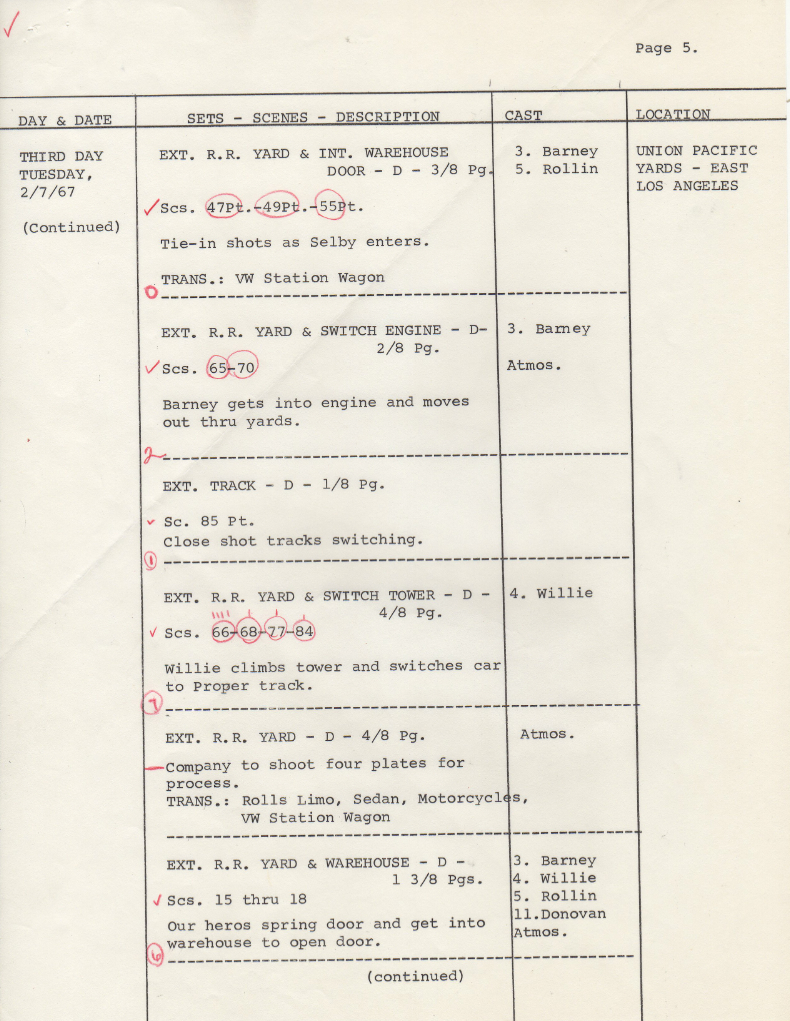

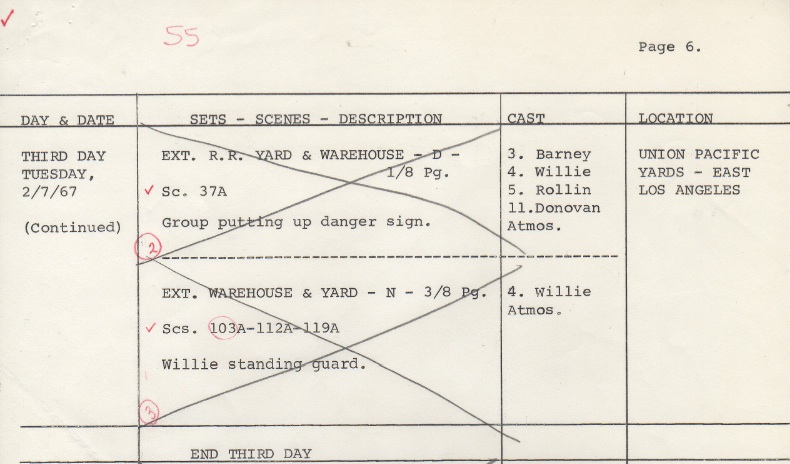

The interior of the warehouse was created back at the Desilu Studio. Within that warehouse set would be the set for the train’s interior. Filmmaking is not unlike a jigsaw puzzle. Each shot is like a piece of a puzzle; put them all together and you have a film. In the case of MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE, most of the pieces were shorter than usual and definitely more plentiful. There was no scene in the film that was three pages long. There were 4 scenes that were at least 2 pages but less than 3 pages long. There were 15 scenes that were at least 1 page but less than 2 pages long. But there were 47 scenes that were less than 1 page long; 20 of those fell on what I considered the crucial day of our schedule: our third day at the Union Pacific yard in east Lost Angeles. Here is our shooting schedule for that day:

I scouted the Union Pacific Yards in East Los Angeles with Barry Crane, the associate producer-production manager for MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE. (He also was a world-class bridge player.) The page count for the train day came to just under eight pages, not an unreasonable amount of work for a day of location filming, but Barry and I both realized the amount of work involved would be impossible to complete. To alleviate the problem a second camera was added and I worked out with Barry that there were some shots that didn’t require sound that could be shot with the second camera when I wasn’t using it. I showed Barry the angle of the shots that I wanted and he oversaw their filming. This was a repetition of what Richard Gallegly and I had done on the production of THE RAID on THE FBI, but here it was something that we preplanned.

Barry oversaw 13 or 14 shots that day. Working in tandem that way the full day’s work was completed and there were 69 setups to be viewed in the following day’s rushes.

This sequence was a challenge. It was like filming a sequence for a silent film, but without the caption cards to help explain the action, which was that the mission of the Mission: Impossible force was to get the prime minister and his entourage on board, disconnect his car from the rest of the train and have the train pull out, have Barney (Greg Morris) connect his engine to the prime minister’s car and switch it to the tracks that will allow him to push the car into the warehouse.

Rhys Williams was plagued with crippling arthritis. He had it when we filmed THE WILD WILD WEST a year earlier, but at that time he was still able to move about quite comfortably with the aid of a cane. When the Prime Minister’s car arrived, I avoided showing him exiting the car. It would have been difficult for him to do; it would have been painful to watch.

Everything I had filmed outside of the warehouse had been absolute reality. My responsibility was to transfer that reality to film. Inside the warehouse was a different situation. Rear projection as seen through the lens of a camera photographing it is very believable, but the human eye looking at a rear projection screen sees a flickering movie screen. The truth of the situation was that Prime Minister Larya, Deputy Premier Pavel and General Androv, in spite of the shaking of the train and the sound effects being furnished by Barney, would not have been deceived for a moment into believing they were traveling through the countryside. My mission was simply to ignore that fact and make the lie believable.

Frankly I thought that bit of business was wrong. I thought the Mission force would have checked so that kind of equipment failure could not have occurred; however our writers, Woodfield and Balter, felt differently. They must have been carried away by the sequence and excited when they viewed the rushes the following day. I can’t say this for sure because I don’t think I ever met them, although they were around the set a lot. But a day or so later I received pages of a new scene they had written. If the sound system breaking down could create an exciting sequence, wouldn’t it be even more exciting to have the film in a rear projector break down with film spewing out all over the place. I guess it might IF there was not a limitation on the running time for the completed film and IF there was not the problem of adding new material to an already overloaded shooting schedule. I pled my case to producer Joe Gantman, a friend from our CBS days, and he agreed with me. The new scene was not added to the already overloaded filming schedule.

In our story the whole sequence from the time the first trucks arrived around 5:00 pm until the train hurtled into the rapid downgrade should have spanned a little over an hour. A feature film with a proper budget would have scheduled the location train sequence for at least three days. But this was television. So Peter Lupus, on guard outside of the warehouse, was photographed not in fading sunlight but in very effective film noirish darkness.

Weeks after filming was completed I went to the answer print screening at CBS and saw one of the agency representatives who was someone I had known earlier in my CBS days. After the screening he asked me how many days we had spent at the train yard and when I said “One,” nobody would believe it.

Since this episode was filmed near the end of their first season, it was only a short time until the Emmy nominations for that year were announced. MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE received a nomination as best television series. When a show for any series was nominated, the producers selected one episode that was submitted to the Television Academy. The Academy then had panels of Television Academy members view the five nominees in each category. Their vote decided the winner. I was told by a member of the production staff that MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE submitted THE TRAIN as their entrant. It won! MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE was awarded the Emmy as the best television series in its first season on the air.

At the beginning of the following television season when directors were booked for assignments for the season, my agents called to tell me there was a request from MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE for me to do six episodes. I turned it down. It was a marvelous show, but it was a killer. Not too long after the following season began, Desilu Studio was purchased by Paramount Studios. The new bosses imposed even more stringent demands on the shooting schedules. I never regretted my decision to say no.

The journey continues

This was my favorite episode! I loved it! It’s amazing it only took 6 days! WOW! It was so exciting–even today! I have never seen Ms Bain photographed so beautifully. It was too bad she and Landau left due to some dispute. I never understood why! The series didn’t seem the same without them. You and your crew sure deserved an Emmy for that one! Superb Work, Ralph!

Ralph, I saw this episode as a child but until today, did NOT remember it as a Mission Impossible episode. For the last 30 years or so I was intrigued by that show that had trains, movie projectors and the fake crash. Ray Castro, whom I am working with on the Waltons Reunion, showed me this site, so by chance there it was… The Train. And with the added benefit of your wonderful detailed description on the making of it (I still can’t believe you got all that train yard footage in one day!). Thank you for making the episode that stayed burned into my memory through life and I am looking forward to reading and viewing information on many other episodes.

In his American TV Archive interview, Gerry Finnerman had some pointed comments regarding his brief ‘Mission: Impossible’ experience during Season One…and was delighted to return to ‘Star Trek’ afterward.

At 0:00 thru 0:05 of the 6th video, Barney and Rollin are looking through the warehouse window and see VW bus pull up to the train. Should I assume this was accomplished via post production work?

Ha ha, I never saw a hospital before that had neatly trimmed hedges lining the sidewalk and arches at the entrance (3rd video). What building was this?

I loved the phony language signs pasted on the train, vehicles, and buildings. Was “S-B Railts” and the rest spelled out in the script, or does the art director do this on his own?

This episode is on Youtube and someone posted a comment that William Windom’s haircut reminded him of Hitler! Maybe that was the plan. However, I thought it was interesting that the script allowed Pavel to have a tiny shred of decency (“it makes me sick” comment in 3rd video) in comparison to Androv.

Regarding the 6th video, it was NOT done in post production. It was one of the 69 shots we did the day we filmed at the train location. As to the signs, I’m not sure if it was scripted or the art director; my guess would be the script. Windom’s hair style was HIS choice. I told you he was an intelligent and exceptional actor.

Mr. Senesky,

I have been on a bit of Star Trek : TOS behind the scenes binge this weekend. I eventually found someone who posted on flickr about how you left Star Trek and i read your blog and then ventured to your site here.

Let me say, I have enjoyed reading about your jobs on some of my fave shows (Star Trek/Mission) but how cool is it that you directed one of my favorite Mission epps!! TRAIN was so fascinating to me because I so loved all of the gear used. I am a camera guy (Steadicam Operator, Jib, hard ped) and have been in this industry 20 years, and I absolutely LOVE seeing old tech like that used in this MISSION epp. The projectors with the HUGE vent to cool off the ARC lamp powering the projector, the projector guys who, by the way, looked like they knew what the heck they were doing, really sold the gag. Were they actual projector guys or just extras?

—–

How does working in Hollywood THEN compare to NOW? I would love to hear your perspective on that.

—–

Did you ever meet Lucille Ball? Was she a shrewd businesswoman? Seeing her on screen it is weird to see her as a studio head or that she and her hubby designed the 3 camera setup.

you may not even see this post, but I appreciate you sharing your thoughts on your productions.

I work in Hollywood so maybe our paths will cross one day…

Hi S-C: You ask a lot of questions so give me a chance and I’ll try to answer.

How does working in Hollywood THEN compare to NOW? I would love to hear your perspective on that.

I can’t really answer that because I have not worked in Hollywood for 26 years so I really don’t know personally what it is like today. I have recently directed a short 35-minute independent film (THE RIGHT REGRETS) that is currently being seen in Film Festivals. (A month ago it premiered at the Rhode Island Film Festival and won the Ambassador Award.) My crew were all very young (in their 20’s and 30’s) and very eager and talented. We filmed with a digital camera; our lighting equipment was inadequate as was the rest of our gear. The young crew’s dedication to the work was exemplary — much like I remember the crews of my time, and I think with the limited resources, they achieved some remarkable results.

I never met Lucille Ball. Actually according to what I know of Hollywood history it was Desi who was responsible for adapting the 3-camera mode of live TV to film. He foresaw the value of having films rather than kinescopes for future release.

And since you are working in Hollywood, you can tell me what it’s like today. If you’ve been there 20 years, has it changed — and how?