FILMED March 1976

One of my most pleasant memories is the production of JEREMIAH OF JACOB’S NECK, a one-hour pilot I directed for Edgar J. Scherick Productions. It was another in my string of family shows, this one with fewer kids than the others but embellished with the addition of a ghost. Although it was a 20th Century Fox production, I never went near their Pico lot. We were scheduled to film the entire show on location, and as I remember, Scherick’s production office was in the 9000 Sunset Boulevard building, which during pre-production was very convenient for me. It was practically at the foot of the hill from my home.

Casting and finding our locations were our two main concerns, with the locations being the more difficult, and for the locations our primary search was for a lighthouse with a lone family house nearby. Art Stolnitz, the line producer, and I started scouting the southern California coast from Santa Barbara to Long Beach. We spent a couple of days, didn’t find too many lighthouses and none with a lone house nearby; they all had large communities of homes in their vicinity. Then one day Art told me that we would be flying to northern California the next day. We flew to San Francisco the next morning, boarded a very small shuttle plane to Ukiah, then into a car for the final drive to Mendocino. I had never been to California north of San Francisco, so as we traveled the coast on the last lap of our trip, I was bowled over by the beauty of what I was seeing. As we rounded the last bend in the road, I got my first glimpse across the waters of the headland on which sat the charming community of Mendocino …

…and if Mendocino was to be our location, I knew what the opening shot of my film would be. A lovely lady whose name I have forgotten greeted us in Mendocino and acted as a one-woman film commission and tour guide. Our first stop was the lighthouse just north of what was their downtown, and we knew our search was over. The Point Cabrillo Lighthouse loomed on the coast and set back four hundred yards was a lone two-story white clapboard house. That would be where our family of four, newly arrived, would reside. For the interior scenes at the house our guide then took us to a large deserted house that sat at the end of their main street. It too proved to be perfect. Lots of rooms and they were large, better for filming than if we had tried to film in the house by the lighthouse. The rest of the day was a combination of scouting and securing the rest of our needed locations and learning the fascinating history of that unique community. Late afternoon Art and I were having a glass of wine in the local bar, killing time until we would be due back in Ukiah for our return flight to San Francisco, when we received word that we needed to leave immediately for the airport. Fog would be rolling in, and the flight would be leaving early. We immediately got into our car, headed for the airport and boarded the same small shuttle plane. There were only three of us on board: the pilot, Art and me. Soon after we took to the air the predicted fog engulfed us, and we were socked in. No longer was there a view through the plane’s windows. It was as if white paper had been pasted on to them. Art, who was a pilot, sat in the co-pilot seat, and I heard constant quiet conversation between the two men. I assumed that being a smaller plane, we could not rise above the fog because those lanes would be reserved for large commercial planes, so we were flying blind, hopefully with some instrument guidance. It was a long hour, but as we neared the San Francisco airport, we came out of the fog and made a safe landing. The flight from San Francisco to Los Angeles was far less hair-raising.

Casting went very smoothly. The network, who had final cast approval, had already approved Keenan Wynn, who was soon joined by Ron Masak, Arlene Golonka, Brandon Cruz and Quinn Cummings to make up the basic cast should the pilot be turned into a weekly series. The supporting players were set and on Sunday, February 29, the company traveled to Mendocino, where filming began the next day. The first shot I filmed and the first shot in the film was the shot I had planned as I saw Mendocino for the first time on that scouting day.

That was the 21st and last time I would work with art director, Richard Haman, whom I had requested. Richard’s first chore was redoing the exterior of the white clapboard house. The description in the screenplay was:

“a gray-shingled, early Victorian, somewhat ramshackle house that once sheltered the lighthouse keepers.”

Obviously there was some needed conversion work to be done to the immaculately painted structure. The current owners living in the house approved, so Richard had his painters redo the exterior. To meet the demands of the screenplay the house was dirtied and “ramshackled” down. After we finished filming, the house was repainted and restored to its original state, so the owners were delighted; they ended up with a freshly repainted home in addition to the fee they received for allowing us to film on the premises.

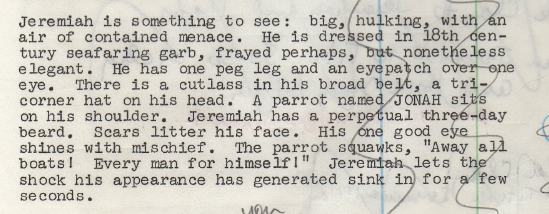

The ghost also needed some revamping. The screenplay description of him:

I sometimes wondered if the people at the network ever bothered to read the scripts before they made their final casting decisions. Both Edgar Scherick and I agreed Keenan Wynn was a superlative actor, but except for the parrot on his shoulder he did not physically fulfill the description in the screenplay, not to mention the difficulty in production that a peg leg would create. Peter Benchley’s pirate Jeremiah Starbuck became our sea captain Jeremiah Starbuck.

The elderly couple at the post office were locals who lived in Mendocino; the post office mistress was my pal, Amzie Strickland in one of her frequent appearances in a production I directed. This is another of those times when I regret not having kept a journal, but as I remember, the beautiful Victorian interior of the Mendocino Hotel had a caged counter in the lobby that I thought would make a fine post office, but the exterior of the hotel couldn’t be used for the scene when the couple exited. So we found another building for that scene, put up a sign and a flag, and presto – the exterior of the Jacob’s Neck Post Office was created.

The antique bicycle for the post office mistress presented a problem. When Amzie mounted to ride it, the bicycle proved temperamental; it seemed to have a mind of its own. It wouldn’t go in the direction she was steering, and it kept trying to throw her off. But I was not about to give up. The prop crew was called in, additional wheels were added and Amzie’s Abby went bicycling down the dusty road on her newly created tricycle.

Another difficult location we needed was postmistress Abby’s house, both exterior and interior. We had a lot of filming to do there, but we were taken on our scouting day to a charming small house with a spectacular view. The owner’s were agreeable, and a commitment was made.

This was a reunion for Brandon Cruz and me. It had been six and a half years since I had directed him as seven-year old Eddie Corbett in THE COURTSHIP OF EDDIE’S FATHER. Now two months from his fourteenth birthday I was directing him as Clay Rankin, the shy teenager with a precocious younger sister. One day during production someone on the staff told me they felt sorry for Brandon. Every evening he was having dinner with his grandmother (I think she was the adult required by law to accompany him to the location), Quinn and her mother. It was suggested that I take him to dinner to give him a break from all those females. I gladly complied.

Quinn Cummings, like her character of Tracy, was a very bright, precocious little girl. She was eight years old when we filmed JEREMIAH. The following year she appeared as Marsha Mason’s daughter in Neil Simon’s THE GOODBYE GIRL, the film for which Richard Dreyfuss won an Academy Award. I read an interview of Quinn at that time in which she was asked to what she attributed her success. She replied, “I have a pushy mother.”

Edgar Scherick was a fine producer, always on the set, very supportive and never interfering. 1976 was a time that was pre-cellphone. I was amused that whenever we arrived at a new location or at a restaurant to dine, Edgar would immediately excuse himself to go make a phone call. That went on for the full ten days of filming. The last day we ended working in a stable where Richard Haman had created sets for the tunnel cave the children were trapped in and for the carpet in Abby’s house with the unseen Jeremiah’s feet leaving indentations. As we arrived at the stable, one of the employees called out, “Telephone call for you, Mr. Scherick.”

Keenan Wynn was true show biz royalty. The son of legendary Ed Wynn, his career spanned more than half a century. He rarely had a lead role, but he almost always received prominent billing. Keenan told me a wonderful story of his youth. Ed Wynn, although he was Jewish, was welcomed into one of the segregated clubs in Los Angeles. One day he took young Keenan with him to the club, and there were some objections when the young boy put on a bathing suit in preparation for a dip in the pool. The elder Wynn interceded, saying, “He’ll only go in the water up to his waist. It’s all right. He’s only half Jewish.”

On our scouting day we decided on a walk-in safe for our room for Jacob’s Neck Archives. It was small, and the loaded shelves seemed very appropriate, but the floor of the safe was totally filled with – I can find no other word – junk. Instructions were given that the junk needed to be cleaned out so we could install the props we would need for filming. On the scheduled day for filming, we arrived to find the safe in the same state; it had NOT been cleared out and redressed. Edgar Scherick panicked, as I calmly started overseeing the clearing out of the extraneous objects and the dressing of the set. Edgar couldn’t understand why I was not shouting and reacting more emotionally to the situation.

I was amused when I learned that after the previous scene of Keenan and Ron, one of the network people at the screening of the dailies complained, “I can’t see their faces.”

I thought Ron Masak looked a lot like Lou Costello, but he was taller and looked more like a leading man. In the final battle between Ron and Alex Henteloff (the bank robber), when Ron was pushed into a chair, the action was overly energetic on the first take, and the chair tipped over. The lady of the house who was present became very agitated. She demanded that we cease filming and leave. I don’t remember what I said, but I somehow quieted her, assured her that there would be no damage to her possessions, and we were allowed to finish. I remember Ron quietly commending me for that as we returned to filming. Three years later we worked together again on an unfortunate project. When I was summarily fired, Ron called. He wanted to quit, leave the film in protest. I convinced him to stay on. I’ve never forgotten that phone call. He really was a mensch!

In May when CBS announced their schedule for the following season, JEREMIAH OF JACOB’S NECK was not on it. Sometime later I was near CBS at Beverly and Fairfax when I bumped into David Shaw, a fine writer. We exchanged the usual amenities, checking on each other’s recent activities. I told David I had directed the pilot, JEREMIAH OF JACOB’S NECK. I’m not sure how David knew; I assumed he had been involved in some executive position at the network, but I was startled and dismayed when he replied, “Oh, that one was dead on arrival.”

Very enjoyable to watch and read. Wasn’t this pretty much the plot of “The Ghost and Mrs. Muir”?

Only the ghost.

It’s great that you had the opportunity to work with Brandon Cruz again during this pilot. I’ve been one of his fans for a long time and I hope I can meet him some day, if he’s ever in New York with other celebrities for an autograph show.

What fun to see Tom Palmer as “Crabtree” and of course, Amzie. I met Tom at your home on Sunset Plaza – he was a kind and gentle man – am I correct in recalling he was also a Casting Director?

And also fun to see Ralph Ferrin credited as your First Assistant Director – he was our alternating First on THE WALTONS – also a kind, gentle and quiet man who proved that an efficient First Assistant need not be an ogre.

No wonder these are pleasant memories – you surrounded yourself with pleasant people.

I poked around a few online newspapers to pinpoint the time and date this was broadcast, which was Fri., Aug. 13, 1976 at 8 PM Eastern. In the process, I came across a review of the program in the 8/13/1976 issue of the Milwaukee Sentinel; its writer dropped a 10-ton weight on it.

Aside from parallels with ‘The Ghost and Mrs. Muir’, critics were also reminded of the mob paranoia scenes in the coastal village from ‘The Russians are Coming The Russians are Coming’ (filmed partly in Mendocino, too). I saw that movie on TV once more than 30 years ago and wasn’t crazy about it. IMDB says that story was based on a novel called “The Off-Islanders”, by Nathaniel Benchley. Yes, he’s the father of Peter Benchley.

What a wonderful experience and great cast and crew to work with. I had high hopes this pilot would be picked up. Sure enjoyed watching. Ralph and I did an “Insight” together. I’m glad he remembered me. Then and now.

.The INSIGHT was THE MAN WHO WENT BLUE SKY.

They used my house at Point Cabrillo in Fort Bragg. I only got to watch the pilot one time and would love to watch it again. They also used me and my husband along with our car in a seen where there was a crowd of people. I did not see myself but my husband was very visible. Please tell me if this pilot can be purchased and through who. My husband was in the Coast Guard at the time. I know he would also love to have a copy along with my three kids. The oldest also remembers it,the next two children weren’t born yet . Nancy l. Posey, but I am now Nancy l. Sharkey. I lived in Fort Bragg for about 9 years. I love this place and still visit often. My daughter says she has pictures of the actors taken during the movie. You can walk down and enjoy the light house as it is now a small gift shop.So when your in Fort Bragg be sure to visit Point Cabrillo where this movie was taken. At the gift shop they knew nothing about this pilot taken very sad. Nancy

I have google-checked to see if JEREMIAH is available anywhere for purchase or to view online with no success. However, the clips above are MORE than just random clips. They are the complete episode as aired.

One of the really fun shoots I was ever on Wonderful location, wonderful cast…all involved fun to be with and a GREAT director…God Bless

And you were a great contribution to the fun and the resulting film.

Hi! Thank you for chronicling your works. I’ve been searching for JofJN for a long time, just recently starting up again, and came across your site. My grandfather was the elderly man in the post office, though he was only 63 at that time. The building used for the post office was the office and production site of the local newspaper, the Mendocino Beacon, of which my grandfather was the publisher. Thank you also for sharing the clips. I had never seen JofJN before, so it is a treat to finally be able to watch. Thank you again.

And thank you Colin for sharing your story with me!