Ben Brantley started his review in the New York Times for the 2018 revival of THE ICEMAN COMETH writing:

If you have a good time at a production of “The Iceman Cometh,” does that mean the show hasn’t done its job? I was beaming like a tickled 2-year-old during much of George C. Wolfe’s revival of Eugene O’Neill’s behemoth barroom tragedy, which opened on Thursday night at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theater, with Denzel Washington more than earning his salary as its commanding star.

A sustained grin may not seem an apt response to a play in which desperate, drunken denial is the given existential condition, and suicide and murder are presented as perfectly reasonable life choices for anyone who sees the world clearly..

I’ve been waiting close to 60 years to read a review like that of a production of THE ICEMAN COMETH! In my far distant past I had my own experience with the Iceman coming – except in my case it was the Icemen.

Let me start by taking you back to an August evening in 1961.

The setting: the theatre lobby of Schoenberg Hall on the U.C.L.A. campus.

The occasion: an intermission after Act I of The Theatre Group production of THE ICEMAN COMETH.

John Houseman and I were speaking with Jeanne Cagney, James Cagney’s younger sister. Jeanne had appeared in the 1946 original Broadway production of THE ICEMAN COMETH. With sparkling eyes and a broad smile she asked, “Where did all those laughs come from?”

To seek the answer to her question, let’s travel back a little further to a day in June on the MGM studio lot in Culver City. I was in the early stages of being the Assistant to the Producer on the new television series, DR. KILDARE. One day I bumped into John Houseman, who was at the studio producing ALL FALL DOWN. I had known John a couple of years earlier when I was on staff and he was one of the producers of CBS’s PLAYHOUSE 90. I had recently read that John was going to be directing a Theatre Group production of THE ICEMAN COMETH. I congratulated him and told him I hoped he would enjoy doing it as much as I had in the production I had directed. He asked me where I had directed that production. I told him it was in Gilmore Brown’s Playbox at the Pasadena Playhouse. His response: “You directed that production?” It was a very short time after that when he asked if I would come aboard as the co-director for his upcoming production. Naturally I said, “YES!”

Still seeking the answer to Jeanne Cagney’s question let’s go back to December, 1957, when the Iceman entered my life. Six months earlier I had joined the staff of PLAYHOUSE 90 as they were preparing for their second season. I was secretary to Russell Stoneham, one of the assistant producers on the series. Gilmore Brown, the founder of the Pasadena Playhouse, phoned me one day. I had by that time directed five productions in his PLAYBOX, a small intimate theatre adjacent to his residence. Mr. Brown had a request. He asked me if I would direct another production for him in the Playbox.

“What play, Mr. Brown?” I asked

“I don’t want to tell you until you tell me you’ll do it. Will you?”

“But what is the play, Mr. Brown?”

“I’ll tell you after you agree to do it.”

That back and forth conversation continued until he finally told me the play was Eugene O’Neill’s THE ICEMAN COMETH. I immediately said of course I would direct it. I would be honored to direct it. Mr. Brown then told me he had cast one actor in the production, but he had not assigned what role he would play. That would be up to me. The actor was Onslow Stevens. You may not recognize the name, but Onslow Stevens had starred in movies and on Broadway. I remembered him from several appearances on the main stage of the Pasadena Playhouse when I was a student. I especially remembered his RICHARD II, which he both starred in and directed. Mr. Brown also told me that I would have to cut the script. That was a surprise. I knew enough about Eugene O’Neill to know that he never allowed his scripts to be cut. Although he had died, his widow Carlotta and the O’Neill estate continued that control.

There were 19 roles in the play. Once I had reread the play, I decided that Onslow Stevens would play the cynic, Larry Slade. I had a little less than 4 months until my Sunday night open auditions that would be held in the main stage theatre of the Playhouse. To get started the two tasks at the head of my to-do agenda were to cut the play and to cast the other major role of Hickey, the hardware salesman.

I had never met the actor Paul Langton, but I had seen him many times on the Playhouse main stage when I was a student. I had also seen him in Chicago in the National touring company production of DEATH OF A SALESMAN (he played Biff). I met him in his home, and unexpectedly it was a very fortuitous meeting. He was not able to accept the invitation to play Hickey, but he had some very helpful information about the play. He told me that during the tour of DEATH OF A SALESMAN Eugene O’Neill came to see Thomas Mitchell (he was starring as Willy Loman). He wanted Mitchell to star as Hickey in a revival of THE ICEMAN COMETH. Mitchell was reluctant. For one thing he thought the play was too long. O’Neill, who never allowed his plays to be cut, told Mitchell he could cut the play. He suggested that the way to cut it would be to eliminate a character and a story line. I was excited and relieved. I now had a direction to take in cutting the script.

As I was to learn, the reason for cutting the script was not aesthetics. The PLAYBOX was no longer in its original location, the one where as a student a decade earlier I had acted in a production and where starting in 1955 I had directed 3 productions. But the previous year (and I never discovered the reason) Mr. Brown moved the theatre. He purchased a beautiful home that had belonged to a professional musician, a pianist. The ground floor was a large concert hall with one end raised for his grand piano. That concert hall was to be the new PLAYBOX theatre. The second floor had been his living quarters. That area was to be the cast dressing rooms. (Living quarters for Mr. Brown were added at the rear of the building.) I was acquainted with that theatre. The previous year I had directed a production of BELL, BOOK AND CANDLE there. What was the problem, the reason for cutting the script? The theatre was in a Pasadena residential neighborhood where activity at the theatre had to have a curfew. All activity had to stop by 10:30 PM. If performances started at 8:00 PM, there was no problem. But the running time for an uncut THE ICEMAN COMETH was 4 hours. Our plan was to start performances at 7:00 PM. That meant, allowing for two 5-minutes intermissions, I had to cut the play’s length to a maximum 3 hours and 20 minutes.

The play takes place in Harry Hope’s bar, where Harry and 15 alcoholics are awaiting the arrival of Theodore “Hickey” Hickman, a salesman. Each of the characters is delusional with a pipe dream about the future and a past they ceaselessly speak about. I decided I could eliminate 2 characters–the Boer, General Piet Wetjoen and the British Captain Cecil Lewis, the pair with a joint history from South Africa. The printed play was 257 pages. For the next 4 months I still had my duties at CBS on PLAYHOUSE 90 but my evenings and weekends were devoted to cutting. That involved more than just eliminating all of the speeches and actions of the two characters. Sometimes what they said was needed information and had to be retained and assigned to one of the other characters. And no one could ever accuse Eugene O’Neill of NOT being verbose. Some judicious editing was also going to be necessary to get the script shortened.

It was imperative to cast the role of Hickey as soon as possible. The character doesn’t make his first appearance until the end of Act I, but he is seldom off the stage in Acts II and III and in Act IV he has a 15-minute monologue. When I was a student, Bill Greer had been on the Playhouse staff as a director, teacher and the Dean of Men. As a student I didn’t have any association with him in any of those positions, but I remembered seeing a student production he directed in one of the Balcony theatres. I don’t remember the name of the play, but I think it had a southern rural setting. I was impressed with the caliber of the student performances and intrigued when his staging in one scene had his leading man lie down flat on his back on the stage floor. That just wasn’t done back then. (Sidebar comment: I did it twice in my theatre productions; once in a production for the Mason City Little Theatre and again two years later in THE CIRCLE on the Playhouse main stage.) Since then he was no longer on staff at the Playhouse and under the stage name Dabbs Greer he had embarked on a successful screen career. He was my next choice for Hickey and fortunately for me he accepted. Now I just had to tend to my CBS duties and cut the script.

On a Sunday sometime in mid-April I got into my 1950 Dodge and headed via the Pasadena freeway for the Playhouse. I only got as far as Highland Park when my Dodge started to sputter and I barely got off the freeway. Since cell phones were not yet the vogue, I found a pay-phone and called my friend, the actress Madge Blake (she lived in Pasadena) and she rescued me, took me to the Playhouse for the auditions and stayed so she could take me back to my apartment afterwards. The next day I learned my Dodge had not just sputtered in Highland Park, it had died. The following few days besides working I was involved buying a new car (a Renault Dauphine). The next few weeks I completed casting the remaining 15 roles and the first week in May began the 6-weeks of rehearsal.

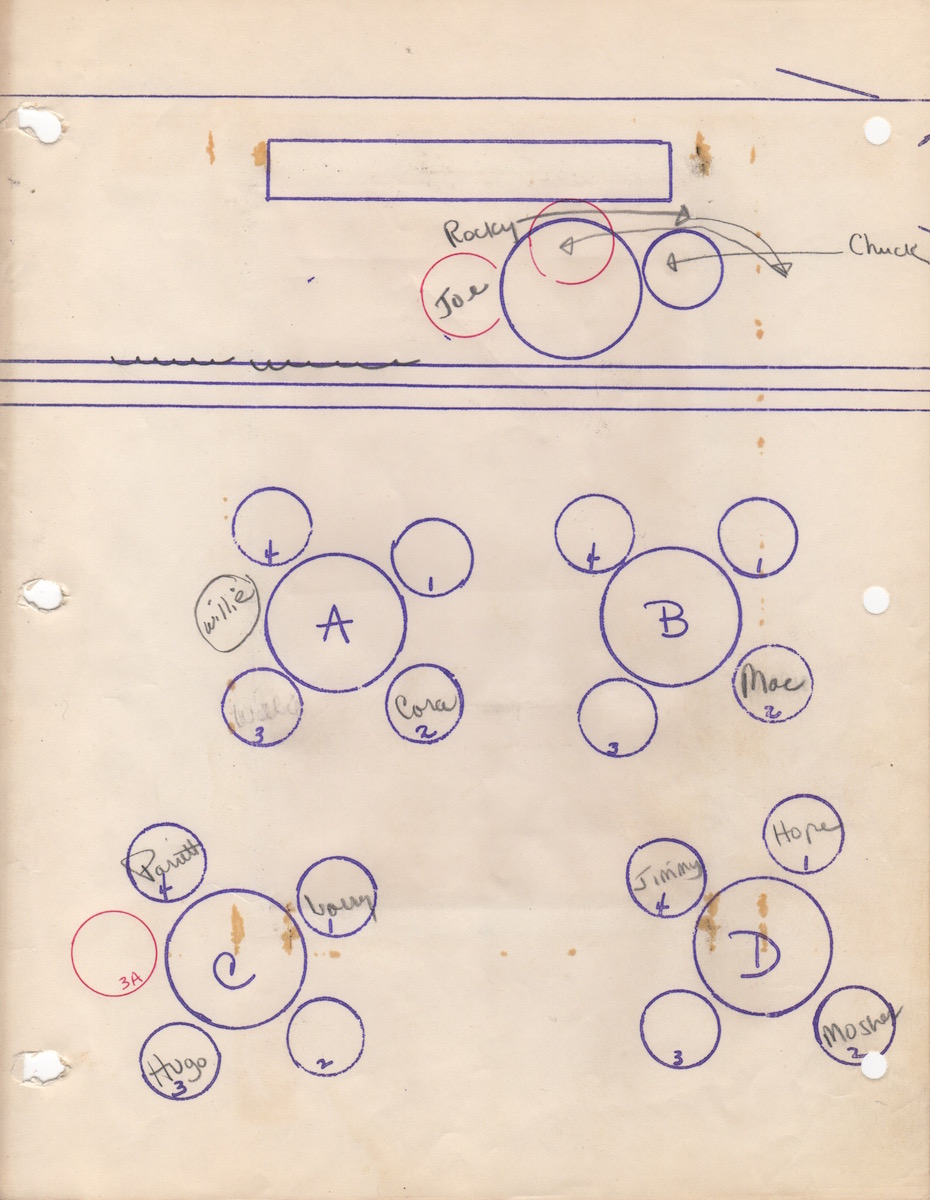

How to turn a beautifully wood-paneled concert hall into a seedy, rundown Westside Manhattan saloon! I put a bar and a table with chairs on the raised area where a grand piano had once sat. On the lower level I had 4 tables with many chairs. And I planned to keep the lighting low.

As in the original PLAYBOX location the seating for the audience was NOT conventional bolted down theatre seats. There were 50 upholstered chairs that could be arranged to accommodate the play’s set.

To return to Jeanne Cagney and her sparkling eyes and a broad smile (as) she asked, “Where did all those laughs come from?”

My concept for the production: When the lights faded up for Act I, I wanted the lighting to be a cold blue-white daylight to reveal 14 derelicts somberly seated at the tables. They would seem to be more like tombstones than humans. That was the reality. I wanted to take the audience past that reality, that objective first impression. As they started to speak and move around, I wanted the audience to become acquainted with those 14 derelicts, but to view them compassionately, sympathetically as a lot of lost souls, surviving with the aid of booze, the sanctuary of Harry Hope’s saloon and most importantly their pipe dreams. (Definition of pipe dream: false hope, delusion, daydream, castle in the air, pie in the sky). On this particular day they were excited as they awaited the imminent arrival of Hickey, who as one of the characters says, “…Hickey’s a great one to make a joke of everything and cheer you up.” And I would let the opening cold lighting gradually warm to a salmon-pinkish glow.

But the play isn’t a comedy. The Hickey who arrives is not the usual jokester. He tells them that Evelyn, his wife, has died, he has had a moment of clarity, is now sober and is determined to help all of them face life’s reality as he has done. He explains that they are after delusions and empty dreams and he promises them peace if they give up their pipe dreams. He is relentless as he confronts the group, collectively and individually. He succeeds, but the group becomes despondent, downtrodden, suspicious, depressed. As Larry, the cynic (Onslow Stevens’ character) says, “…I feel he’d brought the touch of death on him” And the lighting would return to the cold blue-white daylight that opened Act I.

The group’s reaction upsets Hickey. They haven’t reacted as he expected. In the final Act, he launches into a long 15-minute speech about his life with his beloved wife Evelyn. He tells them of how she loved him even though he was away for long periods, involved in affairs, living a depraved life, and how she always believed him when he said he was going to change, and of how he eventually felt intense guilt and resented her for this.

And here let the words O’Neill had Hickey say take over:

HICKEY: …So I killed her. And then I saw I’d always known that was the only possible way to give her peace and free her from the misery of loving me. I saw it meant peace for me, too. I remember I stood by the bed and suddenly I had to laugh. I remember I heard myself speaking to her, as if it was something I’d always wanted to say: “Well, you know what you can do with your pipe dream now, you damned bitch!” (He burst into frantic denial) No! That’s a lie! I never said – Good God, I couldn’t have said that! If I did I’d gone insane!

As two policemen (Hickey had phoned them, telling them to meet him at Harry Hope’s Bar) take Hickey away, under arrest for murder, Harry Hope tells the now silent stunned denizens of his saloon that Hickey is indeed crazy, had to be crazy. The group eagerly grasps onto this explanation and return to their drinking—and to their pipe dreams as the now warm salmon-pinkish lights fade to end the play.

Our 6 weeks of rehearsal began in the PLAYBOX theatre where we would be performing. Rehearsals were called for 7:00, but rarely started on time. Our rehearsals were Monday through Friday evenings and (when possible) Saturday and/or Sunday during the day. I broke the 4 acts into 41 scenes. That way l I did not require the entire cast at each rehearsal. But always, because of that 10:30 curfew, there wasn’t enough time to do what had to be done. There was a large room on the 5th floor of the Playhouse used for dance classes and rehearsals for main stage productions. I learned it was going to become available and made arrangements for our rehearsals to be transferred there. Imagine my chagrin the first night we took over the room to have someone arrive at 10:30 and tell us we had to leave. That space also had a curfew. After a few evenings we returned to the PLAYBOX. At least there we would be rehearsing in our actual setting.

Other problems arose. There were 3 women in the cast–-all playing prostitutes. It did not take many rehearsals for me to realize one of the trio was not up to the task. It is not easy to fire someone in a cast, especially if they are volunteering their services without pay. But I did it as gently as I could, the actress was gracious and understanding and the recast actress turned out just fine.

I have always been fascinated by actors’ various and individual approaches to the craft of acting. Al Lurie, the actor playing Rocky, one of the bartender-pimp characters in the play, told me something very interesting about Onslow Stevens. Al had a few good scenes seated at the table with him. Al said that when Onslow was speaking, his eyes were vibrant and alive. When he finished and it came time for Al to speak, he said Onslow’s eyes went totally blank. He looked like a blind man! They lit up when he spoke again, and then went blank when he finished speaking. Al wasn’t complaining or asking me to correct the situation. It was Onslow’s approach to acting. It didn’t make it easier for the actor in the scene with him; it wouldn’t have worked onscreen, but it worked onstage. The audience couldn’t see it, and Onslow was truly brilliant.

The recasting of the third prostitute was not the end of my casting problems. About 4 weeks into rehearsals, the actor playing the revolutionary anarchist suddenly, without any notice, quit. Vince Bowditch, a staff director and teacher at the Playhouse, was recruited, joined the cast and accepted the challenge of learning the lines, the cues, his character’s stage business–-all of that as he was developing his character, everything his predecessor had had 4 weeks to accomplish–-all of that catch-up as we were in the final 2 weeks before we opened.

And then there was an experience unlike any I had had before or would have in my future. It occurred on one of those nights in the 5th floor rehearsal room. (That was still fairly early into our 6-weeks of rehearsal.) With about an hour to go I planned to spend the remaining time working on Hickey’s long 4th act monologue. All of the cast rehearsing that night had left except for Dabbs Greer and Onslow Stevens. Bill (and I always called Greer “Bill”) had done a section of the long monologue and I was commenting with some suggestions, when he flared up at me. He said he was sorry he had accepted the role. He realized the role was unplayable. He would continue, but further delving into characterization was useless. All he would do—all he planned to do–was learn the lines and spit them out. And all of this was pouring out of him with anger and rebellion. I was dumbstruck. I frankly didn’t know what to do, what to say. Then Onslow, who had been sitting quietly at his table, entered into the conversation. Bill continued his onslaught, but it was now aimed at Onslow, not at me. And that veteran professional managed to lower Bill’s diatribe into a calmer conversation. Soon I was able to come back into it, and as Bill and I calmly discussed Hickey’s speech (and I didn’t realize it at the time) Onslow disappeared from the room. It was only later that I understood the rescue act that had just occurred.

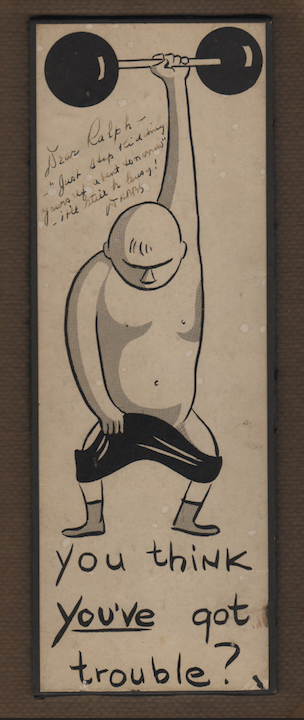

The following evening Bill brought me:

Dear Ralph

“Just stop kidding yourself about tomorrow” –

it’ll still be lousy!

Dabbs

“Just stop kidding yourself about tomorrow” – one of Hickey’s lines from the play.

We continued with rehearsals. For Bill there was no more further delving into characterization was useless, no more just learn the lines and spit them out. We approached the final week before opening, but without ever being able to do a complete run through of the entire play.

Mr. Brown had not attended any rehearsal. He was set to come to our final dress rehearsal the night before we opened. I pleaded with the cast to come early enough so they would be made up and in costume for us to start performing at 7:00. They did and a few minutes before 7:00 they were ready. Mr. Brown appeared and greeted the cast with a welcoming address, words of appreciation and his usual substitution for “Good Luck“ – “Have Fun.” He spoke for 15 minutes. At 10:30, the final scene not ended, we had to stop. From Mr. Brown there were no words of criticism—just a kindly, “You’ll have to cut.”

I didn’t! The following night we started the performance at 7:00, and at 10:30 our production of THE ICEMAN COMETH, in front of our first audience, played from the beginning of Act I to the end of Act IV for the first time.

There was a lovely lady, a white-haired Pasadena matron, who was around during our rehearsals and run. I’ve forgotten her name, but she was a longtime patron-supporter of the Playhouse, who had a close relationship with Gilmore Brown. She told me something very interesting. I was aware the selection of plays for main stage productions had changed in the decade since I graduated from the Playhouse School of Theatre–that it was no longer Gilmore Brown making the selections but Charles Prickett, the man responsible for the financial running of the institution. She told me that Gilmore Brown was hoping that this production of THE ICEMAN COMETH would move to the Playhouse main stage and could result in his reclaiming his former power. Was that Mr. Brown’s pipe dream?

60 years later I have another question. Why was Onslow Stevens, on that eventful evening in the 5th floor rehearsal room, still there after the cast had been dismissed? His character had no interaction with Hickey during the long monologue. He could have left with the rest of the cast. Which leads to another question. Was there a dual-purpose to Mr. Brown’s pre-casting him before he asked me to direct THE ICEMAN COMETH? Onslow had been closely involved with the Playhouse since 1926. Was Onslow’s rescue of the less-experienced director something Mr. Brown prepared for?

The PLAYBOX ICEMAN did not move to the main stage.

If it was Mr. Brown’s pipe dream …

Mr. Brown died two years later.

I was proud of our PLAYBOX production of THE ICEMAN COMETH, but I was aware of deficiencies. The production 3 years later corrected some of those, but I felt in the roles of Hickey and Larry it lacked performances as powerful as the ones Dabbs Greer and Onslow Stevens had given in the PLAYBOX production. So without realizing it, I too may have been harboring a pipe dream—a chance of trying just one more time. Writing this post has been more difficult than any of the 208 that preceded it. I truly have emotionally relived many of the scenes I’ve described. But now that I’ve reached its conclusion, the end of this existential excursion, I’m feeling a closure—that my pipe dream has been put to rest.

Very enjoyable – always look forward to your new posts Mr Senensky – and Paul Langton and Dabbs Greer are two of my favorite character actors.

Wonderful, Ralph! While reading this I have the luxury of hearing your voice telling me this story, sitting at your kitchen table in Carmel. It remains fascinating in both versions!!

Side note: I had the great honor and pleasure of working with Paul Langton in 1955. I played his daughter in an Albert McCleary’s NBC MATINEE THEATRE. I had met you at the PLAYER’S RING THEATRE just a year before, 1954! We’re still here!! You and I, that is!

As always your insight is most enjoyable.

Mr Senensky ~ I enjoyed reading your latest article very much ! Thank you for another well written piece of Entertainment History.. I hope that some WISE Publisher will appreciate your writings as much as I do… and put out a book !

– All the Best , Sir ! And Please keep these Wonderful pieces coming.

Hi Ralph — We exchanged messages related to Star Trek here a few years back (when you asked me whyever would I choose to go by “Ralph,” my middle name, when I could have gone with “Carl,” my first). Twice in the past week you have crossed my mind, so this is no more, or less, than a “hello” and “how are you?” So glad to see you’re still enriching this amazing historical record. Hope you are happy and well!

And this is no more. or less, than a “hello”, “how are YOU?” and I’m fine. Good to hear from you.

Mr . Senensky,

I’m a big fan of the first 6 or 7 seasons of ‘Perry Mason’, I’m curious if you were ever approached to work for that Production house. If not, Did you ever cross paths with Raymond Burr ? .. Many of the Great actors mentioned in your various posts, appeared on ‘Mason! ~ Thanks Sir !

I never directed a PERRY MASON but I did direct Raymond Burr in 2 episodes of IRONSIDE in its 1st season, which began the year after PERRY MASON ended.

… of course Raymond Burr was BIG in ‘Rear Window’ … ; )

I corrected BOTH of them!

Just being Silly Sir ! .. Have a Nice Day … : )

Hello, Mr. Senensky! I am so thrilled to know that you were good friends with my fabulous Grandmother, Madge Blake… Thank you for sharing your memory of her in the story above! She was my greatest role model for handling “showbiz” with kindness, humility, warmth, and humor. I miss her so. All my best to YOU… XO, Alison Blake

Wow, reading your thoughts about Iceman was almost as wrenching as watching the play. You experience with Greer and Stevens was actually understandable – I can see that confrontation coming out of actors trying to get this play together. That experience would make an interesting play all by itself.

I saw the Denzel Washington production, had a reaction similar to Brantley’s, was exhausted by the time it was over – and wondered how I might see it again, directed by someone else. I may get that chance if we ever get out from under COVID but I’m sorry I wasn’t around to see your take on it. It struck me as the kind of play I would like to see from different directors’ viewpoints.