Filmed October 1964

Don’t touch that dial! By 1964 that could have been the mantra of the three television networks. You see television had become BIG BUSINESS. High ratings meant higher advertising rates, which translated into higher earnings. Since all programs began on the hour or the half hour, if a network had your set tuned in to them, they didn’t want to lose you as the next program began; so the new program had to grab your attention and your interest instantaneously and hold you. That was easy for action adventure programs (cop and detective shows, westerns), which usually started with a crime. Dramas with quieter opening sequences solved the problem by showing a grabber, a climactic scene from later in the show that ended in a cliffhanger. That was the format for Quinn Martin’s THE FUGITIVE.

In 1932 MGM produced the first all-star cast film, GRAND HOTEL starring Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, Joan Crawford, Wallace Beery and Lionel Barrymore. At the box office any of the film’s five stars was insurance for a film’s success. Putting all of them in one film was a true innovation. DETOUR ON A ROAD GOING NOWHERE, my second outing on THE FUGITIVE, had the same multi-character format as GRAND HOTEL. I thought the show could have been subtitled “mini-GRAND BUS.” And if the cast didn’t reach the dazzling heights of the Metro film, I think for television in 1964 it was pretty high-powered. Headed by series star, David Janssen the guest stars cast were Geraldine Brooks, a star since her 1947 breakthrough performance in POSSESSED, one of Joan Crawford’s most impressive films; Lee Bowman, a Hollywood fixture since his film debut in 1937 and leading man at some time to Jean Arthur, Rosalind Russell, Lucille Ball, Doris Day, Rite Hayworth, Susan Hayward, Myrna Loy and Ann Sothern; Phyllis Thaxter, who had been around since 1944, when she came to Hollywood after playing the title role in the national touring company of CLAUDIA, the role Dorothy Maguire had played on Broadway. One of the pluses in directing THE FUGITIVE was the varieties of film genre it presented. WHEN THE BOUGH BREAKS had been an intense film-noirish interior drama with Kimble involved with one character. This episode, like GRAND HOTEL, was a multi-character mélange of inter-reacting relationships.

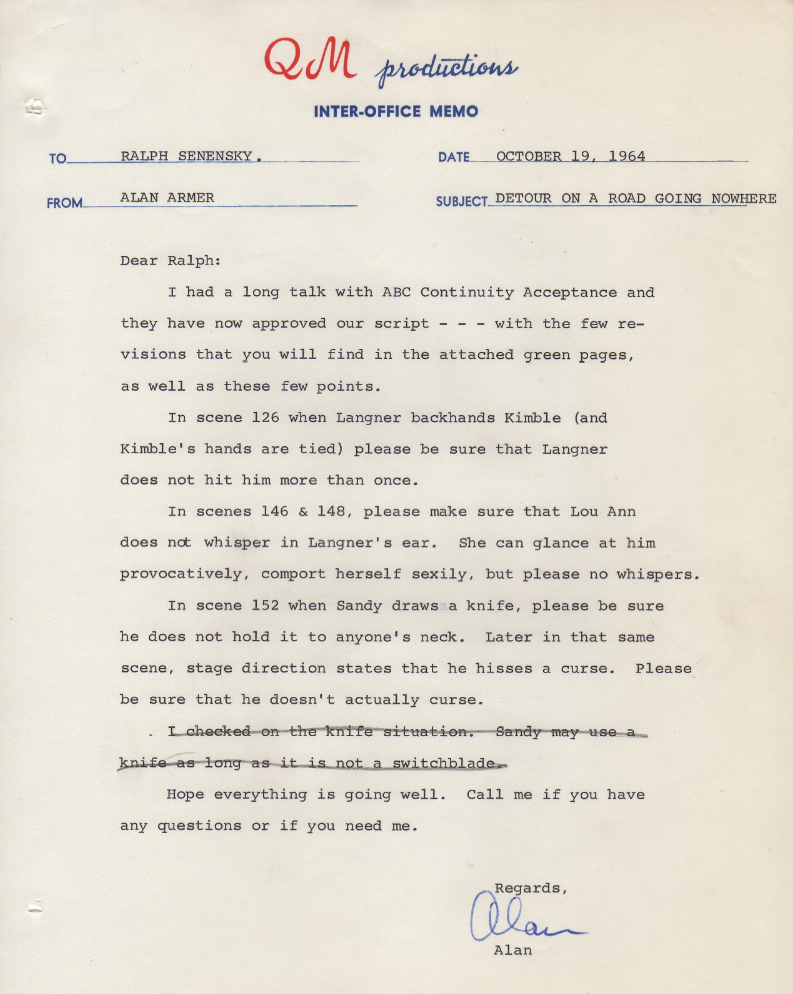

What was it about knives that so upset the network continuity acceptance departments. On my first show, JOHNNY TEMPLE on DR. KILDARE, there was no fuss when the script called for young Johnny to SHOOT his father, but since it was established in the script that Johnny had an obsession with knives, it was decided the injury to the father should be by a knife, That’s when the concern bells started clanging. On DETOUR… Dorothy Brown at ABC didn’t feel the need to descend on the production office as she had done for THE BULL ROARER episode of BREAKING POINT, but she did send some warnings to Alan Armer, which he relayed on to me.

This episode could have been filmed almost entirely on location. The settings called for were a picturesque mountain resort, mountain roads and finally the mountain road site where the bus is stopped by a landslide. If this had been a feature film, I would bet it would have been filmed on location. But since more than half the script was at night, the television schedule and budget couldn’t accommodate that. It was decided that once the bus had broken down, the balance of the show would be filmed at the studio on a green set. That was to be another major first for me, and one that had me concerned. Of less concern was finding Indian Lake Lodge, the mountain resort. I just returned to the Girl Scout camp in Bronson canyon I had used ten months earlier for the Guide Dog School setting on BREAKING POINT.

We cast Geraldine Brooks to play Louanne. A few days later her agents notified us that she had been offered the role of co-star to Robert Taylor in a feature film, JOHNNY TIGER, so we released her from the commitment. In casting Elizabeth Allen to replace her, visually we were cloning her appearance.

The camera crew didn’t object too strenuously, but they weren’t too happy with my choice of the site for that scene. It was at the top of a long stairway, and the heavy camera had to be carried up that stairway. But I thought it was such a good angle for the opening shot of Kimble ascending. Besides I remembered what director of photography Jack Marta had told me when we worked together on ROUTE 66: “You plan your show according to your vision. It is up to us, the crew, to deliver it.”

The Girl Scout camp was the perfect location. It had the required buildings, beautiful wooded surroundings, a tennis court and a swimming pool. The young Doll was Lana Wood, Natalie Wood’s kid sister.

Walter Brooke was such a fine actor. This was our first film collaboration, but I met Walter twelve years earlier. I was the assistant director at the Chevy Chase Summer Theatre in Wheeling, Illinois, a suburb north of Chicago. I was assigned to stage manage an incoming package production of THE SECOND MAN starring Franchot Tone with Betsy von Furstenburg, Irene Manning and Walter Brooke. Walter told me then that the previous year he had been a final contender for the role of Biff in the film production of DEATH OF A SALESMAN. It all depended on who would be cast as Willy Loman. When Fredric March was cast, Kevin McCarthy, who looked more like he could be his son, got the role. Walter also told me Franchot Tone had confessed to him that in his early years he had been the great white hope of Broadway. But regretfully he had not lived up to that promise. I remember the opening night performance of THE SECOND MAN. The theatre was a very large tent, staging in the round. I was in the control booth when during a scene between Tone and Walter, one of them did something off script which broke the two of them up in laughter. The audience responded by joining in the hilarity. Tone and Walter staggered around the stage unable to control themselves and the audience went wild. I have to admit that in the control booth, I too joined in the laughter. Only the next night when they did it again did I realize it was not a breakup, it was part of the staging. And they did it night after night through the entire run. Walter also told me the champagne used on stage was real champagne; Franchot Tone didn’t like the taste of ginger ale, which was usually used.

Walter is the manager of the Lodge

I wanted to cast Paul Bryar as the bus driver, but when I made this suggestion to casting director John Conwell, he told me Paul was on Quinn Martin’s “don’t use” list. (I might add, I learned later that was a fairly long list.) It seems that years before on a production of Quinn’s THE UNTOUCHABLES, Quinn had visited the set one day, saw Paul joking around and had considered his behavior frivolous. It wasn’t, of course. That‘s normal behavior on a set, keep it light and relaxed until the camera rolls. Paul had never worked in a QM production since that time. Barry Cahill was cast to play the bus driver.

THE FUGITIVE, like so many of the programs of the early sixties, provided wonderful roles for women. ROUTE 66, NAKED CITY, DR. KILDARE, BEN CASEY, BREAKING POINT – none of them had a woman as the star of the series, but the guest star roles for the ladies were interesting and diverse. What we didn’t know then was that this was going to be changing and in the not too distant future.

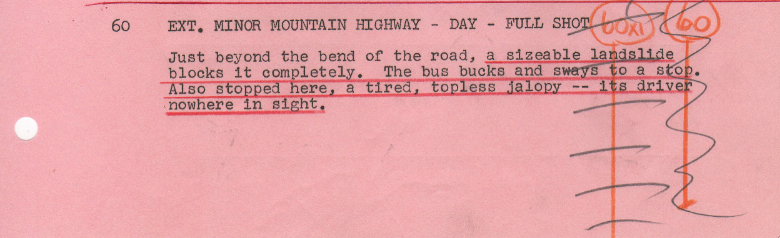

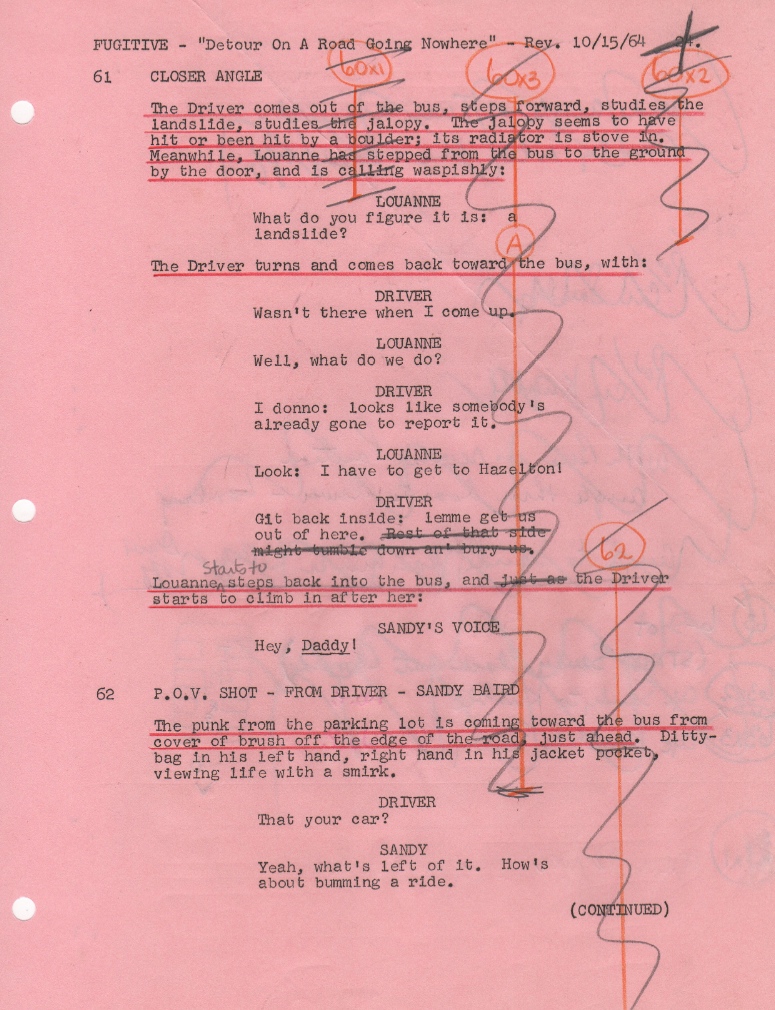

The script called for a landslide blocking the mountain road.

Obviously there was no way that time and budget would allow for the building of a landslide blocking the canyon road and the time and budget that would be required to clear the debris after filming. Remember Frayne Williams’ “sublimation of limitations”? We just angled the bus so we could shoot into the side of the canyon bordering the road. Then with judicious camera angles the standing hillsides stood in for the roadway impediment.

Quinn Martin had another standing format rule for his productions, a rule that I sometimes found annoying and restrictive: before an interior scene there had to be an establishing shot of the building in which the scene was taking place.

Rear screen process photography had been developed by the major film studios so that production could be completed without leaving the lot. But by the sixties more adventuresome independent productions were being filmed, and some of the old methods of film production were being replaced. This also applied to television. 0n ROUTE 66 I had for the first time filmed a moving car scene by towing it. On NAKED CITY I had filmed moving car scenes with the camera in the car. I mention all of this because Quinn Martin had another strict production policy: all such sequences had to be filmed in process.

All of the scenes in the interior of the moving bus were filmed the final day at the studio. We did not film them in the actual bus; rather a mock-up set of a bus was used. That was a bus whose side walls could be removed to facilitate getting the required camera angles. When I wrote about filming METAMORPHOSIS on STAR TREK, I described how we coped with having one limited cyclorama for the sky and could only shoot in one direction. The same thing applied to filming in process. There was only one process screen behind the bus on which the moving image of passing scenery was projected. But that moving image had to change. If we were looking straight back in the bus, the image was of road pulling away, exactly as if you looked out of the rear window of a real moving bus. If you looked out the side window of a moving bus, the movement was different from what you would see if you looked out the window of the opposite side of the bus. Since the process screen didn’t move, that meant the bus set had to move. What I’m trying to point out is that repositioning the bus set and relighting it was a time consuming procedure. So to simplify that, all the setups for all the sequences in any one of the three angles would be filmed at the same time. First all the angles in the sequences shooting straight back in the bus would be filmed, then all the angles looking to the right side of the bus and finally all of the angles looking to the left side of the bus. The bus would be turned, bus walls would be removed as it was set up in front of the process screen and all of the angles in that direction from all of the scenes would be filmed. Then the other side of the bus would be set up and the same procedure would be followed. There were eight pages to be filmed in process. This was no major problem for me. I planned my coverage and could work my way through my shot list. It’s the actors who should be commended. They could be working in five or six different sequences at the same time.

To further complicate matters, the final sequence in the moving bus was night, which required different lighting.

The decision to film the sequences after the bus broke down in a green set had me concerned. I had never filmed in one before and I was fearful that it would look fake. In my naive inexperience I would have preferred to shoot it in the canyon where the bus broke down. But those sequences added up to over thirty-one pages. That would have meant filming from dusk to dawn. Fine for a feature film where three or four pages a night would have been acceptable. But this was television. By creating a wooded set on the stage we filmed the thirty-one pages in less than two and a half days.

From the beginning I was aware that the script, once the bus broke down, was comprised of short isolated disconnected scenes. To prevent the presentation from being too choppy, I determined to connect the scenes by having a character involved in an ensuing scene witness the preceding scene.

And what an interesting twist in character the script provided. Usually people wanted to help Kimble because they recognized his innate decency and believed in his innocence. Sandy decided he wanted to help him because he believed he was guilty.

There are times when directors are working that are transformational. I remember so vividly that in 1956 when I was doing my homework blocking the staging for a theatre production of DEATH OF A SALESMAN, my feeling scene after scene of an inner growth, of a reaching out for something beyond moving the actors around on the stage. I had such a revelation on the set when staging a scene between Kimble and Louanne. I had not preplanned it, but I suddenly saw a way to add a dimension to the scene by involving a third character overhearing what was transpiring.

One of the warnings from ABC Continuity Acceptance:

In scene 126 when Langner backhands Kimble (and Kimble’s hands are tied) please be sure that Langner does not hit him more than once.

I didn’t feel it was necessary to slap him even once. As for the fall that Kimble took when Langner shoved him, that was done by David’s stunt double. We couldn’t risk David doing that with his hands tied behind his back. That’s what stunt men are for.

The other warning from continuity acceptance had been:

In scenes 146 & 148, please make sure that Louanne does not whisper in Langner’s ear. She can glance at him provocatively, comport herself sexily, but please no whispers

My those network minds! Lewd whispering! Double backhand slaps! Come on, guys (and gals). Stop fantasizing.

I won’t even honor with an acknowledgement the third warning from Continuity Acceptance that the young boy not hold the knife to anyone’s throat. I wonder if television today has arrived at its current level because finally directors rebelled and started doing all of the things Continuity Acceptance told them not to do.

Quinn Martin instituted a format for his first independent production, THE NEW BREED. He started with a climactic scene as a teaser followed by the show’s billboard, then four acts and an epilog. That was the format he used for all of his successful series that followed.

The journey continues

This is not one of my favorite episodes of this series. Lee Bowman’s character got on my nerves from start to finish…just pathetic and annoying (or is my reaction the proof of good casting?!). Kimble’s method of escape didn’t dazzle me when compared to other eps.

When I first saw this episode on a local PBS TV station in the late ‘80s, I was taken aback by a line in the closing credits: Lana Wood…..The Doll. Okay, I know political correctness and women’s lib didn’t exist in ’64, but really…The Doll?! I guess Lana and her agent didn’t know or care.

I wonder if Quinn Martin’s “don’t use” list had a lot of women on it, because the ones he used on ‘The Fugitive’ came back time and again: Elizabeth Allen (3 times), Lois Nettleton (3 times), Antoinette Bower (3 times), Joanna Moore (3 times), Carol Rossen (5 times).

Ralph, did you ever meet Phyllis Thaxter’s ex-husband Jim Aubrey (nicknamed ‘The Smiling Cobra’ by John Houseman) during your days at CBS or later?

First off, let’s check off your reaction to Lee Bowman as good casting.

I don’t think the reappearance of the actresses you mentioned indicated a “don’t use” list” for Quinn as much as the fact that performers he liked could count on an appearance a year on any or all of his shows in production. I never had any direct contact with Quinn regarding casting. The casting director and I would submit our requests to John Conwell, who would then submit them to Quinn for approval. Very seldom did he deny my request. Once on A QUESTION OF INNOCENCE on THE FBI he asked that I switch the roles on the two actors I requested (Andrew Duggan and Larry Gates) and on my last BARNABY JONES I requested Beulah Bondi and Quinn said he would love to have Miss Bondi guest star on a show, but he felt she was too old for the one I was casting. Phyllis Thaxter played it. And finally, no, I never met or discussed Mr. Aubrey with Phyllis.

I really love the TV series, “The Fugitive”. I’ve watched it off and on for many years. Right now I’ve been watching it on youtube in sequence and also through the local library that has some of the DVD’s. I really like the first three seasons, all in B&W. The fourth season they went to color and although I liked the intro……..”The Fugitive, in color” I felt the series was not as good that last year. Loved all four episodes that you were involved with. There were so many actors and actresses involved with this show that went onto greater things.

Thanks for letting us view an actual page of a script! And an inter-office memo. Wow, duly impressed. I never thought of a stunt man before for David Janssen; but his knees would have been blown out surely by the second season…. by the way, Chevy Chase in Wheeling is still a lovely venue for receptions and golf. We lived about 20 miles from there and in the 1960’s my Dad had a small construction job on site, so ‘us kids’ got to tag along. Thanks for your insights on The Fugitive! Adrienne

How come in all of the write ups on this episode no one ever mentions the leg shot Louann gives Langner. There were many shows that Elizabeth Allen guested on that almost always focused on her legs. They must have been gorgeous.

Maybe because it was thought her leg spoke for itself!

I might be able to shed some light on “the thing about knives,” not from a film production standpoint but from a human standpoint. For many years I volunteered at Gettysburg National Military Park, where on Day 2 of the battle there was a very famous bayonet charge by the 20th Maine down Little Round Top (see the film Gettysburg if you want to check it out). What I’m saying is not part of any film, and I’m not sure you’ll find it discussed in too many history books, but some historians believe there is something primeval that happens to a person when they see something sharp coming at them. During the Civil War, men would march into hails of bullets and cannon fire, but run like crazy from a bayonet charge. Something about sharp pointed things coming at them would trigger an ancient knee-jerk reaction. At Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, the Confederates ran uphill into rifle fire over and over, but when the 20th Maine ran out of bullets and went for a bayonet charge, the Confederates turned and ran. THAT’s the thing about knives, I think. It’s ancient, hidden deep in our reflexes, to be frightened of those sharp pointed things.

Thank you Marleen. I love when added info is added to the conversation.

Dear Mr. Senensky:

When did Quinn Martin switch away from using process shots? THE STREETS OF SAN FRANCISCO (1972-1977) never used them.

I think it was STREETS!