In 1948, my second year as a directing major at the Pasadena Playhouse College of Theatre Arts, I directed two productions in the Balcony theatres. In the 14 following years leading to JOHNNY TEMPLE, my first television film, I directed 40 more theatre productions – in Mason City, Iowa, Hollywood, Florida, Des Moines, Iowa and finally Southern California in West Hollywood, Pasadena, Los Angeles, Santa Monica, Beverly Hills and Westwood. I directed productions on large proscenium stages and smaller proscenium stages; in a large tent for theatre-in-the-round, and in a small 99-seat theatre with the audience seated on all four sides of the playing area and some others with the audience on three sides. Each of those productions was a learning experience. But one stands out in my memory at the head of the list. Let me tell you about that production.

At the beginning of 1956, 15 months after my return to Southern California, I was functioning evenings (daytime, of course, I was employed working as a typist in CBS’s Radio division mimeo department, cutting and printing stencils for their radio shows) at the Morgan Theatre in Santa Monica as producer for their production of DETECTIVE STORY. The theatre was a local community project of the Santa Monica Theatre Guild, staffed by many volunteers from the film industry and a site where aspiring film actors competed to perform. I wanted to direct there. Those at the theatre knew of my background and desire to direct. Functioning as a producer for one of their productions was my opening gambit.

Sometime in the spring, a couple of months later, I received a phone call from Grace Godino, Vice-President of the Santa Monica Theatre Guild. Grace worked at the Walt Disney studios as an inker and as an occasional stand-in for Rita Hayworth. Grace was excited. She told me their next production was to be Somerset Maugham’s RAIN, the ribald story of Sadie Thompson that started as a short story, was then developed into a 1922 stage play with Jeanne Eagels playing Sadie, then on to the silver screen with Gloria Swanson in the 1928 silent version (SADIE THOMPSON), Joan Crawford in the 1932 talkie (RAIN), and Rita Hayworth in the 1953 color version (MISS SADIE THOMPSON). Grace told me there were great plans for the production. For the set the large double doors in the upstage wall of the stage were going to be opened, the set would be extended beyond the theatre wall, there would be REAL RAIN pouring down, and they wanted me to direct it. I was pleased with the invitation, less so with the project, even with real rain, so I thanked her for the offer but turned it down. That spring, continuing my employment seated at an electric typewriter in CBS’s Hollywood quarters at Sunset and Gower, I returned to Gilmor Brown’s Playbox in Pasadena to direct a production of ENGAGED, a Gilbert and Sullivan play without music.

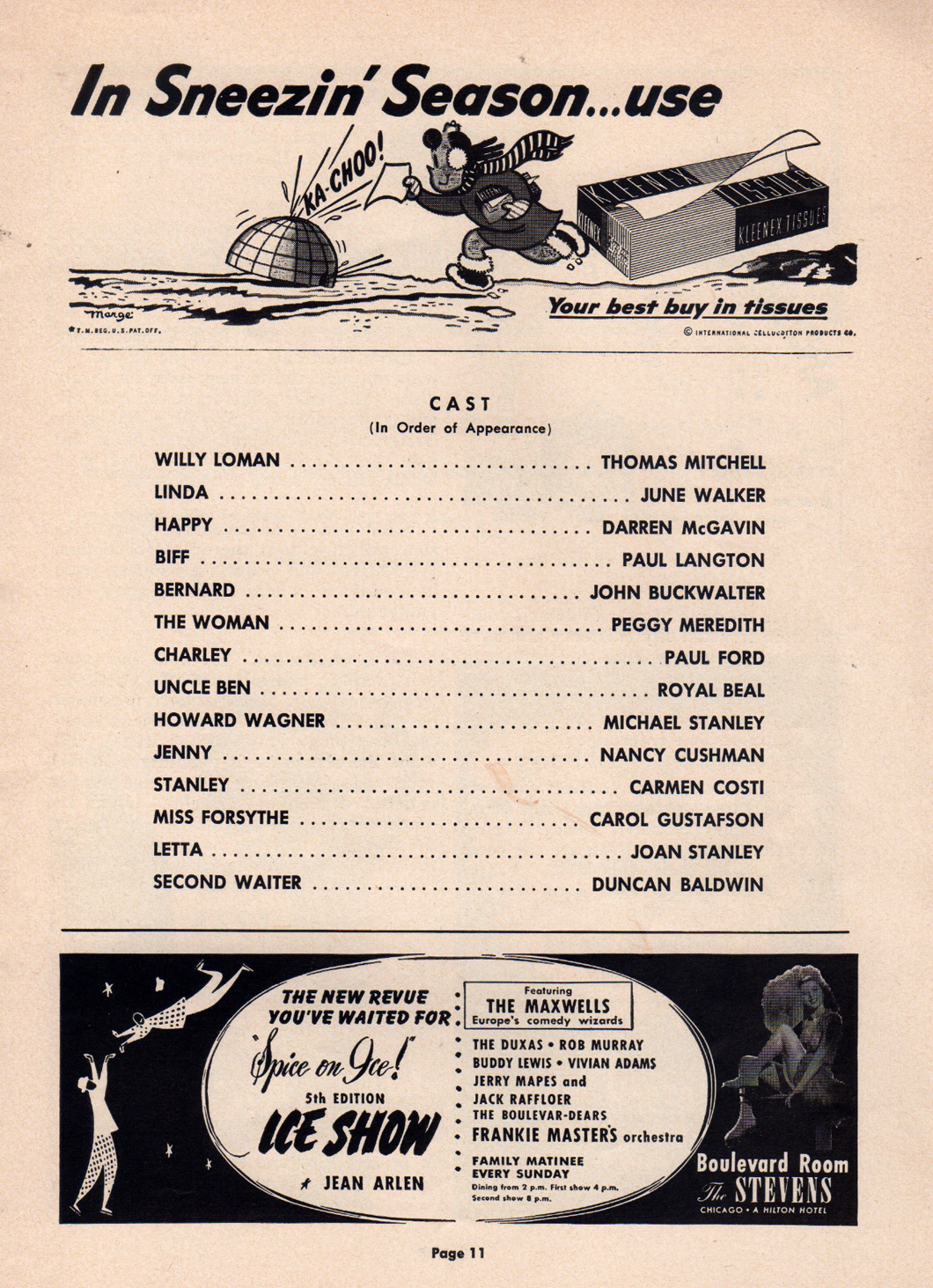

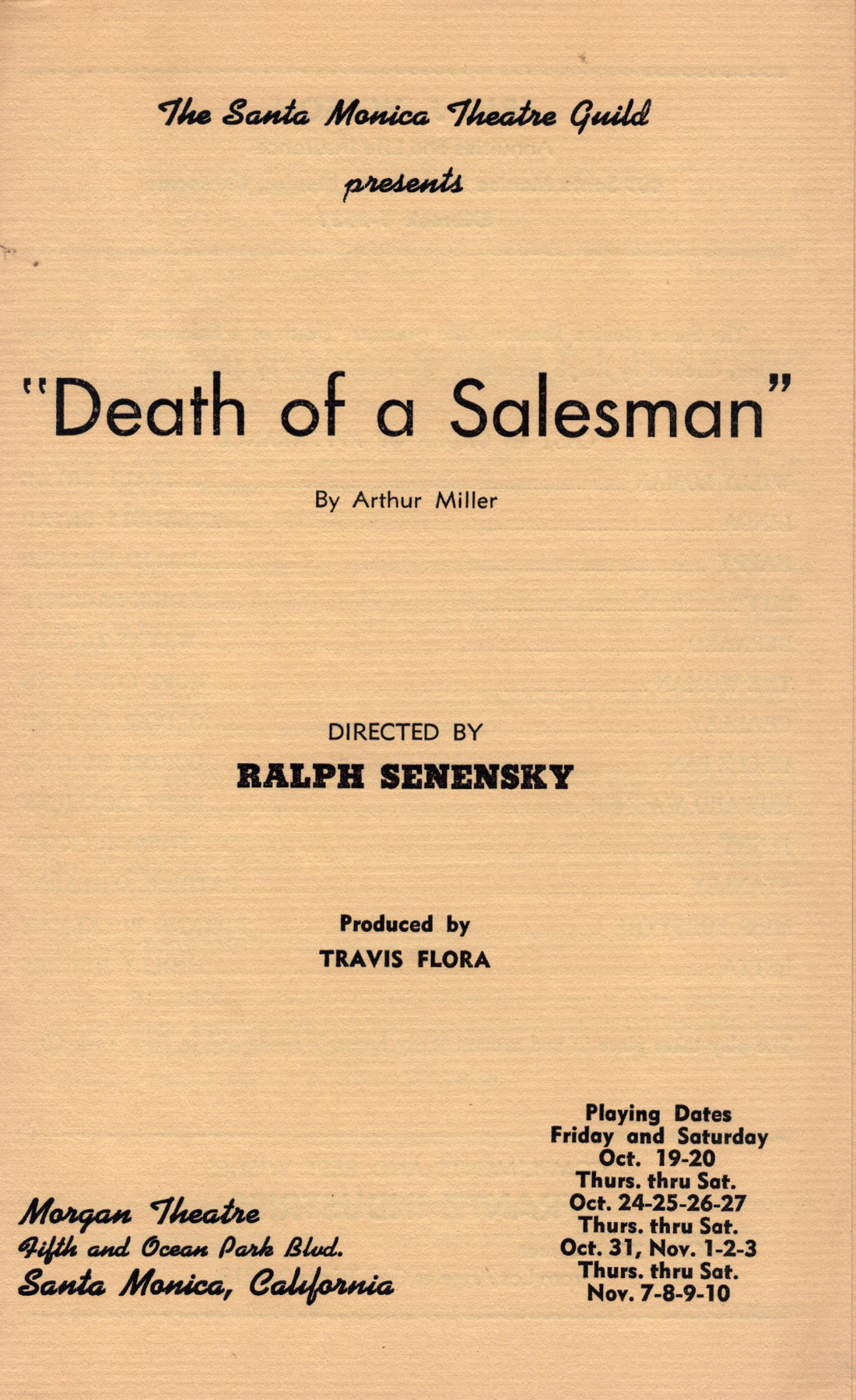

Early that summer I received another phone call from Grace with an invitation to direct that I immediately accepted. The play: Arthur Miller’s DEATH OF A SALESMAN. Six years earlier I had seen in Chicago the National Touring Company production starring Thomas Mitchell.

Notice the price of tickets above on the Stagebills.

Notice the price of tickets above on the Stagebills.

More about that production later

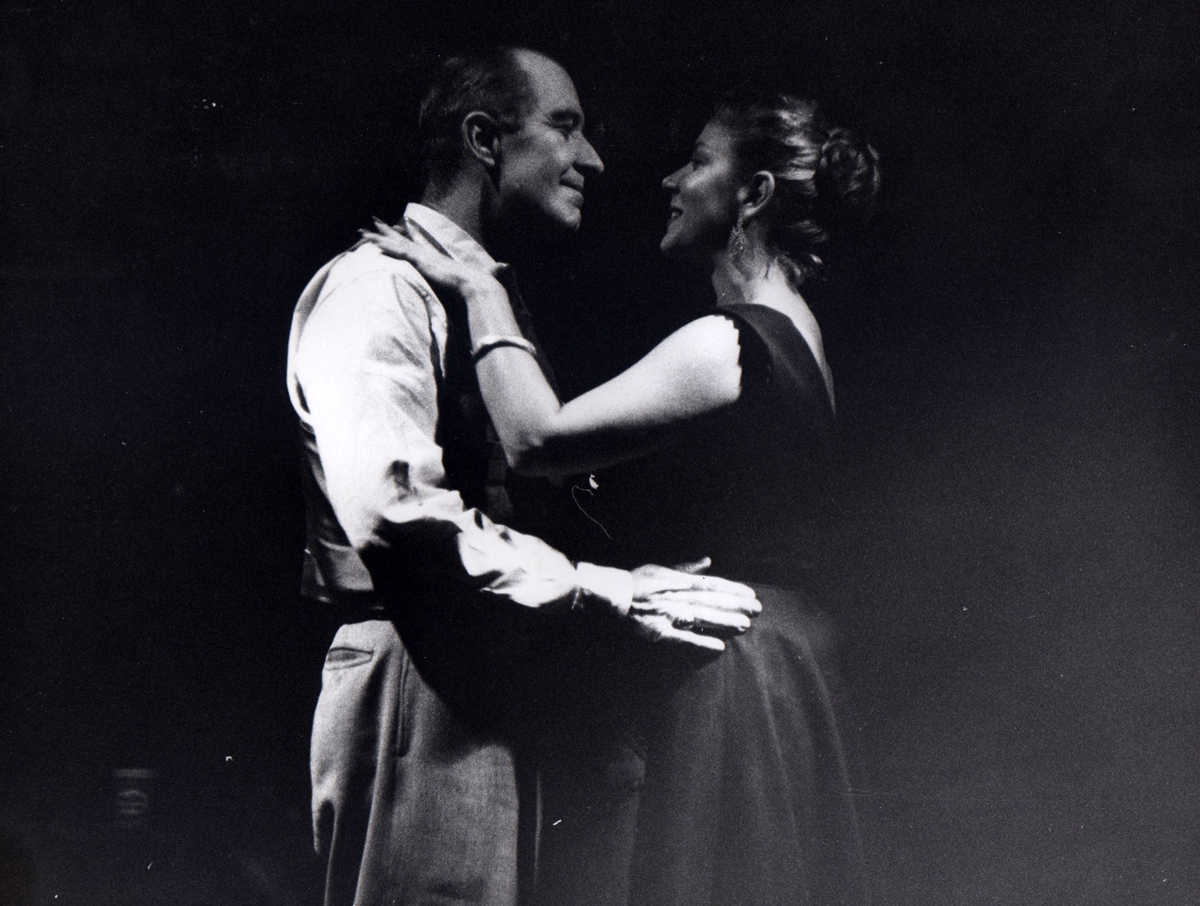

I knew immediately who would be playing two of the leading roles. A year and a half earlier I had met Paul and Claudia Bryar (whom I knew as Gaby and Hort [for Hortense] Barrere) when I cast them in MY THREE ANGELS at the Players Ring Theatre. They of course for appearance sake would have to come and audition, but they were going to be my Willy and Linda Loman.

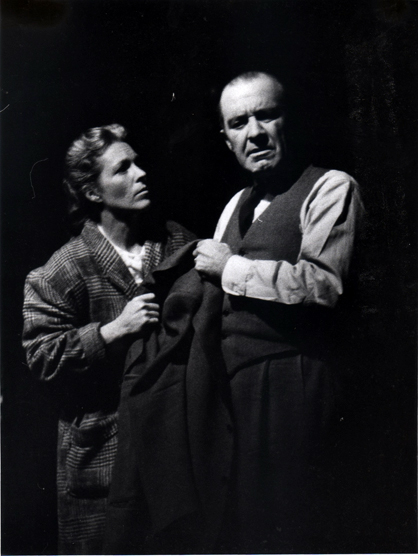

Claudia Bryar (Linda) and Paul Bryar (Willy)

Claudia Bryar (Linda) and Paul Bryar (Willy)

The Morgan Theatre at 5th and Ocean Park in Santa Monica had a proscenium stage less wide than the main stage at the Pasadena Playhouse; it had no fly space, and the depth of the stage was prohibitively limited. The audience seating was raked, had a little over 100 seats, or possibly a few less. It was a charmer. Five years later when I was on staff at MGM as the assistant to the producer on a new television series, DR. KILDARE, our 3rd show to be filmed, SHINING IMAGE, had its opening scene in a small theatre. I told our location people about the Morgan, and that’s where the scene was filmed. So you can get a glimpse of the theatre auditorium, here’s a clip from that scene directed by Buzz Kulik with guest star Suzanne Pleshette.

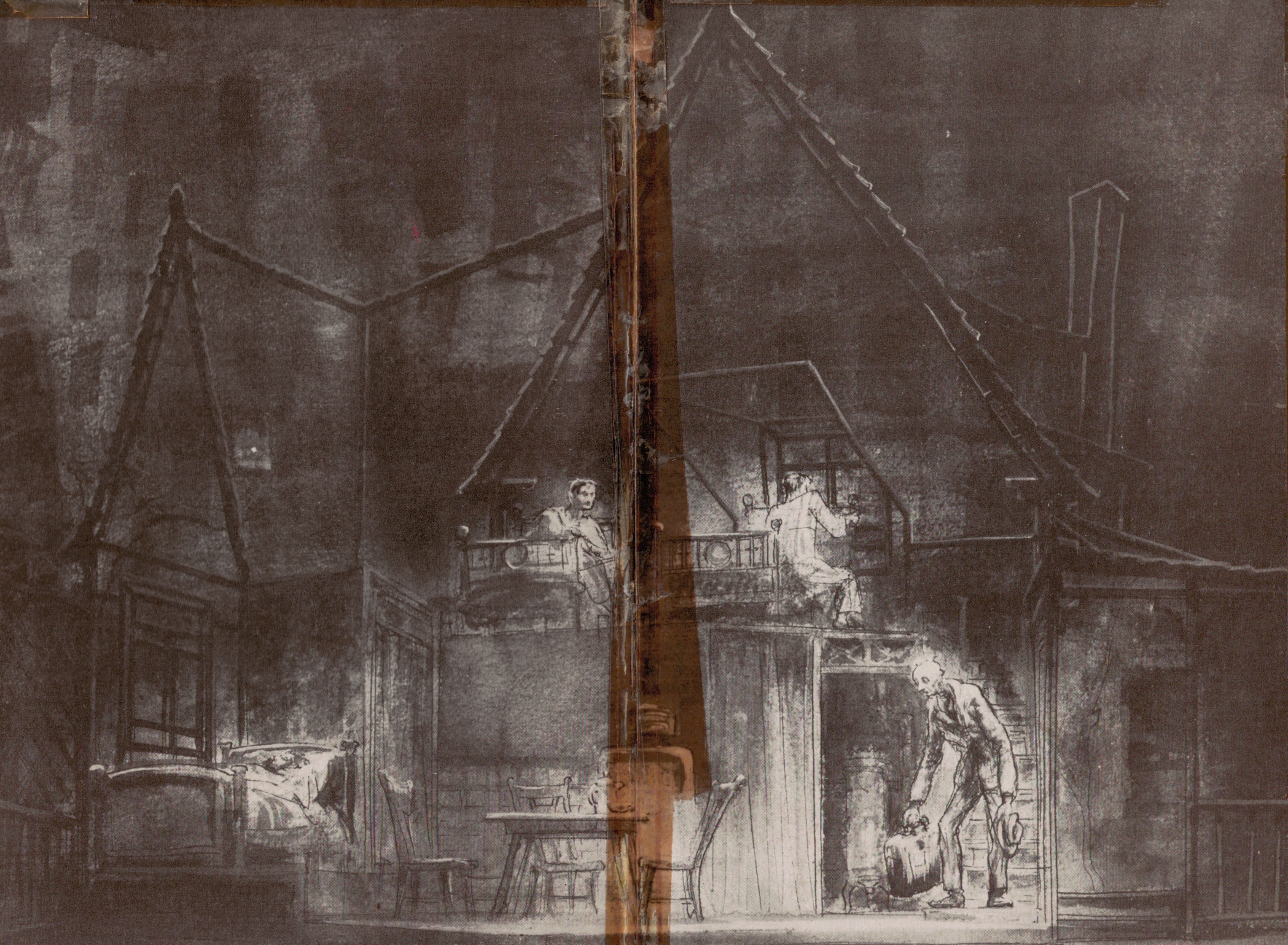

DEATH OF A SALESMAN was unlike any play I had directed. The scenes of the 2 acts took place both in the kitchen and 2 bedrooms of the Loman home and outside of the house, in 2 separate offices, a hotel room, a restaurant, a restroom and a cemetery. The play had a breakdown of time and space as the characters moved in and out between the present and the past; the flow of action had to be continuous, like a movie. Jo Mielziner’s set for the original 1949 Broadway production provided the setting for this flow of action to occur.

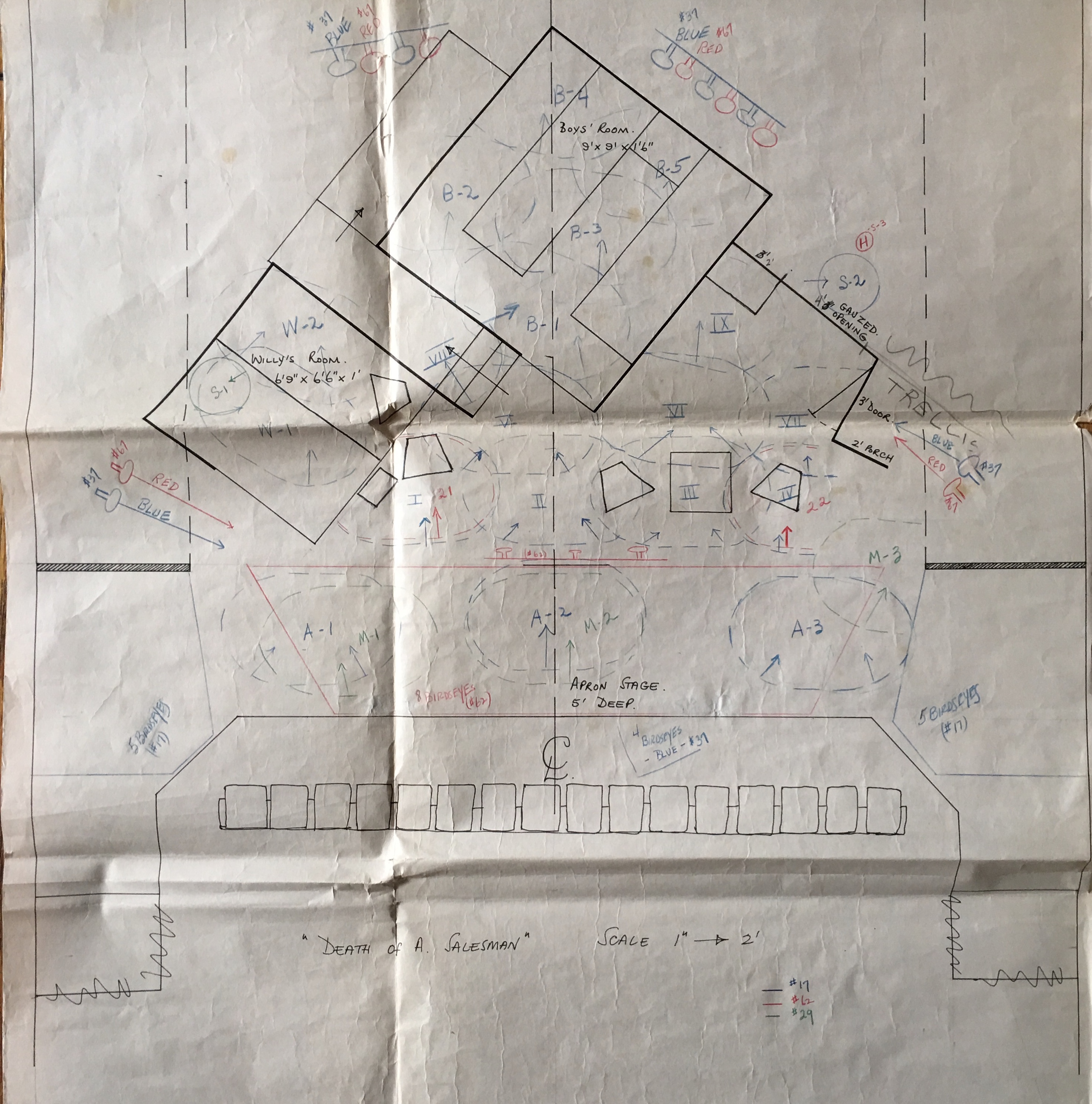

I liked his arrangement of the 2 bedrooms and kitchen and the various elevations for those playing areas, but I knew with the width, depth and lack of fly space of our stage we could never duplicate it, and then Ruth Sofaer entered. I don’t remember how we met, but Ruth was the daughter of the English actor, Abraham Sofaer, and a very talented scenic artist. She designed a floor plan of the interior of the house to be backed by black drapes with the other locations being played on the 5-foot deep stage apron.

She then added structural doorways and windows that the very limited height of our stage permitted. But the designing work wasn’t completed. Ruth made a scale drawing of the stage. She then made scale drawn cutouts of the 2 bedrooms and the corridor connecting them. We laid the cutouts on the floor plan for the stage, and they were too large. We trimmed and trimmed again until they fit. Volunteers at the theatre built the bedroom risers. The smaller bedroom and corridor were 18 inches high; the larger boys’ bedroom was 6 inches higher. I remember the weekend we installed the set. The upstage corner of the boys’ bedroom was to be ½ an inch from the back wall. I remember I felt there was not enough space for actors’ crossovers behind the set. A few more inches shouldn’t make a difference! I had that riser moved downstage just an additional inch and a half. Big mistake! With all of the set components also moving the set didn’t fit. So we moved everything back to where Ruth had planned.

My cast of 13 actors included the professional aforementioned Bryars and Dick Sargent playing their son, Biff. The other 10 were either aspiring actors, still without their professional guild card or community theatre aspirants. With those in the latter group, my 4 years experience directing community theatre in the midwest, had me confident and totally comfortable, but I was still adjusting to directing experienced actors. Having said that, with the Bryars I had a distinct double advantage, I had directed them a year and a half earlier in MY THREE ANGELS, and in the ensuing time we had become very close friends. Claudia was still in the early stages of her film career, but Paul had been working in the film industry for 18 years. He was a wonderful source of advice and encouragement.

Another factor making this unlike my previous directing experiences was the script of DEATH OF A SALESMAN. Arthur Miller, as in all of his plays, dealt with social values. Like his contemporary, Tennessee Williams, he had his characters speak dialog beyond realism, ascending to the poetic. I remember as I pre=planned my staging and playing of scenes in the play of feeling like I was being drawn up and into new, unexplored-for-me areas – territory of Greek tragedy dimensions. That would be my challenge – to accomplish that in that small set on that small stage .

Early in September we began our 6 weeks of rehearsal. I worked my daily shift at CBS, grabbed a quick meal and drove from Hollywood to the theatre in Santa Monica. The final two weeks before we opened I made arrangements at CBS to take my yearly vacation, so that I could devote full time and attention to the play. We opened on October 19th.

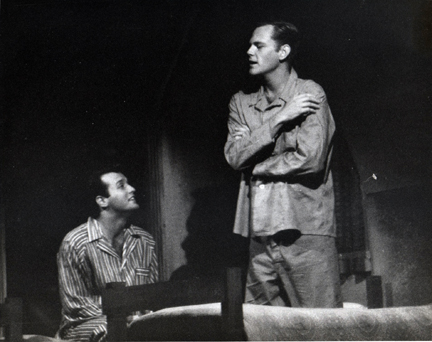

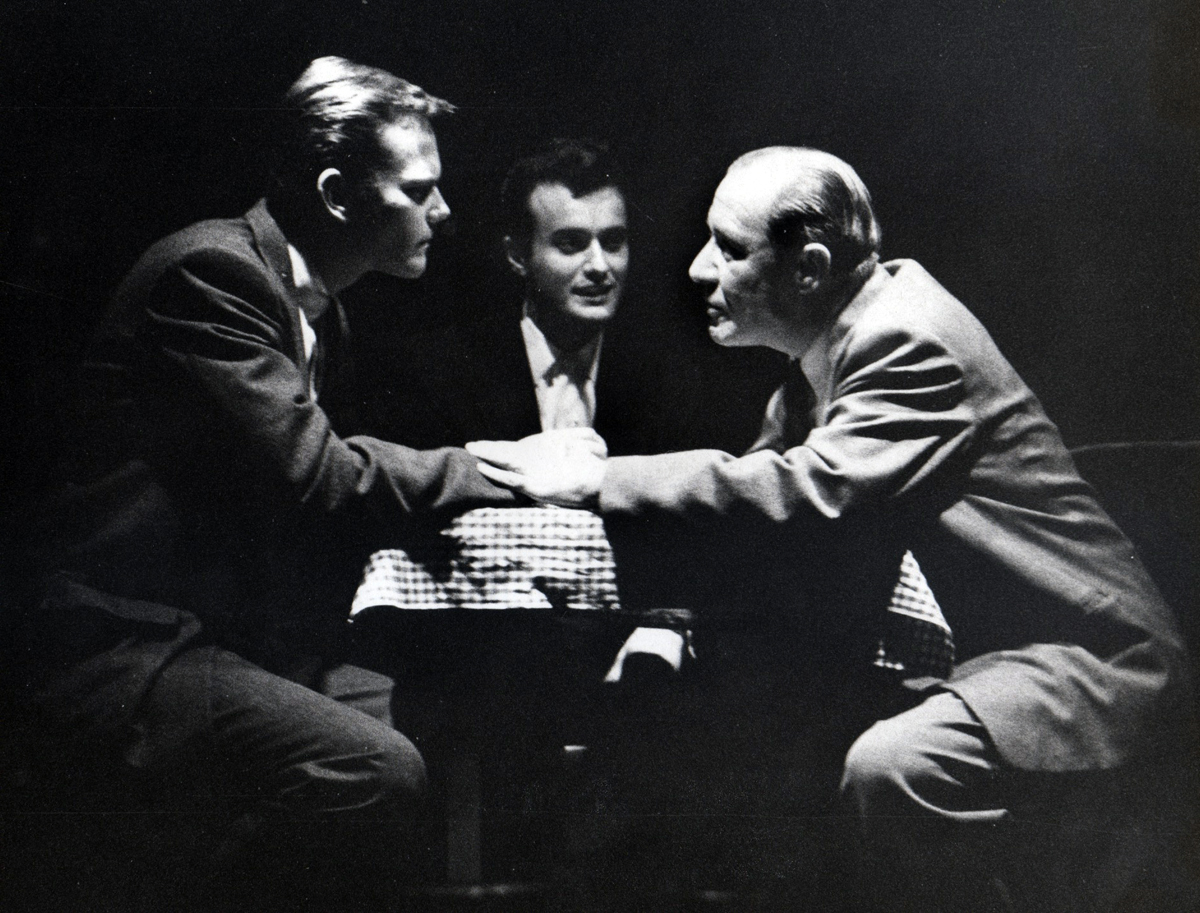

Thirty-four year old Biff has returned home again – still searching to find himself. He tries to convince his younger brother, Happy, to give up his current wastrel life and join him in a ranching venture.

David Kramer (Happy) and Dick Sargent (Biff)

David Kramer (Happy) and Dick Sargent (Biff)

Willy adores Biff. Although being disappointed at Biff’s lack of direction in his life, he constantly brags about how well Biff is doing, — alternately encouraging and berating him.

Dick Sargent (Biff), David Kramer (Happy) and Paul Bryar (Willy)

Dick Sargent (Biff), David Kramer (Happy) and Paul Bryar (Willy)

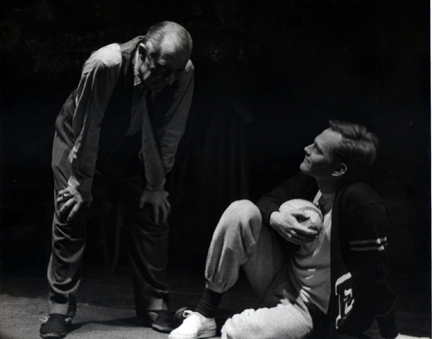

The play flashbacks to the past when Biff and Happy were teenagers…

Paul Bryar (Willy) and Dick Sargent (Biff)

Paul Bryar (Willy) and Dick Sargent (Biff)

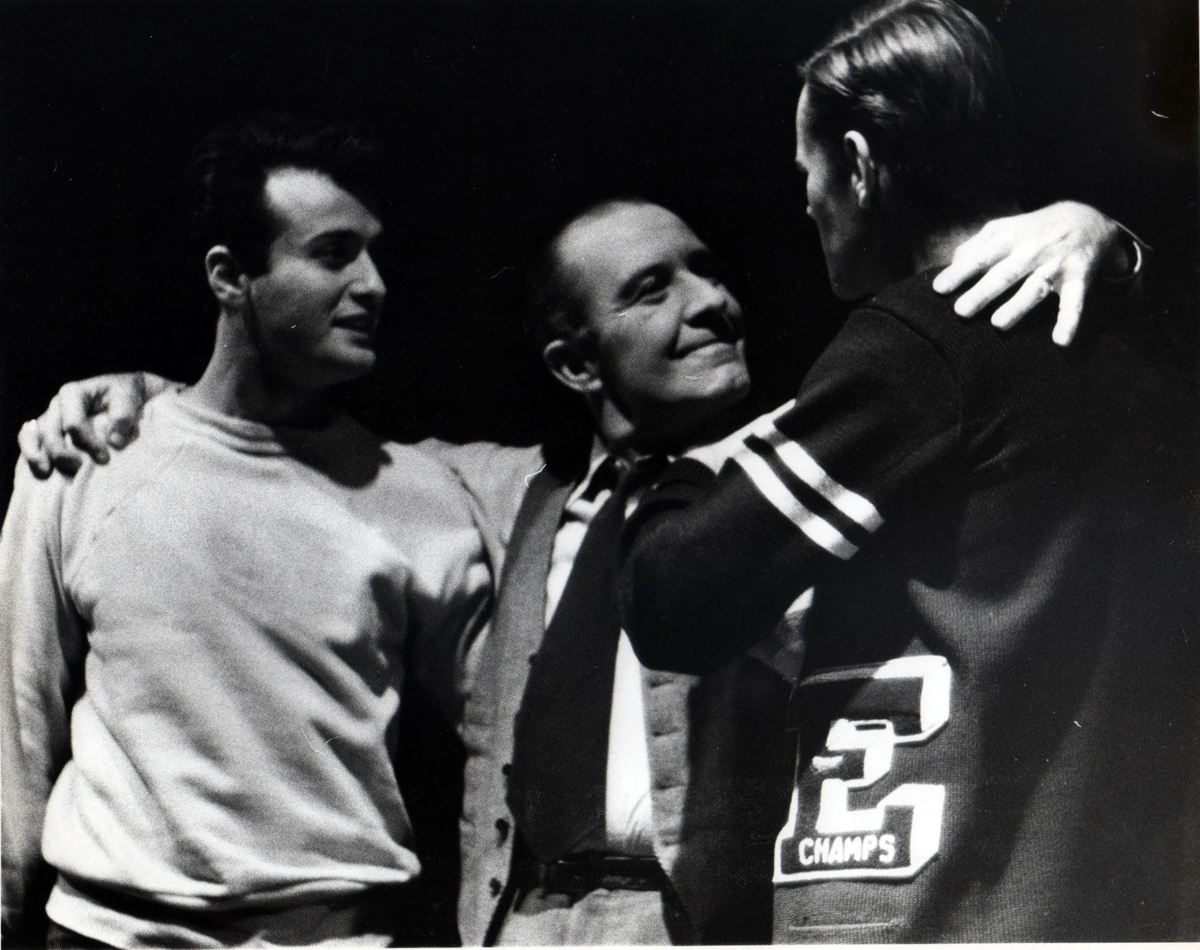

David Kramer (Happy), Paul Bryar (Willy) and Dick Sargent (Biff)

David Kramer (Happy), Paul Bryar (Willy) and Dick Sargent (Biff)

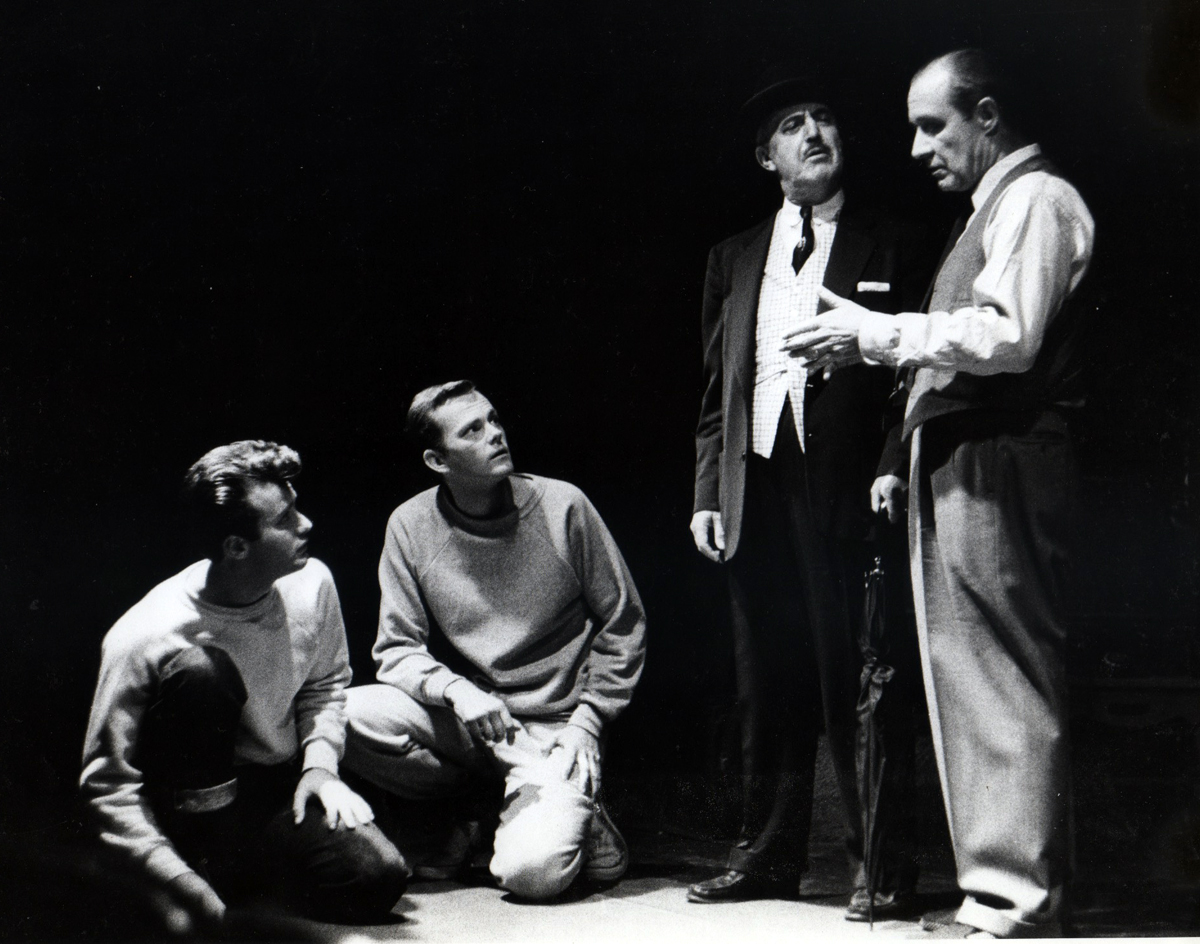

… when often Willy’s older brother Ben keeps returning, proclaiming, “When I went into the jungle, I was 17. When I walked out I was 21. And, by God, I was rich.”

David Kramer (Happy) Dick Sargent (Bilff) Jerome Burton (Ben) and Paul Bryar (Willy)

David Kramer (Happy) Dick Sargent (Bilff) Jerome Burton (Ben) and Paul Bryar (Willy)

Willy’s dream. But now he is depending on Charley, his neighbor and friend, for weekly ‘loans’ to survive.

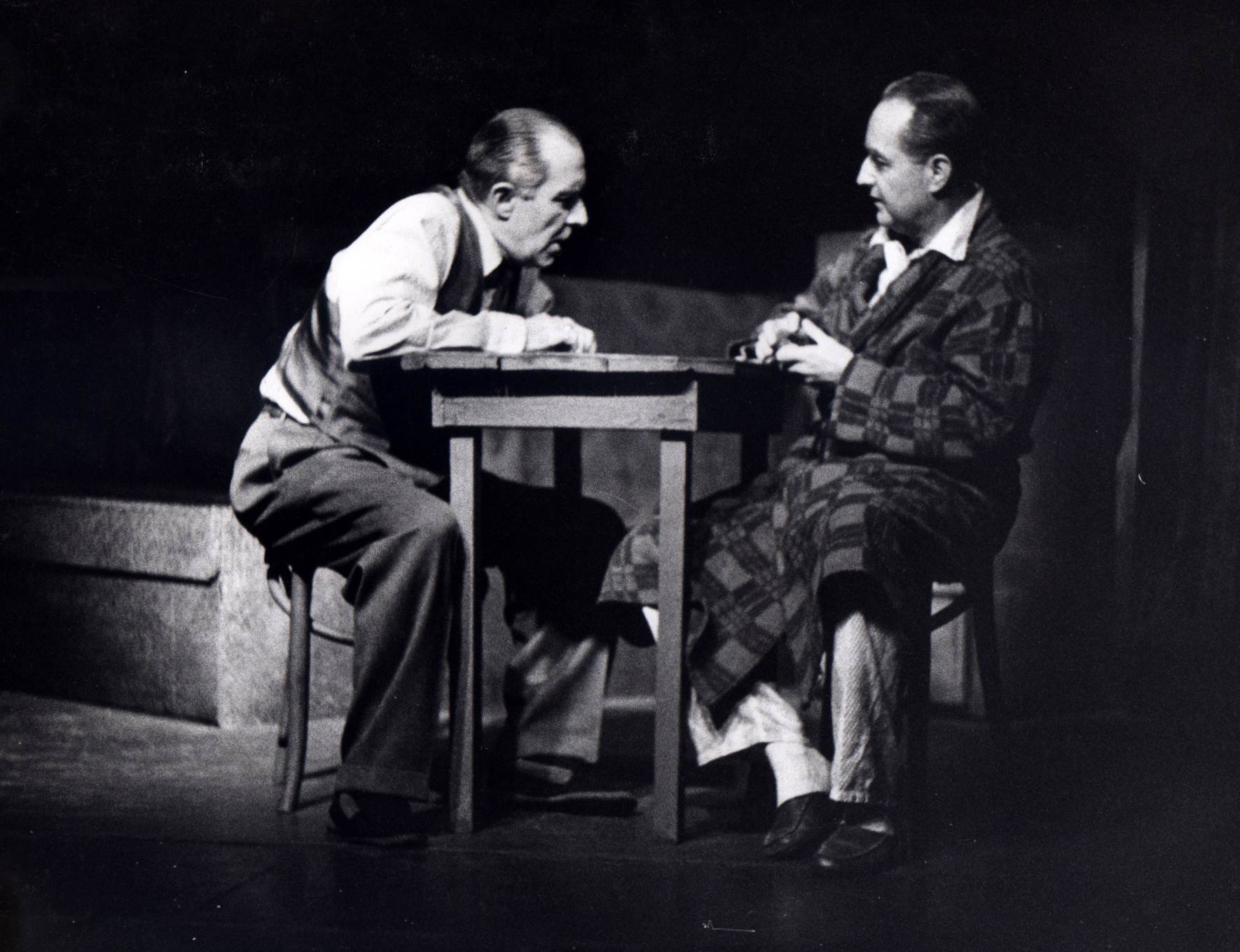

Paul Bryar (Willy) and Oliver Fowler (Charley)

When I saw the Chicago production, in an evening of overpowering scenes there were two that stood out:

Willy goes to Charley’s office for his weekly ’check’. While waiting to see Charley, Bernard, Charley’s son, comes in. Bernard is the same age as Biff. We have seen `him as a teenager in the flashbacks. Willy has always looked down on Bernard. He doesn’t measure up to his boys. When Bernard offers Willy a cigarette, instead of a cigarette Willy takes the cigarette case. It is solid gold. He stares at it and then at Bernard. His opinion of Bernard changes because he owns a gold cigarette case. That to him is SUCCESS!

That bit of business is not in the printed play version. I wonder if it was in the Broadway production. Elia Kazan, who had directed the Broadway SALESMAN, just produced the touring company. Harold Clurman directed it. I think that wonderful bit came from Thomas Mitchell.

The other outstanding scene:

The boys take Willy to dinner. Willy wants to hear about Biff’s important job interview that day. It was not successful. An argument begins, and Biff’s anger at his father can no longer be controlled. Suddenly we are in a hotel room…

Paul Bryar (Willy) and Hope Copeland (The Woman)

,,,and Biff appears — a surprise visit to his father on the road. A violent argument! Biff storms out leaving Willy on his knees, pounding the floor, demanding he come back. A waiter appears. We are back in the present. Willy is in the men’s restroom of the restaurant.

Both of those powerful sequences were in my production.

And the following powerful scene, when sobbing Biff pleads with Willy to understand, he, Biff, is not a great man, he’s a dollar an hour worker, and he clings to his father as he pleads with him to let go of him. As he runs off, Willy says, “Isn’t that remarkable. Biff – he likes me.” and Linda says, “He loves you, Willy.”

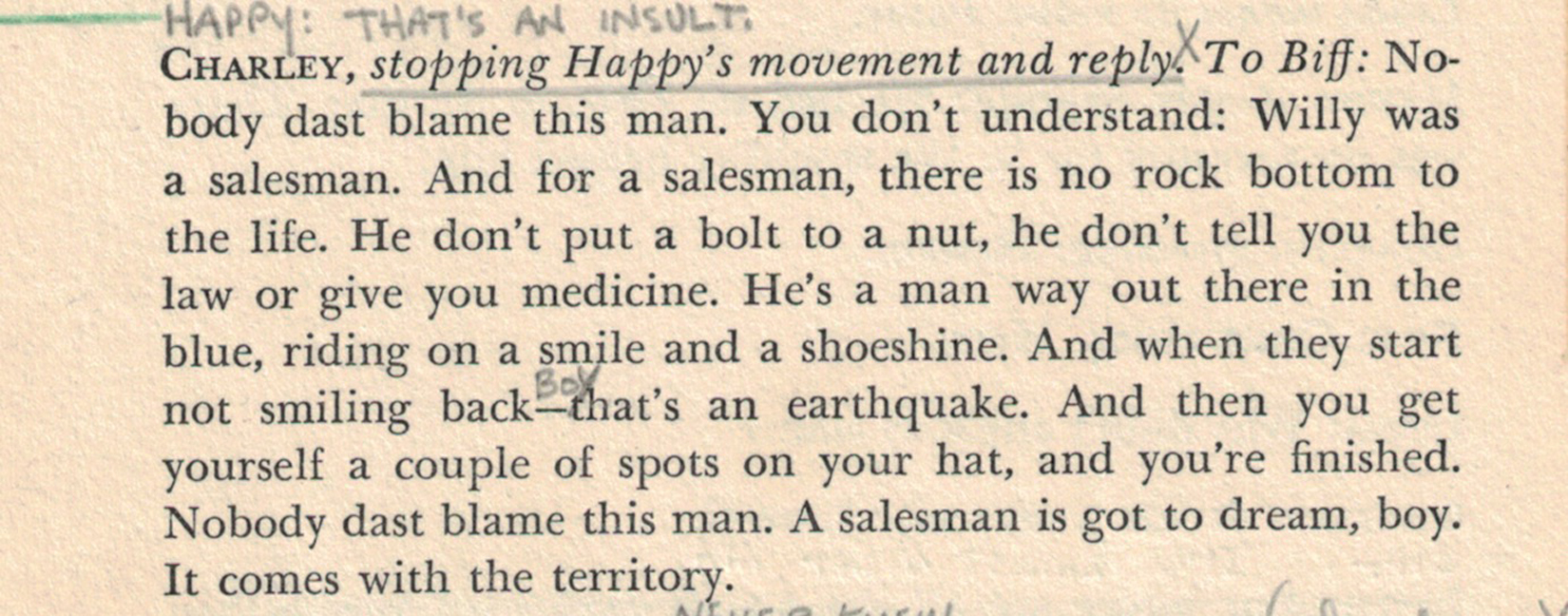

Arthur Miller wrote a beautiful summation of being a salesman, delivered by Charley at Willy’s funeral.

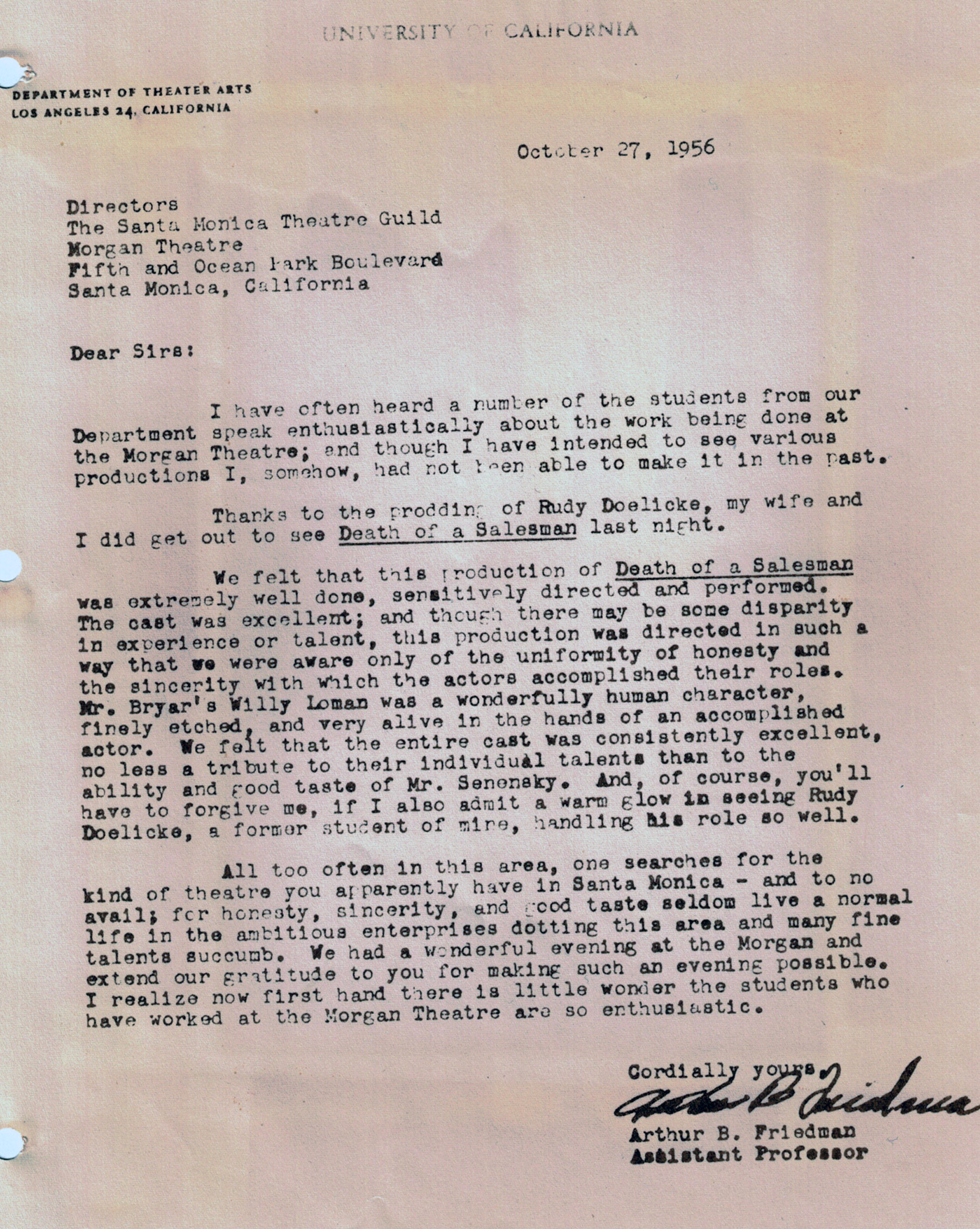

I did not know until I received a copy of a letter to the theatre from a professor in the Department of Theater Arts at UCLA that Rudy Doelicke, a member of my cast, was a former student at UCLA. Rudy played Howard, Willy’s boss, in a powerful scene firing him from the job he’s held for 18 years.

Paul Bryar (Willy) and Rudy Doelicki (Howard)

Here’s the letter:

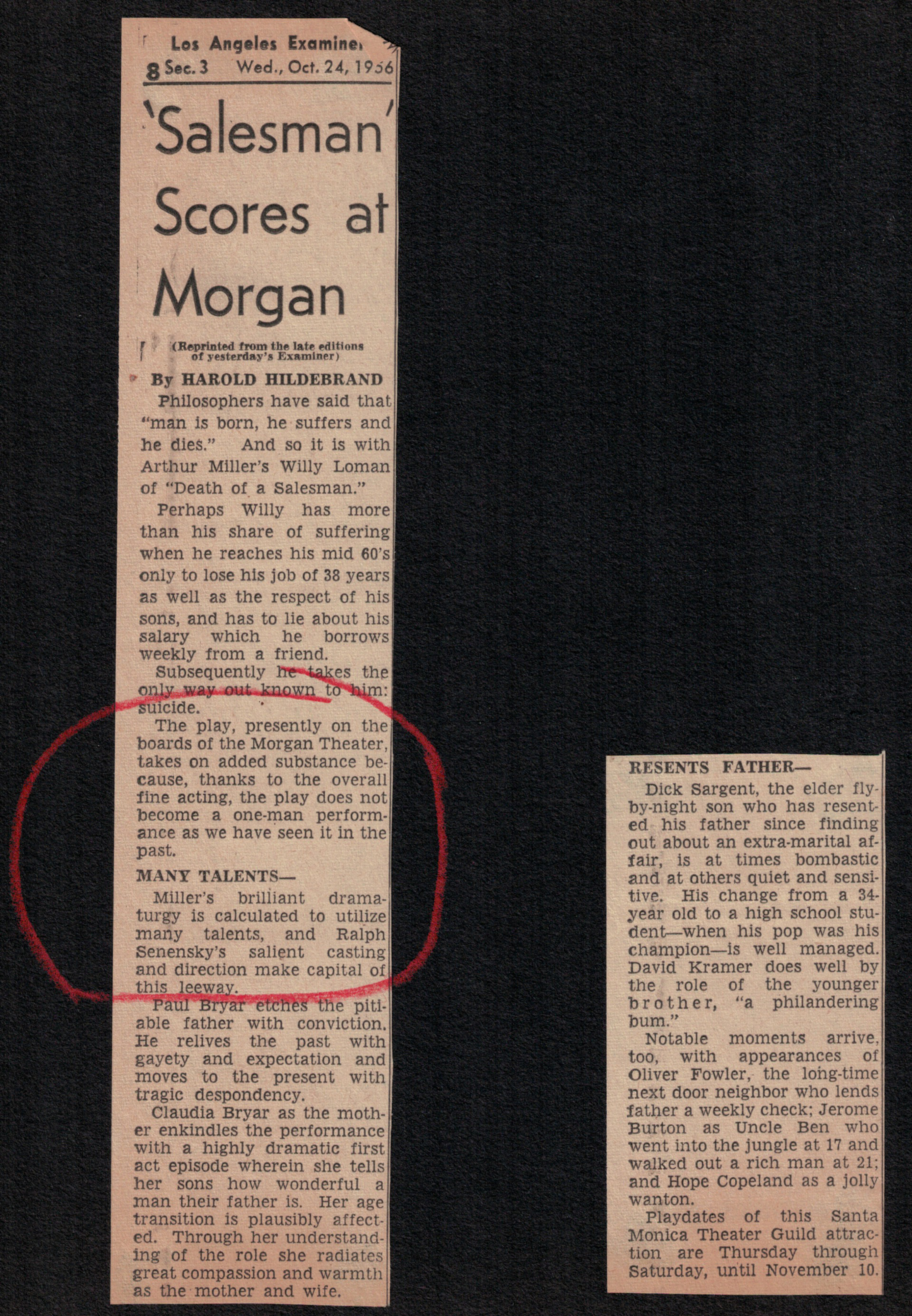

I could write the reviews were outstanding (they were), but instead you can read the one from the Los Angeles Examiner:

It grieves me that we did not have today’s digital cameras, so there could be an archival record of our production. I never got to work with Dick Sargent again, although I did get him cast in an episode of DR. KILDARE while I was on staff. Dick’s film career spanned 39 years. He is most remembered for his role of Darrin in the final 3 years of BEWITCHED when he replaced Dick York, who dropped out because of illness.

Paul and Claudia Bryar appeared more than often in my films, but I was never able to give them roles that matched Willy and Linda Loman. I came closest to doing that when I cast Claudia in THE FAMILY NOBODY WANTED. She played Woody Parfrey’s wife. They were a couple belonging to the church where a new minister has newly arrived with his wife and family of multi-racial children

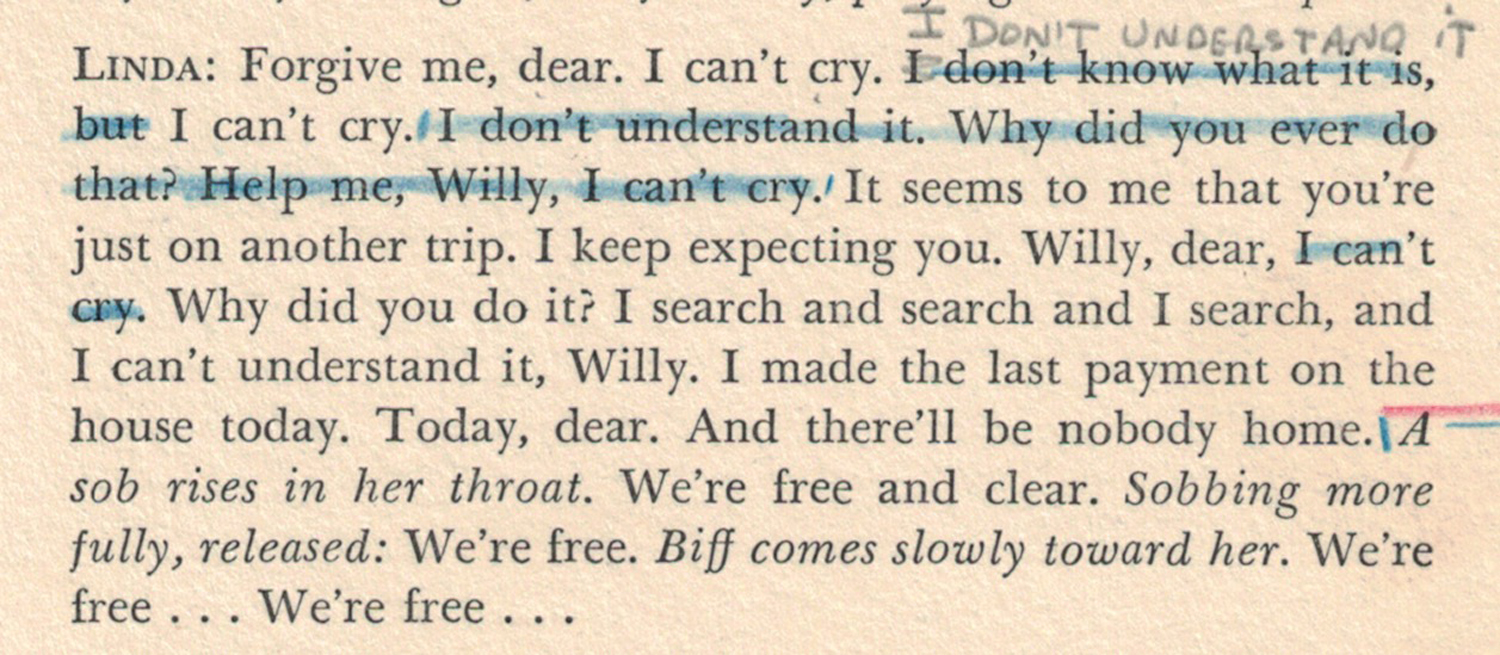

Many evenings during the run (and I attended every performance) I would stand in that aisle that Suzanne Pleshette ran down in the DR. KILDARE film clip, and during the final graveside scene when Linda delivered the play’s final speech ,,,

… I would hear audible sobs in the audience.

I think back to a decade before SALESMAN, when I was a student at the Pasadena Playhouse; to the small 45-seat East and West Balcony Theatres. Those were the theatres where the second-year students performed, where I had directed my 2 productions in my second year. The flats for the sets were gray; the wooden block furniture was gray. The purpose? The actor was being trained not to rely on stage sets, but that his or her performance must convey to the audience where the play was taking place. I took that to be training for directors as well.

I also remember Frayne Williams’ “Great art is a sublimation of limitations.”

My friend Judy Lewis came to see the production of SALESMAN. After the final curtain I took Judy up onto the set. As we stood in the kitchen area, Judy asked, “Where’s the tall stairway?”

“What tall stairway?” I asked.

“The one where Linda stood when she made that wonderful “attention must be paid” speech to her sons, scolding them for their behavior to their father”

I pointed to our 3 steps up 18-inches stairway.

Is it possible that Playhouse training had taken root?

Thank you for a look back at the early days of your directing.

I noticed names of two of the actors. Was that Darren McGavin of the television show, “Kolchak” and Paul Ford who played the colonel in the “Phil Silvers Show.”

It certainly was!

Mr Senensky – Hope that this note finds you Well and in Good Spirits! I’m just wondering if you are working on a New post ? I hope you are and look forward to reading it. All the Best , Take Care ☺

Indeed I am. I hope to get to it starting this coming Thursday!

…. 😊good ! Looking forward to it . Thank You.

I wish I could have seen this! “Death of a Salesman”, “The Glass Menagerie” and “All My Sons” are my three favorite plays. Thanks for the look back, and as always, thanks for sharing.