FILMED October 1971

From the emotional disturbance of construction worker James Whitmore in MY NAME IS MARTIN BURNHAM, to the problems attendant upon Season Hubley recovering her hearing in THE SOUND OF SUNLIGHT, Senensky seems always to have been interested in and particularly gifted in exploring the inner tensions and mental fears of the characters who populate the scripts he accepts.

Thus wrote Christopher Wicking and Tise Vahimagi in their 1979 book, THE AMERICAN VEIN, as they wrote about Directors and Directions in Television. However I question the last four words of their sentence: the scripts he accepts. As I have repeatedly pointed out, scripts were not submitted to directors directing episodic television for them to accept or reject; we were booked by dates. As for the scripts we were to direct, it was strictly a crapshoot. On rare occasions the script was sent to me a few days prior to the day I was to report; usually I received the script when I arrived at the studio, and happily for the first five years of my television-directing career, almost all of those scripts were sevens or elevens. But then there came a gradual change: many times a difficult four to shoot, and then the occasional pure snake eyes. I remember so many times sitting down with trepidation as I read the new assignment, only to discover with disappointment that again the script handed me was not populated by characters with genuine inner tensions and mental fears to be explored. So I report it was with immense pleasure and relief that in 1971, when I returned to the lap of the Bureau to direct THE FBI in their seventh season, I read A SECOND LIFE.

Did you hear Tom Barbour’s line, “Hey Ralph, … got any ice?” There was no dialogue scripted there. That was strictly ad lib: a director making a television miniaturized Hitchcockian nonappearance.

I never met author Dick Nelson, although I directed two of his THE FBI scripts that year. Like the teleplay authors of ROUTE 66, he shaped this script so definitively for a specific location, the Sausalito houseboat area, that there was no possible recourse except to take the company north to the Bay area for filming. And that’s what was done, but rather than going on location for a single production, two films were scheduled to shoot. The first would be filmed in Santa Rosa. It was planned that I would join the company there and would film my first two days in Santa Rosa, move south to the Bay area for four days of filming and finally would return to the Warner Bros. Studio in Burbank for a final day of interiors on a soundstage. All of those plans were laid out long before I reported.

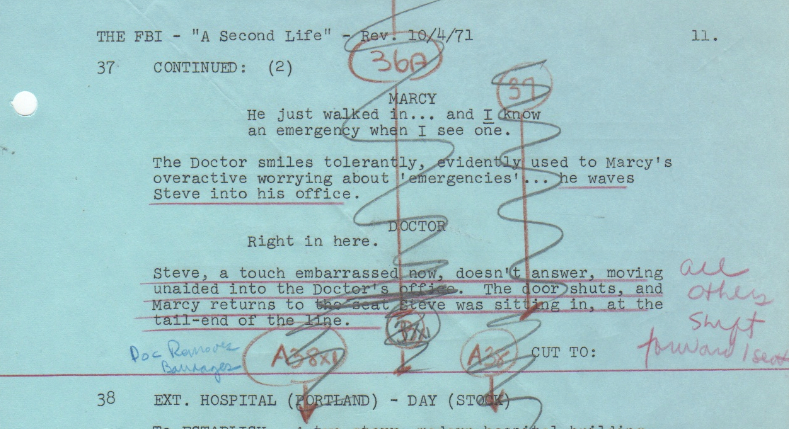

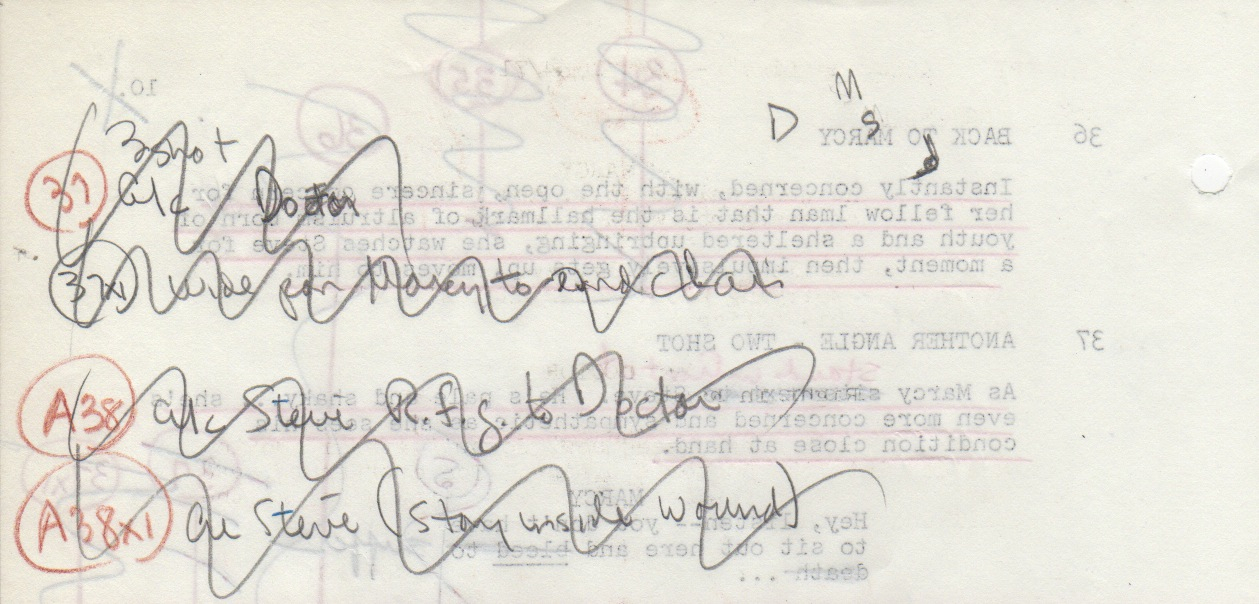

I always figured it was a director’s prerogative to add, as long as dialogue wasn’t changed, whatever was needed to enhance a sequence. The clinic scene as scripted ended with Marcy taking her seat at the tail end of the line.

I felt the scene was incomplete; it was ending factually, not emotionally. I thought the most important factor in our story at this point was Steve and his wound. That needed to be the focus for the ending of the scene. I was filming in a real clinic. I had a treatment room and an actor playing the doctor. All I needed was some bandages, so I ordered them, and with just two simple shots (A38 and A38X1) I was able to end the scene keeping the focus on Steve.

And I had the actor I wanted from my first reading of the script to play him. Eight years earlier in 1963 I saw Martin Sheen for the first time when he guest starred on an episode of THE DEFENDERS. I was blown away by his performance. I was directing one of the snake eyes I mentioned, and needed a young actor for a one-day role. Lynn Stalmaster, who was casting, suggested Martin. My response was I didn’t think he would accept such a minor role; his appearance on THE DEFENDERS had been a lead. Lynn told me Martin was new on the west coast and wanted to work, and so he was hired. Seven years later in 1970 I was directing CRY OF TERROR, an episode of INSIGHT, and I suggested Martin for the leading role of a South American revolutionary. Jane Murray, who was casting, felt Martin was not Latin enough, and so we cast Peter Mark Richman. It wasn’t until later that I learned Martin’s real name was Estevez. I did cast him in the INSIGHT I directed the following week and two more times that year. The second time was kind of a replay of our first encounter. I was directing BULLET FOR A HERO on DAN AUIGUST. We had cast Monte Markham and Laurence Luckinbill as two of our guest stars, when the casting director suggested Martin for the third and least important of the male roles. Again I said I didn’t think the role was important enough for him to play, and again I was told, “He wants to work,” and so again he was hired.

In Dick Nelson’s script Lee Thompson’s Oregon scenes were set at a Dock and interiors of his home. Production had decided that we would film all of those scenes on our first day in Santa Rosa, and the Dock scenes were changed to his patio.

There was a sequence involving a hospital and a nearby riverbed, and the production people found a location in Santa Rosa that fulfilled that requirement. Once it was decided to film those scenes there, more work was needed to round out the day’s work. A used car lot, which could have been found in the East Baby area, became the choice to complete the second day’s schedule.

Another major plus for me on this production was that William Spencer was back on the series as director of photography. This was the first time I got to work with him since he had left THE FBI mid the series’ second season to photograph Quinn’s feature film, THE MEPHISTO WALTZ. As always he was meticulous as he painted with light. The night scene in Thompson’s study was a case in point. We filmed it during the day, when light still shined through the drapes on the windows. Billy had the windows blacked out on the outside with dark material, and again as with all location filming he was lighting with all of his instruments on the floor.

At one point Marcy asked Steve something, and he replied, “Huh?” In the shows I worked with Martin before this, I became aware that Martin, under circumstances like that would reply, “Say again.” And that’s what he said in the scene. I mention this because I know that I have copied that from Martin. To this day if I do not understand what someone says to me, I don’t ask, “What did you say?” I do a Martin Sheenism and say, “Say again.”

Martin was not the only casting choice I made when I read the script for the first time. I had worked with Meg Foster the year before when she played a blind girl (with those wonderful very pale blue eyes) in an episode of THE INTERNS, and again when she played an angry drunk on BULLET FOR A HERO on DAN AUGUST. I knew immediately that she was the one I wanted to play Marcy. Since DAN AUGUST had been a Quinn Martin production and Meg had the season before appeared in an episode of THE FBI, she was quickly approved, and a script with an offer was sent to her agent. Imagine my disappointment when an immediate reply came back from the agent that she would have to turn down the offer. She was very pregnant and expecting the arrival soon. So casting and I went back to work. We plowed through the Academy Player’s Directory and prepared lists of possible replacements, when Meg’s agent called again. He told us Meg had delivered a healthy little boy, that she was very eager to accept the offer to play Marcy, but there was one request: could she bring the baby to the location, and would we be able to schedule her filming so that she would be able to nurse her newborn. That was a no-brainer! I had my two co-stars.

The ground floor hospital entrance, the stairwell, the rear of the hospital and the riverbed were filmed in Santa Rose the second day. The second floor hospital corridors and the Commissioner’s hospital room were filmed the last day back at the studio in Burbank.

Sometimes when actors make mistakes with their dialogue, the results end up on one of the famous blooper reels that eventually find their way to an airing on You Tube. But many more times good actors stay in character and incorporate the mistake in dialogue into the scene. As scripted Martin was supposed to say: “Yeah – I’ll start asking around about an — Obstetrician.”

Instead he said, “Yeah, you know what – yeah I’m going to ask around town – I’m gong to find out who the – who the best – uh — pediatrician is – you know …”

Meg giggled and said, “You mean obstetrician?”

Martin without missing a beat said, “Obstetrician, right.”

… and they continued with the rest of the scene. I thought it was charming.

I don’t remember if Meg knew how to work the pottery wheel or whether she learned on the job, but that was so typical of what is required of actors. Beulah Bondi told me that when she was hired for the feature film, SO DEAR TO MY HEART (and I’m sure I’m citing the correct film) she read in the script that there were scenes where she would be weaving on a loom. Being Beulah she immediately requested that the studio send a loom to her home and someone to instruct her, so that she could learn and practice. And practice she did until she was very proficient. Came the day of filming those scenes, and well-prepared Beulah found out the director had no plans to utilize her newly developed talent.

Quinn Martin had been a sound editor before he rose to the rank of producer. He was an absolute fanatic about sound overlaps when scenes were covered in close-ups. To avoid overlaps, the actor off camera had to stop talking before the actor on camera said his lines. When filming an emotional scene like this last one between Martin and Meg, I always filmed over-the-shoulder shots in preference to close-ups. As long as both actors were on camera, they could speak over each other’s lines like people do in real life.

For our one-page scene at an airport, we went to nearby Oakland. The scene was scripted to occur at an Exterior Gate. We saved time and labor without making any artistic compromise by filming at the main entrance into the airport.

There were some panning shots needed of cars in transit and some sequences with the camera filming actors in the moving car. They never seemed to be filmed at the times they were scheduled. The previous scene with Zimbalist and Reynolds was scheduled at the end of the second day as the company was moving from Santa Rosa to San Francisco, but the scenes in the hospital that day, the stair well, the hospital exteriors, the river bed, the used car lot and one of Martin Sheen’s phone booth calls took up enough time that with the earlier loss of light in October, that sequence was rescheduled to “when possible.” As I remember, we filmed it later as the company was making one of its moves – probably the move to the Oakland airport.

My cousin Carol, who lives in Berkeley, visited me last week as I was preparing to start writing this current post. Carol likes to watch with me shows I directed. She asked if we could view A SECOND LIFE. I had forgotten that Carole visited the set in Sausalito in 1971, when I was filming. She was there the day we filmed the epilog, the scene you’re about to see. She told me it was exciting, even though she couldn’t see what we were doing, because the scene we were filming was the one with Martin and Meg buried in the back of the ambulance.

Philip Saltzman had replaced Charles Larson as producer. According to the Internet Movie Data Base, this was his third season at the helm. I had not known Phil earlier, although I had directed DETOUR ON A ROAD GOING NOWHERE on THE FUGITIVE for which he was credited with creating the story. Phil was different than any of the other producers I had worked with on QM productions. He wanted to be responsible for more than just the scripts. He wanted to be involved in all aspects of producing. I admired that. Phil told me that after one of the screenings of the dailies for A SECOND LIFE, Quinn had complimented him. Quinn thought it remarkable that in a series’ seventh season, Phil was turning out shows like A SECOND LIFE and earlier shows that season like GAME OF TERROR and END OF A HERO. Phil smiled at me as he pointed out (as if I didn’t know) they were all productions I had directed.

I’ve assumed exterior scenes for “The F.B.I.” was usually filmed in and around the Los Angeles area. Were there any production issues when it came to filming on location in the S.F. Bay area and then flying back to Hollywood for studio shots. Logistically, it sounded like it was challenging, but, as with many productions split between Hollywood and anywhere outside of the L.A. area, not unusual.

The flight from San Francisco to Los Angeles took just a bit over an hour. We wrapped in SF Tuesday, flew back to LA that evening and reported to the studio the following morning for the seventh and final day of filming.

Mr Senensky,

Very enjoyable post. Ever since I saw him in a first season episode of Route 66, up until today, no matter how small or large the part, Martin Sheen has always given very nuanced and “real” performances…….a great talent.

Talk about ‘The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight’ – the feared ‘Syndicate’ went 0-for-3 in “hitting”…oh brother. The first attempt was particularly amateurish. But, I will forgive all because you, the writer, and the actors nailed the money shot in the 13th video – the ambulance scene. When Martin started saying, “don’t do this, don’t do that”, I knew Meg would start tearing up, and sure enough, she did.

Until I checked out your ‘Dan August’ eps., I never heard of Meg Foster before…fortunately, there’s enough video online from her other projects to see what I missed. Most shocking is a tidbit in IMDB about her getting canned from ‘Cagney & Lacey’ for not being feminine enough. Say what!!?? Were they blind or crazy?! I never watched that series, so this was news to me.

Luckily, I spotted a book in the library about ‘C & L’, written by Julie D’Acci. Very brief history re Meg: The 1981 TV movie had Loretta Swit in the Cagney role. Swit was still doing ‘M*A*S*H’, so ‘C & L’ co-creator Barbara Avedon conducted script readings for a replacement on the new series. She gave the job to Meg, saying her reading was “head and shoulders above” the other candidates. Immediately afterward, a CBS suit took Barbara aside and clobbered the choice (“she’s trouble, she’s a dyke, she can’t carry a series”). The book also quoted Meg from an earlier magazine article saying her favorite ROLE was as a lesbian in a 1975 movie. Is this how an executive puts two and two together on the suitability of an ACTOR? Pretty pathetic.

‘C & L’ ran for six eps. as a Spring replacement in 1982. I just watched ep. #6 on HULU and saw nothing wrong with Meg’s performance. As I understand it, the character was first written as a tough chick, so that’s how it was played. CBS would not renew the series in the Fall unless certain conditions were met…dumping Meg was one of them. Perhaps more important: the writers “softened” Cagney.

Of course, the recent passing of “Zimmy” was big news. I also read that long-time Q.M. Asst. Director Paul Wurtzel passed away on April 18.

First off, I did not know about Paul Wurtzel’s passing. We not only worked together a lot, he lived just a half a block from me on Sunset Plaza Drive.

I knew about Meg and CAGNEY AND LACEY. I remember the “suit” from CBS who aired the accusation. She and Diana Muldaur were my two favorite actresses to work with.

Mr Senensky,

I don’t know if you remember me but I had posted a comment a few months ago on your posts on a Rookie episode that you directed guest-starring Martin Sheen, an actor of which I am a really big fan. I just wanted to thank you again for all the videos and insights of shooting with Mr Sheen that I have found on your site. Some episodes of series he starred in, as this one of the FBI, are really pretty hard to find so I am always glad to see them and to read trivia about it. And I have been just looking at them one more time to celebrate Mr Sheen’s 75th birthday on today. Just love the Martin Sheenism “Say again”, sometimes I like to use it too in conversation now 🙂

There is a cute Martin Sheen story from when he filmed “Gettysburg,” in Gettysburg PA. He wasn’t particularly shy around the set or the locals (there were hundreds) who worked on the film. The main cast had houses rented for them and at the end of one day, Sheen was driving back to his house when he spotted a kid who had been on the shoot that day walking home. So Sheen picked him up and delivered him at his home. Imagine shocked Mother’s reaction at the star of the picture giving her son a ride home.

She was shocked and surprised. I’m not!